Weird Discoveries is a collection of ten “Instant Adventures” for Numenera. The concept behind these instant adventures is basically what I talked about in Opening Your Gaming Table. I’ll let Monte Cook explain:

It’s Friday night. Your friends have gathered at your house. Someone asks, “What should we do tonight?” One person suggests watching a movie, but everyone else is in the mood for a game. You’ve got lots of board games, and that seems like the obvious solution, because they don’t take any more time to prepare than it takes to set up the board and the pieces.

Those of us who love roleplaying games have encountered this situation a thousand times. We’d love to suggest an RPG for the evening, but everyone knows you can’t just spontaneously play a roleplaying game, right? The game master has to prepare a scenario, the players need to create characters, and all this takes a lot of time and thought.

Cook’s solution to this problem is to create one-shot scenarios in a custom format that makes it possible for the GM to run a four hour session after quickly skimming 4-6 pages of information.

This basically boils down into three parts:

First, a two page description of the scenario’s background and initial hook.

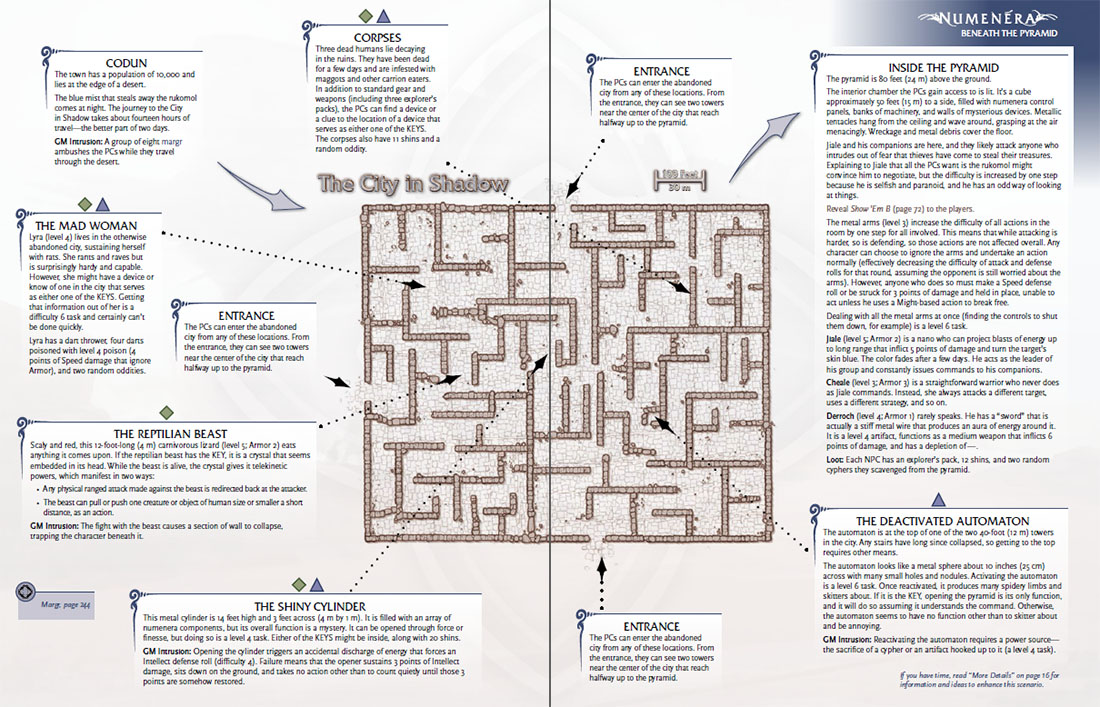

Second, a two page spread that generally looks something like this

and which contains the entire scenario. (This two page spread is the only thing you’ll need to look at while running the adventure.)

Third, two more pages of additional details that you can use to flesh out the scenario. (These pages are optional. If you don’t have time to read them, the evocative details they provide can easily be replaced by material improvised by the GM.)

The basic idea is that these scenarios give Numenera the same commitment profile as a board game: You pull out the rulebooks and dice. You quickly explain the rules. You hand out pregen characters to the players. And while they’re looking over their character sheets, you spend two or three minutes quickly reviewing a scenario.

Then you play for three or four hours and… that’s it. No prior prep commitment. No long-term commitment from the players. Just pick it up and play it.

WHERE THIS GOES A LITTLE WONKY

First, there’s the weird decision to kick off this book of stand-alone one-shots with two linked scenarios where one is clearly the sequel of the other. (The first scenario is “gaining access to the pyramid” and the second is “exploring the pyramid”.) This isn’t the end of the world and if those had been given at the end of the book as a sort of variant on the form, it probably would have been fine. But one of these scenarios is actually used as the free promo for the book, and I actually held off buying it for awhile because it appeared that the book wasn’t actually delivering on its promise.

Another bit of wonkiness comes from the way that Cook tries to streamline the presentation of the scenarios through the use of Keys. Each Key is some essential element of the scenario which could potentially be found in several different locations within the scenario. Each key is given a symbol, which is then used to indicate the locations where that key can be found.

For example, in a mystery scenario a Key might be:

Evidence that Supect A is innocent.

