A couple days ago, in response to Numenera: The Aldeia Approach, Tomas mentioned that he was “still trying to find the right way to describe Numenera” to new and prospective players. This can be tricky, particularly if your players aren’t familiar with the source material Monte Cook is drawing inspiration from. (If you can only read one thing to grok Numenera, I recommend The Book of the New Sun by Gene Wolfe.)

My approach is to try to let the players appreciate how utterly incomprehensible the gulf between our world and the Ninth World is. That fundamental, existential mystery – that the history of the world is beyond human understanding, and yet that history inexorably shapes every facet of the world in which their characters live – is, in my opinion, the heart of what makes Numenera special.

So I structure my introduction to the Ninth World around five bullet points.

FIRST

The Ninth World exists one billion years in the future. Between now and then there have been eight mega-civilizations. These mega-civilizations are literally beyond our understanding. Our life here in the 21st century isn’t a mega-civilization; it’s barely a precursor to one of them. And the people of the Ninth World know very little about them as well. We know that one of them mastered time travel; another ruled over a galactic empire; another explored a multiverse of different dimensions. We also know that at least one of them wasn’t human and that, in fact, for a time there were no humans on Earth at all. (We also don’t know how or why humans came back.)

SECOND

To get some sense of what the mega-civilizations were like, look at the Clock of Kala. (At this point I’ll point at the map: I printed out a large, poster-size version of the map on vinyl. I either hang it on the wall or roll it out on the table, depending on the venue. But you can just as easily open the book and point.) It’s a massive, perfectly circular plateau several thousand miles across. Vast features of the landscape (on a scale larger than the tallest mountain) are utterly artificial extrusions from the dim recesses of a forgotten prehistory.

THIRD

But the Clock of Kala is nothing but a toy to these mega-civilizations. To give some sense of what they were capable of, consider that the planet Mercury is gone. The people of the Ninth World don’t miss it because they never knew it existed, but at some point in the past the entire planet was plucked from its orbit and they did something with it. What? We don’t know.

FOURTH

But the touch of the mega-civilizations can also be seen at the other end of the scale: Even the dirt beneath our feet is, in fact, artificial – particles of plastic and metal and biotechnical growths which have been eroded by incomprehensible aeons; each bucket of soil filled not with stone arrowheads, but with compact power supplies and the cracked crystals of ancient data storage devices.

FIFTH

Our game begins in the Steadfast. You can think of the Steadfast as a Renaissance civilization. But instead of rediscovering the technology of Ancient Greece and Rome, the Steadfast is rediscovering the technology of these mega-civilizations. This technology is known as numenera, which mechanically take the form of cyphers (items which can generally be used once) and artifacts (items which can be used repeatedly before breaking down). It should be understood that most of the time it can be assumed that people are NOT using these items the way they were originally intended; their original purposes are often completely enigmatical. But we can do the equivalent of finding a CD and using it as a mirror; or finding a cellphone and using its screen as a flashlight.

From here you should be able to pivot to a pertinent discussion of whatever location or other campaign frame you’re planning to use, whether that’s the Wandering Walk or an aldeia or something even more esoteric.

HOW MUCH WEIRD TO PUT IN THE GAME?

The ineffable mystery of the Ninth World’s history, unfortunately, seems to create some barriers in itself. The minute you quantify something or define its precise outline, the mystery ends and that which was engagingly enigmatic instead becomes pedestrian. The rulebook thus frequently emphasizes how important it is that the GM never allow the players to box the setting in like that.

Some have interpreted this advice to mean that the GM should just make everything random and inexplicable (which they naturally find frustrating). But that’s not the point. The point is that no matter how much you figure out, there will remain more that you don’t. This doesn’t render exploration or investigation pointless or without reward, any more than the fact that real world scientists haven’t completely solved the Grand Unified Theory makes the work of Newton or Galileo or Einstein pointless or without value.

There’s a Lovecraftian aspect here: The world (and the past epochs of the mega-civilizations) are fundamentally not comprehensible by mere humanity; and if we were to do what was necessary for us to truly understand them, we would no longer truly be human.

So how much weirdness should you, as the GM, put in the game? Too much and the game turns into random ramblings. Too little, though, and you end up with something pedestrian; something lack the essential spark that makes Numenera special.

