Before we proceed, I want to talk a little about my assumptions here: By default, the process of advancing a tier means that you gain +4 stat points, +1 to an Edge of your choice, +1 Effort, and a skill. (You’ll also pick up extra abilities from your character’s Type, but we’re not going to worry about that for the moment.) For the purpose of these discussions, however, I’m not going to be looking at characters who have dumped all their advancements into becoming hyper-specialized at doing one thing.

Before we proceed, I want to talk a little about my assumptions here: By default, the process of advancing a tier means that you gain +4 stat points, +1 to an Edge of your choice, +1 Effort, and a skill. (You’ll also pick up extra abilities from your character’s Type, but we’re not going to worry about that for the moment.) For the purpose of these discussions, however, I’m not going to be looking at characters who have dumped all their advancements into becoming hyper-specialized at doing one thing.

For example, I’m going to assume that characters are spreading their Edge boosts around instead of concentrating them all in a single stat. (In practice, I’ll be assuming that your highest Edge will be 1 + ½ your Tier.)

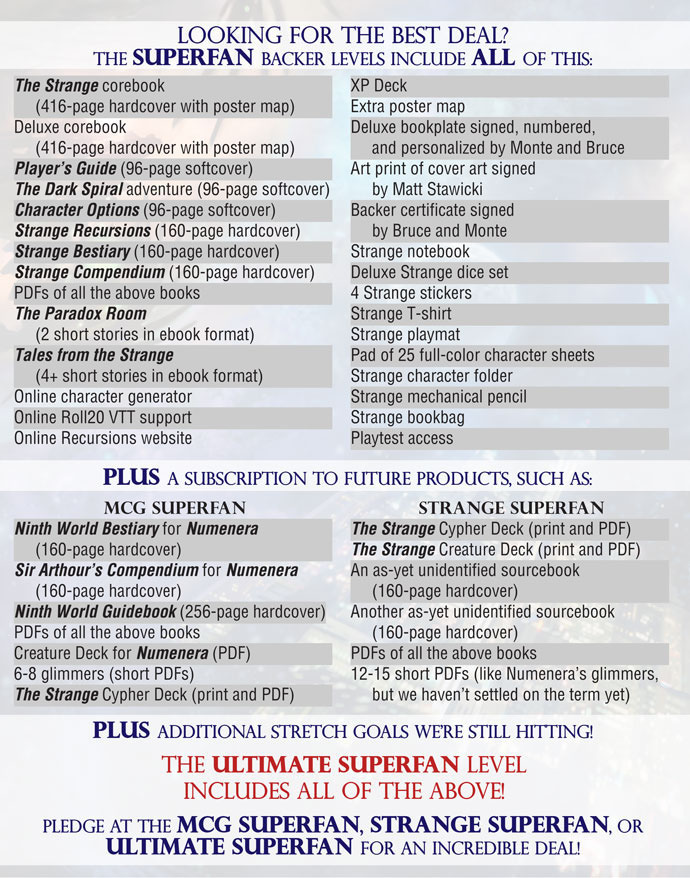

For the purposes of analyzing what characters are really capable of, I’m also going to be bumping up the descriptions of tasks with difficulties of 8+ (for the reasons that I described in Part 1). In practice, we’ll be looking at something like this:

| 7 | Impossible without great skill or great effort |

| 8 | Impossible without great skill or exceptional effort |

| 9 | A task worthy of tales told for years to come |

| 10 | A task performed by those who become legends in their own time |

| 11 | A task worthy of legends that last for lifetimes |

| 12 | A task that normal humans couldn't consider under any circumstances |

(Difficulty 12 is the significant breakpoint here because a person with specialization, the best circumstances in the world, and willing to expend a single level of Effort still couldn’t possibly succeed.)

TIER 1 vs. TIER 3

Our general discussion has gone a long way towards establishing our baseline expectations for a Tier 1 character: They’ve got Edge 1 in one or two ability scores and they’ve got one level of Effort. If we imagined a “Tier 0” character who lacked any Edge or Effort, the Tier 1 guy can last a little longer and can also accomplish things that are a little bit tougher. We might think of him as being just a little bit better than a normal Joe, but the types of things he would consider “normal” or “routine” haven’t really shifted.

Now, let’s compare that starting character with a character who has achieved Tier 3: They’ve got Effort 3 and their high Edge is 3. They’ve probably also picked up at least one specialization.

The upper limit for this character in general has now become Difficulty 9: “A task worthy of tales told for years to come.” They don’t have to be skilled at it; they don’t need a great set of tools or perfect circumstances. They just focus their Effort on it and they’ll do stuff that people in the local aldeia will still be talking about a decade from now.