And that Key might be indicated by a little blue triangle. Then you look at the two page spread and you might see an NPC marked with a blue triangle, and their description will include:

If Bob is the KEY, then if the PCs really grill him, he’ll eventually admit that he saw Suspect A on the opposite side of town at the time of the murder.

In general, you’ll see two or three different places in the scenario where that little blue triangle shows up. That basically mirrors the redundancy suggested by the Three Clue Rule and it makes a lot of sense. And highlighting those essential bits with a visual cue in the form of the Key symbol also makes sense, because it flags the importance of including that bit for the GM.

A couple things mess this up, however: First, the table that tells you what each symbol means ISN’T located on the two page spread. So the simple elegance of the two-page spread is marred because you keep flipping back to that essential information.

Second, the “if” nature of the Keys tends to make it much more difficult to run the scenarios cleanly. The intention seems to be that the GM should control the pacing of when these keys are triggered, but in practice trying to keep track of the locations where a particular key is available (and whether or not this might be the last opportunity for it) requires a totality of understanding for the scenario which stands in sharp contrast with the goal of being able to run it off-the-cuff. (For off-the-cuff stuff, I generally want to be able to focus on the content directly in front of my nose without having to think about distant portions of the scenario.)

In general, you can probably just ignore the “if” portion of the text and run most of the scenarios with the Keys present in all of their potential locations. There are a handful of scenarios, however, where you can’t do this. (For example, a “missing piece” of a machine which can be in several different locations and actually be completely different things.)

In any case, these scenarios would be better if the keys were simply hardcoded. And I’d recommend altering them in whatever manner necessary to make that true before running them.

BAFFLING CARTOGRAPHY

The other thing that doesn’t quite work are, unfortunately, the two-page spreads themselves. These take two forms.

First, there are flowcharts which show how the PCs can move from one scene to another. (Go to the home of the murder suspect and find a clue that points to where the murder suspect is.) These mostly work fine, although there are a few scenarios with mysterious extra arrows that don’t actually represent any tangible information. (The intention with some of these seems to be “the PCs are done here and can now go follow a lead from another location”, but that’s ideographically confusing because the arrow implies that there is a lead here that should take you there.)

Second, and unfortunately more prevalent, are the spreads based around maps surrounded by blobs of text that have arrows pointing to various sections of the map.

The best of these are the dungeons, because they at least make sense. But they’re not very good dungeons. One keeps talking about how you can explore beyond the rooms shown on the map… except there are no exits from the rooms on the map. The other is composed of mostly empty rooms. And in both cases, most of the room descriptions don’t match the visual representation of the room that they’re pointing at.

This is because, as far as I can tell, the maps were drawn largely at random and then the various bits of content were “associated” with the maps by drawing arrows that just kind of point at whatever’s convenient. And this is even more apparent when you look at some of the other two-page spreads. For example, consider the spread we looked at before:

That’s supposed to be the map of a city. Except it obviously is not. And one of the content bubbles is “three dead bodies lie here”… except the associated arrow points into the middle of a wall. Another content bubble is “monster that’s explicitly moving around in the ruins”, but it has an arrow pointing to a very specific (and obviously completely meaningless) location

Another common technique here is “rough sketch of a wilderness area that’s radically out of scale with random arrows pointing at it”.

WHY IT DOESN’T MATTER

Because the scenarios are really good.

They cover a wide variety of nifty ideas backed up with fantastic art that’s designed to be shown to your players as evocative handouts (instead of featuring imaginary PCs doing things).

And despite my quibbles with some of the shortcomings of the presentation, the basic concept of the two-page spread fundamentally works: The maps and arrows don’t make any sense, but the essential content is nonetheless packaged in a format that makes it easy to simply pick up the adventure and run it with no prep time at all.

For my personal use, I’ll be basically ignoring all of the maps and using the content bubbles as either random encounters or logical progressions of an investigation (depending on the exigencies of the scenario). And I’ll take the time to lock down the Keys in a more concrete fashion, but I’m not anticipating that taking any more than 5-10 minutes per scenario, which is not an undue burden.

Ultimately, with ten full adventures, this book is incredibly valuable and I’m going to be getting dozens of hours of play out of it.

The final reason why the book’s shortcomings ultimately don’t matter, however, is because the roleplaying industry desperately needs more books like this: The board game renaissance is palpably demonstrating the power of memetically viral games that can be picked up and played as part of an evening’s entertainment. Games like Mice & Mystics and Mansions of Madness clearly demonstrate that the only reason traditional roleplaying games can’t hop on that bandwagon is because we’ve systematically ghettoized ourselves as an industry and as a hobby by embracing long-term, dedicated play as the only form of play.

With Numenera as its flagship, Monte Cook Games is fighting to change that. And I’m more than happy to help them out. (Particularly since their game is so much damn fun.)

Style: 4

Substance: 4

Author: Monte Cook

Publisher: Monte Cook Games

Print Cost: $24.99

PDF Cost: $9.99

Page Count: 96

ISBN: 978-1939979339

face: A strange, mask-like biotech growth which extrudes into a faceless visage.

face: A strange, mask-like biotech growth which extrudes into a faceless visage.