IN THE SHADOW OF THE SPIRE

IN THE SHADOW OF THE SPIRE

SESSION 29C: SKIRMISH IN THE CAULDRON

September 20th, 2008

The 16th Day of Kadal in the 790th Year of the Seyrunian Dynasty

The lamia ran down the staircase. Agnarr pursued it, finding himself back in the room with the iron cauldron. Agnarr managed to back it up against the cauldron. It howled again. The answering howl was closer.

While Agnarr kept the lamia pinned, the others descended the stairs, their shots ricocheting off the cauldron as the lamia desperately dodged back and forth. Then Tor used his lasso – catching the lamia by the legs and yanking them out from under her.

They moved in to finish her off, but at that very moment a second lamia – this one male – came racing into the room through the northern door. Seeing the female lamia injured and entangled he gave a howl of rage and bounded forward, throwing a healing potion to her as he came.

Tor moved to engage the second lamia while Agnarr stayed on the female. But as Agnarr closed in, her eyes locked onto his. Her pupils expanded until her eyes were a solid, tawny gold and Agnarr could feel them reaching out towards him. He could feel her mind reaching into his mind.

You should run away.

He couldn’t deny the command. Agnarr fled. The female lamia took advantage of the distraction to slink away around the cauldron, drinking the healing potion as she went.

Tee used her boots to levitate up to the ceiling. Pulling herself along she was able to emerge into the room out of the range of the lamia’s vicious claws, and from that elevated position she tried to get a clear shot.

But the male lamia wasn’t the last of the reinforcements. A large, muscular minotaur emerged from the northern passage “Verochin! What’s happening?”

“It’s Derimach!” the male lamia shouted back. “She’s hurt! There are at least six of them!”

“Friends of that meddlesome paladin!” The minotaur turned back towards the northern passage. “Stop hiding like cowards! Attack!”

The minotaur dashed forward, quaffing a potion that caused him to suddenly blur with speed. Bunching his powerful leg muscles he leapt up onto the thick rim of the immense iron cauldron.

“They’re drinking our wealth away!” Tee cried, firing at the minotaur.

Tor and Agnarr could do little about it because Verochin’s claws were keeping them thoroughly harried. Where the lamia’s blows landed, not only were huge gouges of flesh torn away, but a supernatural chill seemed to spread from the wounds – racing up into their minds and clouding their perception.

And now, scurrying down the hallway, came four vicious-looking goblins wielding serrated blades.

But then Ranthir dashed down the stairs, lowered his hands, and webbed the whole northern half of the room – trapping Verochin, the goblins, and the minotaur.

Tor seized the opportunity, turning and heading around the cauldron in pursuit of Derimach. As he came around the corner, however, the lamia’s eyes caught his and he could feel it trying to weave its way into his mind…

But he shook it off. With a bitter growl she threw herself at him.

Verochin, finding himself trapped in front of Agnarr, tried to wrench himself backwards out of Ranthir’s web. But he was too late. Agnarr took advantage of the moment and plunged his sword through the lamia’s back, ripping down through its front hips. In a gush of blood, Verochin fell.

The minotaur, meanwhile, was ripping his own way out of the webs. Moving along the rim of the cauldron he drew his massive greatsword. The blade – nearly as wide across as Agnarr’s thigh – flashed out and ripped open Tee. She fell from the sky, landing on her neck with a sickening snap.

Ranthir dashed to Tee’s side and raised his hands. A gout of fire rushed out of them, singeing the horns of the minotaur as he swung down into the cauldron for cover.

The minotaur levered himself back out of the cauldron and swung his sword low. Agnarr, who had been trying to move around to where Tor was engaging Derimach, only narrowly managed to dodge the blow. Fortunately, his help wasn’t needed: By the time he had gotten back to this feet, Tor had already killed the second lamia.

Ranthir recognized that the minotaur’s supernatural speed was ruinous. He quickly worked an enchantment that stripped the effects of the potion from the minotaur’s limbs.

The minotaur growled and then shouted back over his shoulder. “Verochin and Derimach are dead! I cannot escape! Flee! Get word to the others!”

“The others…?” Elestra, who was trying desperately to heal Tee’s grievous wounds, blanched.