The first thing to understand, perhaps, is that the amount of weird will vary by circumstance. There’ll be places with very little weird. And there will be places which are through the looking glass. That internal contrast is essential, actually, because it allows the “weird” to define itself.

With that being said, if you find yourself creating something for Numenera that feels a little too normal – something that you could just as easily find in a game of D&D or Star Wars or vanilla Traveller – take a moment to step back and figure out how to add at least a little dash of the weird. Take at least one aspect of it and think about how you can twist it; how the influence of the numenera could transform it.

The Aldeia Approach is actually a specific example of how you can do this: Basically you take a typical Renaissance village, add one piece of numenera, and ask yourself, “How does that change everything?” As you’re getting up to speed with the Ninth World, that kind of showcasing of a single weird aspect of the setting will take you a long way.

RUNNING WITH NUMENERA

I’m also asked with a surprising frequency why I spend so much time talking about Numenera here on the Alexandrian. As with most of the RPG-related stuff you’ll find posted here, it’s a reflection of what I’m actually running and playing at the table. I’m at 40+ sessions of Numenera and, honestly, my players just keep screaming for more. I literally can’t run it often enough to keep up with the demand.

So as long as we’re discussing how to introduce the game to new players, let me also talk about why, once you start, Numenera is a game you’re going to keep playing for a long time to come:

Simple Prep. Everything in the game basically boils down to assigning it a level. It literally can’t get any easier than that. But the great thing is that the system allows you to selectively do more detailed prep whenever you feel it’s necessary by assigning things additional levels specific to certain tasks or abilities. This sort of fractal complexity, where the game only becomes more mechanically complicated when you think the cost is worth the reward, is incredibly effective. You never feel unnecessarily bogged down by the rules; you also never feel limited by them.

Simple Prep. Everything in the game basically boils down to assigning it a level. It literally can’t get any easier than that. But the great thing is that the system allows you to selectively do more detailed prep whenever you feel it’s necessary by assigning things additional levels specific to certain tasks or abilities. This sort of fractal complexity, where the game only becomes more mechanically complicated when you think the cost is worth the reward, is incredibly effective. You never feel unnecessarily bogged down by the rules; you also never feel limited by them.

Creative Lubricant. The entire system is designed around some simple mechanisms which encourage the GM and players to take creative chances. GM intrusions for example provide a safety net that allows the GM to take really big chances because the players have a streamlined mechanism for telling the GM that they’ve gone too far. Major and Minor Effects also get the players thinking creatively outside of the box.

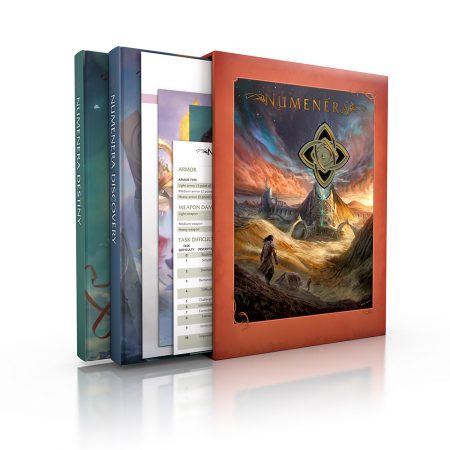

Tremendous Support. The Numenera product line is phenomenal. There’s fantastic setting material, a multitude of scenarios, fabulous bestiaries, and even more amazing stuff on the way. (My prep for Numenera often consists of just flipping through one of the bestiaries and saying, “I wonder what will happen when they see one of those things?”)

The game also features a large dynamic range when it comes to PC abilities, which allows the game to shift its focus and content over the course of a campaign (which helps to keep things fresh). And I’m very much expecting this to become even more true with the greater emphasis being placed on PCs getting involved in managing communities, building organizations, and the like in the upcoming second edition of the game.

FURTHER READING

Numenera – System Cheat Sheet

Numenera: Calibrating Your Expectations

The Art of GM Intrusions

The Aldeia Approach

Fractal NPCs

I liked your “Aldeia Approach” because it helps solve (what was for me) the opposite problem: Numenera wasn’t weird *enough*.

When I heard about an RPG based on Vance’s DYING EARTH and Gene Wolfe’s BOOK OF THE NEW SUN, I was really excited. But I found the genre tropes of the finished product a little too similar to D&D.