In their area of specialization, however, things are obviously even better: Without expending any effort at all, they can achieve things normal people would consider impossible (difficulty 8). Even under the worst conditions (+2 difficulty), they’re still capable of accomplishing stuff that average people would find intimidating under normal conditions.

And their absolute upper limit is even better: Specialization (-2), effort (-3), and a couple of assets (-2) means that they’re already capable of accomplishing difficulty 13 tasks… they’ve already blown the cap off our difficulty scale.

What type of stuff can they succeed at 50% of the time? Well, in general they can succeed at Intimidating tasks (stuff normal people almost never succeed at) 50% of the time by expending effort. If they’re specialized and have favorable conditions, they can achieve the impossible 50% of the time.

Notably, however, the stuff they consider routine doesn’t accelerate as quickly: Instead of just the stuff average people consider routine (difficulty 0 tasks), they also consider stuff people consider simple (difficulty 1 tasks) routine. Perhaps more telling, the “standard” difficulty of the game is now routine for them.

Okay, let’s use our touchstones: Even if these characters aren’t specifically trained at a task, they are capable of crafting any numenera item in the game; they can climb across smooth ceilings; and they are likely to possess knowledge very few people possess. If it’s their specialty, then they possess “completely lost knowledge” and they can do whatever the equivalent of climbing a wall of glass without any equipment is.

TIER 3 vs. TIER 6

So what we’ve rapidly established is that the small numbers of the Numenera system rapidly accumulate huge shifts in power and ability.

A Tier 3 character can generally perform the seemingly impossible and will, in their specialty, be capable of feats that will literally make them legends.

Because that top end already strains our ability to really comprehend what they’re capable of, the big conceptual shift between Tier 3 and Tier 6 is in the routine: With Edge 4 in their specialty, tasks of standard difficulty have become routine. More notably, that which normal people consider difficult they automatically consider simple.

(Pause and think about that for a moment: Think about the stuff that you find really difficult to do. The stuff that gives you a sense of satisfaction when you complete them successfully. Tier 6 characters consider that stuff trivial.)

The other end of the scale becomes simply staggering: Effort 6 expands their general range of ability (without skill or favorable circumstance) to difficulty 12 tasks; i.e., stuff that normal humans couldn’t even consider doing. Combine that with specialization (-2) and favorable circumstances (-2) and you’re up at difficulty 16… which is just completely off the human scale.

How far off the human scale? Well, the difference between “task worthy of legends that last for lifetimes” and what these characters are able to achieve in their specialization is the difference between a task the “most people can do most of the time” and “normal people almost never succeed”. (If there was a world where every high school basketball player had the skills of Michael Jordan, these guys would be the Michael Jordans of that world.)

Our touchstones have already been rendered largely useless, but consider this: Tier 6 characters who are not specifically skilled in climbing are nevertheless capable of expending a little effort and climbing featureless glass walls 45% of the time.

In an area of specialization (-2) they’ll have a 15% chance of knowing a piece of completely forgotten knowledge without spending any pool points. If they expend maximum effort, their chance of knowing something which (I must repeat) is completely forgotten rises to a mind-boggling 70%.

CONCLUSIONS

My big take-away from this is that by the point you reach Tier 6, Numenera is no longer a game about characters wandering through inexplicable technological ruins that they are incapable of understanding. The characters are capable of easily creating original pieces of numenera to rival even the most powerful technology of the Ancients and they almost certainly understand many of the deepest mysteries of the cosmos they inhabit.

(And if you’re still looking for a way to calibrate your understanding of the highest tiers, consider this: If a Tier 6 character was actually hyper-focused with Edge 6 (+3), a specialized skill (+2), proper tools (+1), and favorable circumstances (+1) they would consider even tasks that normal people consider “impossible without skill or great effort” to be routine.)

It looks to me like the turning point probably comes somewhere around Tier 4: Tier 1 you’re slightly better than the average person. Tier 2 you’re a highly talented expert (or Big Damn Hero depending on your perspective). Tier 3 is where you hit Legendary status. Tier 4 is where I think you have to start looking at a phase change in the types of stories your characters are getting involved with unless you want to suffer a dissonance with what the mechanics are telling you.

One notable thing to keep in mind, though: Although Numenera rapidly expands the high-end of potential, the low-end of surety doesn’t expand as quickly. The PCs may become incredibly potent demigods by the standards of their age; but they also remain distinctly mortal ones.