Ranthir cast his own enchantment of speed, cracked a sunrod from one of his many pouches, and raced back up the stairs – hoping to circle around and catch the goblins before they could escape… although, truth be told, he wasn’t quite sure what he was going to do with them if he did catch them.

The minotaur lumbered down the length of the cauldron and then hurtled off the end. Flipping in mid-air his greatsword swept down along the floor, ripping open Agnarr’s back. Landing nimbly he spun to face Tor.

But Agnarr refused to fall. Stumbling forward his own greatsword ripped into the minotaur’s hide.

The minotaur’s counterstrike smashed Agnarr to the floor, but now he was bleeding profusely. He backed away from Tor and tried to cut his way out through the others… Tee, who had only just gotten back to her feet, was cut down again. (“I just healed her!” Elestra cried with dismay.)

But Tor’s furious flurry of blows would not be denied. The minotaur’s heavy blade couldn’t keep pace. He fell.

IN PURSUIT OF GOBLINS

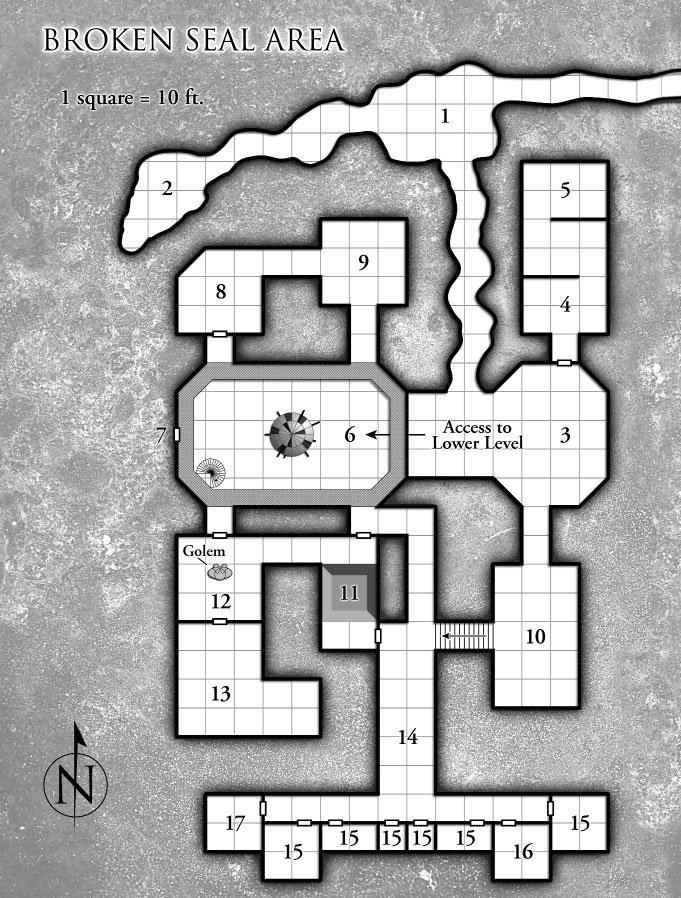

Ranthir, arriving back in the octagonal entrance chamber, found that most of the goblins were still stuck fast in his web. But one of them had ripped its way free and disappeared. Scarcely pausing for thought, he raced down the excavated tunnel – hoping to use his supernatural speed to catch it before it could reach the Nibeck Street mansion and disappear into the streets of Ptolus.

Tee, meanwhile, wasn’t far behind. As soon as her wounds had once again been healed by Dominic and Elestra, she had raced up the stairs and started circling around. Agnarr, meanwhile, began burning his way through the webs.

When Tee reached the entrance chamber, she drew the same conclusion Ranthir had. But without his enhanced speed, she didn’t think she would be able to catch up in time to make a difference. Instead she crossed over to the bewebbed goblins and started shooting them.

The last goblin, seeing his comrades picked off, suddenly found the desperate strength to rip his way free… but he had only stumbled a few steps when Tee placed a shot straight through his eye.

A few moments later, Agnarr finished burning his path through the webs… only to find Tee standing happily with her hands on her hips.

Tor, meanwhile, had hacked off the minotaur’s head – holding it up triumphantly by the horns.