For me, a central trope of dying earth fiction is that every chunk of the world is vastly different from every other chunk. Every town Cugel passes through is radically different from the town before or the town after – in inhabitants, in customs, in technological / magical capabilities, in economy, in everything. The empire Severian travels through is so diverse that not everyone recognizes him as a torturer, and many people he meets don’t even know the torturers exist.

Compare this to the Steadfast, where (for instance) Aeon Priests are widely enough known that PCs can expect to find them regularly. That rubbed me the wrong way. I know that an RPG setting needs to give GMs some material to sink their teeth into, so maybe there’s not an easy way out of it.

Anyway, your Aldeia Approach is the best way to develop that feel of alien diversity that I’ve seen. So thank you!

Thanks for these series of articles. I always appreciate your insight into this game!

One thing you said that I want to touch on: I don’t think Lovecraftian ideas work with Numenera. I understand that your point was likening two unknowable and incomprehensible histories underlying the world of the characters. But there is a fundamental difference between the two. When a character (in story or game) sees a small part of the Lovecraft mythos they are harmed by it; whereas in Numenera finding out those small parts strengthens characters.

I first hit on this with the In Strange Eons Glimmer. I tried to use some Lovecraft ideas into my game, and it didn’t work. And it’s because of that distinction. In Call of Cthulhu you are playing a game of depletion, in which your character is struggling against the Mythos and has to choose how far they will go and how much they will endure to fight against an utterly hostile universe. Knowledge is dangerous and treacherous. In Numenera, your character is struggling to learn as much as possible, and discovery and understanding is not only rewarded but the primary way in which you earn XP. Numenera characters are strengthened by discovery, and knowledge is the currency of the game.

@John P.: Speaking of Aeon Priests (and this begins to be a departure from anything canonically stated in the Numenera books), the inverted parallel between the Aeon Papacy and the Catholic Church is fairly evident, I think. (Although it can be taken too far. They’re not really a religion; they’re a sophisticated neo-cargo cult.)

But whereas the rest of the setting is Renaissance in character, I think when it comes to Aeon Papacy you’ll be more rewarded in looking for guidance to a different era of the church. Specifically, the church around the time of St. Peter, when the “church” was still heavily factionalized and trying to figure out exactly what its canon is going to be.

In other words, resist the impulse to make the Aeon Papacy this big, authoritative, well-organized force. (And note that the Aeon Priests predate the Papacy AND continue to exist independent of its reach!) So, yes, you can find Aeon Priests with a fair amount of regularity in the area of the Steadfast and the Beyond (although not so much as you get beyond their “heartland”). But the Aeon Priests should be possessed of just as much variance and weirdness as the numenera tht they study.

Brilliant article, I might have to steel your method thanks.

You comment on Simple Prep is precisely the reason I love running Numenera. I can do as much or as little prep as I feel is needed, I know from past experience its way too easy to turn GM prep into a chore. While on the subject of prep I can’t remember if you’ve reviewed it on the site but I find the Jade Colossus random ruin mapping generator helpful. You don’t need to follow it to the letter but it can remove some of the decision making that can bog down prep. Like so much of the core book it gives you enough ideas of something strange which you can turn into your own thing. For instance one of the rooms I created had a pool of liquid metal that was cold to the touch, it still leaves so much room for the GM to work out what’s it for, whys it here etc.

Also referencing you Creative Lubricant comment, I love how the game lets the GM just sit back and watch the players, take in what there thinking, what ideas and conclusion they have regarding the current situation. My players know this but sometimes I will make changes to the game based on their theories because they seem more fun then mine. Another factor I have found adds to the “Creative Lubricate” is the GM not rolling dice. I thought I’d miss rolling dice (Cypher system is the first time I’ve come across this design of the GM not rolling) but it seems to free up a level of mental energy that can be spent consternating on the players.

Putting past civilizations of the Ninth World in the context of Cthulhu Mythos is brilliant. Definitely resonates, will use it!. Perfect parallel.

One touch that I bring to the setting is to treat the DataSphere as a “divine” plane. Divine being unimaginably powerful AIs. Think Ummon from Hyperion. All kinds of powerful AI gods trapped there, split into factions, some trying to escape, some keeping them from escaping. Motives unknown.