IN THE SHADOW OF THE SPIRE

In which answers are demanded, justice is served, and a young boy is unexpectedly disappointed by lost memories…

Decipher Script is possibly my favorite skill.

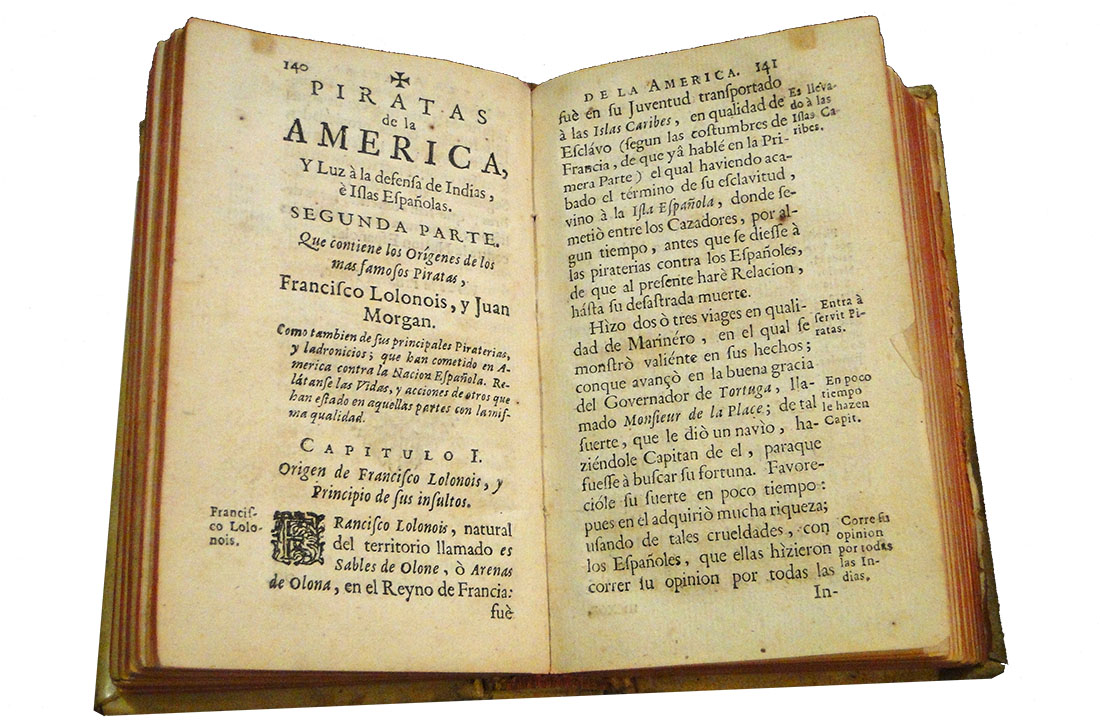

Tussling meaning out of antediluvian texts and puzzling out the secrets of strange runes is awesome. On the one hand, there’s that Indiana Jones thrill of plucking lost truths from ancient texts (towards which end I commonly stock my fantasy setting with hidden epochs and unknown historical ages which are clearly defined but not commonly known, presenting a meta-mystery which the PCs can slowly unravel — although that’s a topic for another time). On the other hand, encrypting a text is also a great way of signaling that there’s something of particular importance to be found (much like locking or trapping a chest). And on the gripping hand, when only partial successes are achieved (or the text is fragmentary to begin with) the cryptic passages immediately create an air of enigma.

With that being said, Decipher Script is also one of the most problematic skills because:

(a) A lot of GMs don’t want to risk their previous railroads being derailed when someone fails to decrypt a text or cypher, so they don’t include opportunities for using Decipher Script.

(b) The default use of the skill is rendered completely obsolete by a 1st level spell (comprehend languages).