But while the others celebrated, Ranthir was still working. He had raced several hundred feet down the length of the excavated tunnel and begun to think that the goblin had escaped after all. Just as he was about to give up hope, however, the sound of scampering feet came clearly to his ears. He redoubled his efforts.

As they drew near the side passage they had left unexplored, the goblin finally appeared in the light of his sunrod. Ranthir fired his crossbow, catching the goblin in the back.

With a screech of pained terror, the goblin veered off into the side passage.

Fearing an ambush, Ranthir cautiously cast his spells of clairvoyance and used them to peer down the passage from a safe vantage point. He watched as the goblin ran around a second corner and into a larger cave—

Which suddenly collapsed with a thunderous crash!

The goblin gave a final, squalling cry and then fell silent. A cloud of dust and debris billowed out of the catastrophe.

Unsure what to think – had the goblin triggered some sort of trap? or was it an elaborate ruse? – but confident now that the explored side passage represented a danger, Ranthir cast a different spell which would allow him to send a short message of exactly twenty-five words to his comrades:

I chased him to the cross corridor. He hit a trap. Come here now. I need help… Because I’m Ranthir. Hope they hurry, Erin.

DEJA SLIME

The others were stripping anything that looked valuable off the creatures they had slain. Tee shook her head sadly at the empty vials. Tor was disturbed to discover that Verochin, Derimach, and the minotaur had all worn bone-grafting rings like the one worn by the orcish woman in the Nibeck Street mansion. (These rings, however, could be removed. Possibly because it was post mortem.)

But when the wind whispered Ranthir’s message to them, they all ran up through the path that Agnarr had burned and down the excavated tunnel. When they had caught up to him, Ranthir quickly explained the situation.

Tee moved cautiously into the side passage. With Ranthir keeping an eye on her through his clairvoyance, she crept past a large boulder and up to the edge of the pit and looked down.

The goblin’s body was gone. But there were sharp stone spikes and she could see where it had landed. A trail of thick blood led towards a tunnel on the other side of the pit.

Everyone moved forward. Agnarr took the boots of levitation from Tee and used them to ferry the others across to the far side of the pit one at a time.

The tunnel on the far side of the pit ran up into a four-way intersection. Back to the south they could see where it curved back to dead-end in a boulder – the same boulder they had passed before in the original tunnel. Something had levered the boulder into position, concealing this passage in order to guide others into the collapsing pit trap.

They crossed the intersection into the far tunnel, which began to slope back down again. After thirty feet or so, this tunnel opened up into a larger cave with a slightly domed ceiling about ten feet high. Every surface in the cave was wet with the greasy-residue of mineral-choked water. Cracks in the walls revealed the moisture slowly seeping in and pooling, mostly along the north wall.

At the last possible moment, Tee – as she crossed the threshold of the room – was suddenly reminded of the caverns in which they had fought the olive slimes… and the tactics the slimes had employed. She dove forward and rolled onto her back—

Narrowly avoiding the gelatinous, iridescent, and (most importantly) motile blob of ogre-sized protoplasm that dropped from the ceiling! It wasn’t an olive slime, but it was just as disgusting.

Tee managed to squeeze off a shot, but then the creature sent out a thick pseudopod that caught her and began squeezing the breath from her body. The creature’s touch burned painfully and thick, acidic fumes tore at her throat.

Ranthir, recognizing the creature, shouted out a warning: “If you cut it, pierce it, or deliver an electric shock, it will split into multiple, smaller, and deadlier creatures!”

“You’re kidding!” Tor cried, pushing his half-drawn cutting, piercing, electrical sword back into its sheath.

Agnarr moved up and start beating on the creature with the flat of his blade, hoping that the bludgeoning and fire would force the creature to drop Tee… but it just kept tightening its grip.

Tor grabbed Tee’s dragon pistol from where it had fallen and began firing. Elestra drew her dragon rifle and did the same.

Tee’s vision was turning black by the time that Agnarr’s beating finally convinced the jelly to release her and attempt to grab him instead. The barbarian nimbly avoided the first pseudopod, but then the jelly lurched forward, slamming into Agnarr and smashing him into the wall.

As Tee climbed to her feet, Tor tossed the dragon pistol back to her and grabbed a club proffered by Dominic. He stepped up and swung away… the entire side of the jelly suddenly welled into a horrible, purple-black bruise that spread like dye through syrup.

