The trickiest part of finding an audio book is that it has to be both a good book AND have a good narrator. What I’ve discovered is that it’s much easier to find a narrator you like and browse the corpus of books they’ve done looking for other titles that look appealing than it is to look for appealing titles and then just hoping that the narrator will be good.

The trickiest part of finding an audio book is that it has to be both a good book AND have a good narrator. What I’ve discovered is that it’s much easier to find a narrator you like and browse the corpus of books they’ve done looking for other titles that look appealing than it is to look for appealing titles and then just hoping that the narrator will be good.

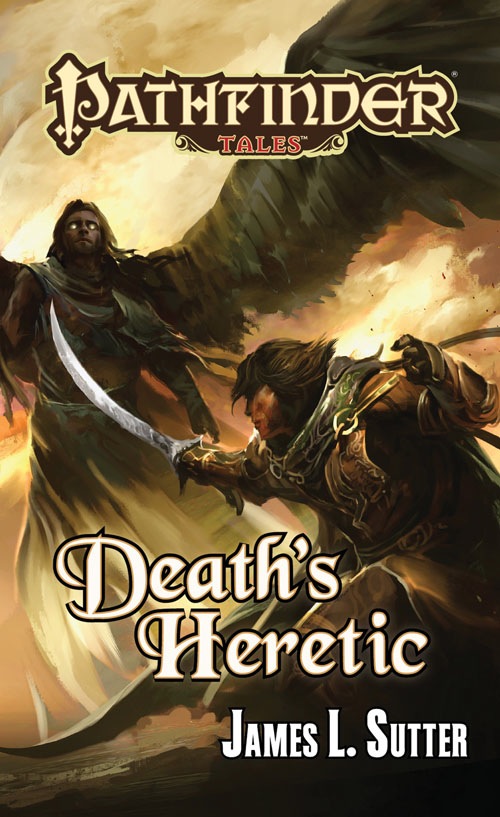

Enter Ray Porter, who consistently elevates everything he’s involved with. (I’ve previously listened to his presentations of Dennis E. Taylor’s Bobiverse and Peter Clines’ Threshold series among others.) I’m browsing through the literally hundreds of audio books he’s recorded when I suddenly discover that I already own one of the books he’s done: A Pathfinder Tales tie-in novel called Death’s Heretic by James L. Sutter.

Truth be told, I’m not entirely sure how I acquired it. It must have been part of a bundle or a free book-of-the-day deal or something. But, in any case, it had been sitting in my Audible library untouched for several years at this point.

And that’s a pity. Because this book is really good.

HIGH FANTASY NOIR

In form, Death’s Heretic is a noir detective story in a fantasy setting.

Over the years, I’ve read any number of such stories. Often they have a steampunk veneer. Many of them take place in crapsack worlds. But a lot of them are just literally Dashiell Hammett or Raymond Chandler with a veneer of magic and a smattering of fairy wings lightly dusted over the affair.

Death’s Heretic, on the other hand, stands out from the pack by truly owning its identity as a D&D… err, sorry… Pathfinder novel. Rather than trying to limit its scope to some “noir” subset of Pathfinder, it instead embraces the totality of Pathfinder’s cosmology and interprets it through the lens of a noir story.

Let me see if I can explain the difference: Whereas a typical “D&D noir” novel would open with a dame walking into a detective’s office and saying that her dad was killed by a fireball spell, Death’s Heretic opens with an angelic representative of the Goddess of Death requesting assistance because someone was killed and, when they attempted to resurrect them, they discovered that their soul had been kidnapped from the afterlife.

There’s also a dame, but you can see the difference. It’s not just that there are more fantasy elements being thrown into the mix; it’s that the fantasy elements are being allowed to fundamentally alter the nature of the story. It’s one thing to set a noir story in a weird, selective version of Waterdeep that somehow ends up looking like 1930s San Francisco with the serial numbers filed off, and it’s another to take the totality of Waterdeep, frame a story there, and truly see where it takes you.

Sutter pushes the envelope in other ways, too: He actually divorces himself quite strongly from noir tropes in general by setting the story not in some fog-drenched metropolis, but rather in the sun-drenched empire of Thuvia. Strong elements of pulp fantasy are also naturally pulled in as part of the setting. And that’s just the beginning, as Sutter relentlessly cranks up the dial as the narrative progresses.

BUT ALSO…

Death’s Heretic has more going for it than just novelty and creativity, though. Sutter just writes a legitimately good novel: The characters are interesting and multidimensional. He takes the time to weave together a number of interesting themes revolving around mortality, immortality, and the nature of faith.

Ultimately, this is one of those reviews I write specifically to call attention to something really nifty that I think is (a) not well-known enough and (b) that people would really enjoy if they knew it existed.

So now you know.

I hope you have a great time with it.

GRADE: B-