You solve the first problem, obviously, by realizing that failing to decipher the counter-ritual that would thwart the cultists is exciting because it forces the PCs to find a different solution to their dilemma. (And then following up by liberally strewing your campaign world with enigmatic texts because… well, why wouldn’t you?)

The second is a bit trickier to deal with. You could resolve it with a house rule by turning comprehend languages into a spell that grants a hefty bonus to your Decipher Script check instead of simply rendering it irrelevant; or by modifying secret page so that it can thwart comprehend languages but not mundane deciphering attempts. But over the years I’ve opted to implement a variety of other methods instead.

LAYERED CIPHER

One technique can be found in this week’s campaign journal: When Ranthir casts comprehend languages on the encoded journal, it doesn’t work. This is because the journal has been encoded with a Decipher Script check used in conjunction with a comprehend languages spell. (The idea being that you lay the memetic weave of the spell over the page and then inscribe the encoded text onto the page through the weave. When the weave is withdrawn, the text becomes even further “scrambled” and restoring the memetic weave — with a fresh casting of comprehend languages — only gets you back to the encoded text.)

ENCODING A LAYERED CIPHER: This requires a conjoined Spellcraft check (DC 20) and a Decipher Script check (DC 20). If both checks are successful, the text is successfully encoded with the layered cypher. If the Spellcraft check fails, you end up with a text of irrecoverable gibberish. If the Decipher Script check fails, a comprehend languages spell will reveal the text normally.

DECODING A LAYERED CIPHER: A layered cypher can still be decoded with a simple Decipher Script check, but the DC for doing so is at +20. Alternatively, if you cast a comprehend languages spell first, you can use a Decipher Script against the normal DC of the cypher.

IDENTIFYING A LAYERED CIPHER: A successful Decipher Script or Spellcraft check (DC 25, or DC 10 if currently using a comprehend languages spell) can identify the layered cypher for what it is.

LONG TEXTS

Another way of rewarding the Decipher Script skill over the comprehend languages spell is through the simple expedient of using longer texts: The comprehend languages spell only lasts 10 minutes per level. That’s plenty of time to read a couple of pages, but if you’re looking at an archaic tome containing several hundred pages it will take you hours to read through it. You can either cast the spell multiple times, or just make a single Decipher Script check.

Alternatively, for long texts which are heavily encoded or badly damaged complex skill checks (X successes before Y failures) are a great mechanic, allowing the character to suss out additional details for every hour of study with a successful check.

OTHER USES OF DECIPHER SCRIPT

CREATE CIPHER: You can create a cipher to encode written messages. The DC for deciphering the cipher after its creation is equal to 10 + your total skill modifier at the time of the cipher’s creation. Creating a cipher takes 1 day of uninterrupted work.

Quick Ciphers: You can put together a quick cipher in 1 hour, but the DC for breaking the cipher suffers a -5 penalty. A cipher can be created in 1 minute, but the DC for breaking the cipher suffers a -20 penalty.

DECIPHER SPOKEN LANGUAGE: You can make a Decipher Script check at a -10 penalty to decipher a spoken language and communicate in a pidgin fashion. You must make a check for each idea or concept you attempt to communicate or decipher. (You can try this check again if the creature you’re trying to understand repeats themselves or if you try to make yourself understood again.)

(I also allow people to invest ranks into their Language skills, and then use this same mechanic to communicate with people in related languages. This, of course, requires the extra prep of designing actual language trees for the languages of your world. The invested Language skill can also be used like Craft or Profession in order to create written material for sale.)

INTERCEPT SIGNALS: While observing enemies, you can catch a view of any visual signals they are using to coordinate their actions. You can attempt to puzzle out the meaning of the signals and determine the enemy’s short-term plans. Such signal systems tend to use many false signals, leaving a chance that you will pick up on a fake set of signals or misinterpret a signal (if you fail your check by 5 or more). Once a character has cracked a signal set, it becomes much easier to subsequently decode it: The character gains a +5 competence bonus to decode subsequent uses of that signal set.