CAVERNS OF CONFUSION

Ranthir gave a sudden cry. A large, insectile creature with a dull-golden carapace was lumbering down the hall towards him. Beady eyes stared out from a face dominated by half-domed membranes and curved, viciously-serrated mandibles. He recognized in it the tell-tale marks of a mage-warped creature… and the far more obvious signs of its danger.

Agnarr glanced at Tor. Tor waved for him to go. Agnarr ran back up the corridor towards where Ranthir was rapidly backpedaling.

Tee, meanwhile, took careful aim and shot the dragon pistol directly into the middle of the bruise Tor had raised. The blow punctured the thick, rind-like membrane of the jelly – viscous fluid seeped from its side.

The jelly twisted in place, turning its injured side away from them. But Tor swung again, raising a smaller bruise on its opposite side.

Ranthir was falling back towards the rest of the group. Agnarr reached the intersection where he’d been standing, but as he rounded the corner the umber-colored hulk was already there – its claws whipped out and ripped at his skin, and then, as Agnarr was spun about by the force of the blow, the creature’s long, vicious mandibles closed about Agnarr’s neck. The only thing that saved Agnarr’s life was the heavy iron collar that he wore.

Back by the jelly, Tee fired again. And again her shot struck the middle of the bruise that Tor had raised. This proved too much for it. With a horrific shudder, the creature’s insides burst through the twin holes, leaving nothing behind but a spreading pool of thick slime. Its gelatinous skin lay like a disgusting, discarded garment.

Trapped between the mandibles of the umber hulk, Agnarr’s torso was ripped again and again by the creature’s claws. And then, whipping its head about, it threw him against the wall. Agnarr’s head struck hard and he slipped into unconsciousness.

The creature took a menacing step towards Ranthir. But then Tor was there, racing up the passage and drawing his sword.

But as the rest of the group rallied toward it, the bulging membranes on the creature’s face began to vibrate. The sound seemed to reach into their minds and scramble their thoughts. Some of them turned on their comrades. Others began to babble incoherently (although it was hard to tell the difference with Agnarr).

Complete confusion reigned. Erin screamed in Ranthir’s mind: “I don’t like the buzzing!” But the hulk did it again and again and again, even as its claws were battering away at Tor.

Elestra, resisting the mental barrage, slid in next to Agnarr and healed his wounds. But as Agnarr tried to struggle back to his feet, the creature slammed one of its massive claws into his back. Agnarr, nearly slain by the blow, feigned his own death… allowing the creature to turn its full attention back to Tor.

Tor’s blows, meanwhile, were proving ineffective. Besieged both mentally and physically, he was barely able to catch his balance under the frenzied battering he was receiving from the creature’s claws.

But he was keeping the creature engaged. And while he did, Tee was blasting away with her dragon pistol. Each shot was blowing away large chunks of the creature’s carapace.

And then Agnarr, choosing his moment carefully, rolled to his knees almost directly beneath the creature and thrust up through its lower thorax.

This horrific distraction allowed Tor a moment to catch his footing. He took advantage of the moment and brought his blade down heavily onto the creature’s head. From the point of impact, a horrendous pattern of cracks spread down its face.

It stumbled back and Tee, taking careful aim, placed a shot precisely where Tor had struck it. The entire top of the creature’s head was blasted away, revealing a pulsing, purplish-green brain.

The creature roared three times, its membranes vibrating their staccato patterns of psychic turmoil. Tor and Agnarr were driven to senseless babbling. Dominic fled in terror down the hall. Seeaeti, driven mad by the noise, leapt at his own master’s throat – his vicious attack sending the badly-wounded Agnarr back into unconscious oblivion.

But the creature, perhaps mortally wounded, suddenly lurched to one side. The vibrating of its membranes stopped and its claws began vibrating instead – vibrating faster than their mortal eyes could see. It pulverized the stone of the tunnel wall and passed from sight. Heavy stone fell into its wake, preventing any thought of pursuit as the befuddled troupe gathered its wits.

Running the Campaign: Looting Consumables – Campaign Journal: Session 30A

In the Shadow of the Spire: Index