The hexcrawl is a game structure for running wilderness exploration scenarios. Although it was initially a core component of the D&D experience, the hexcrawl slowly faded away. By 1989 there were only a few vestigial hex maps cropping up in products and none of them were actually designed for hexcrawl play. That’s when the 2nd Edition of Advanced Dungeons & Dragons removed hexcrawling procedures from the rulebooks entirely.

It wasn’t until Necromancer Games brought the Wilderlands back into print and Ben Robbins’ West Marches campaign went viral that people started to rediscover the lost art of the hexcrawl. The format has returned to prominence in recent years through releases like the Kingmaker campaign for Pathfinder and Tomb of Annihilation for D&D 5th Edition.

BASIC HEXCRAWL STRUCTURE

Hexcrawls are only one way of running wilderness travel (see Thinking About Wilderness Travel for some other options) and there are actually many different varieties of hexcrawls and schools of thought on how they should be designed or run. “True” hexcrawls, however, share four common features.

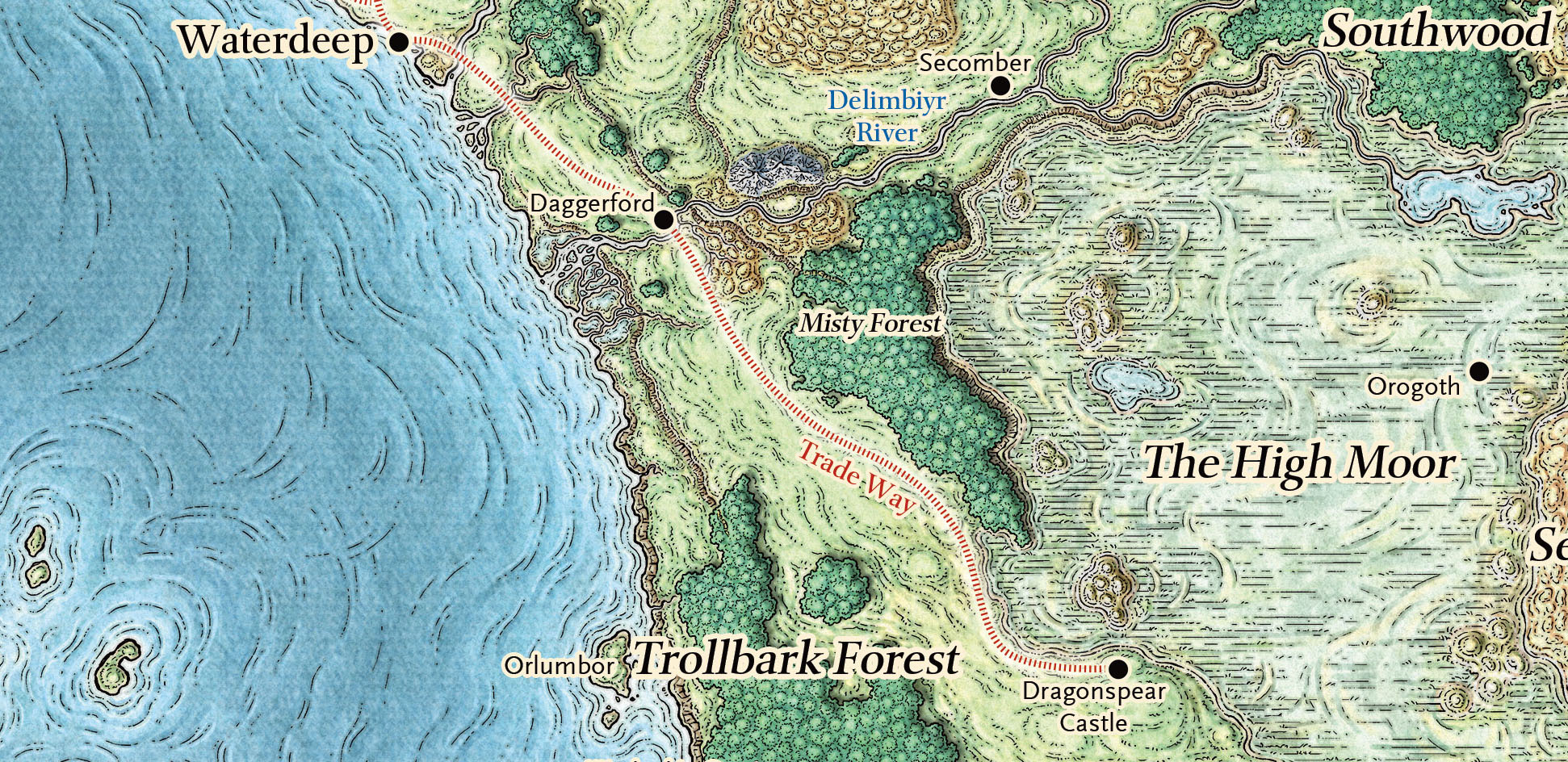

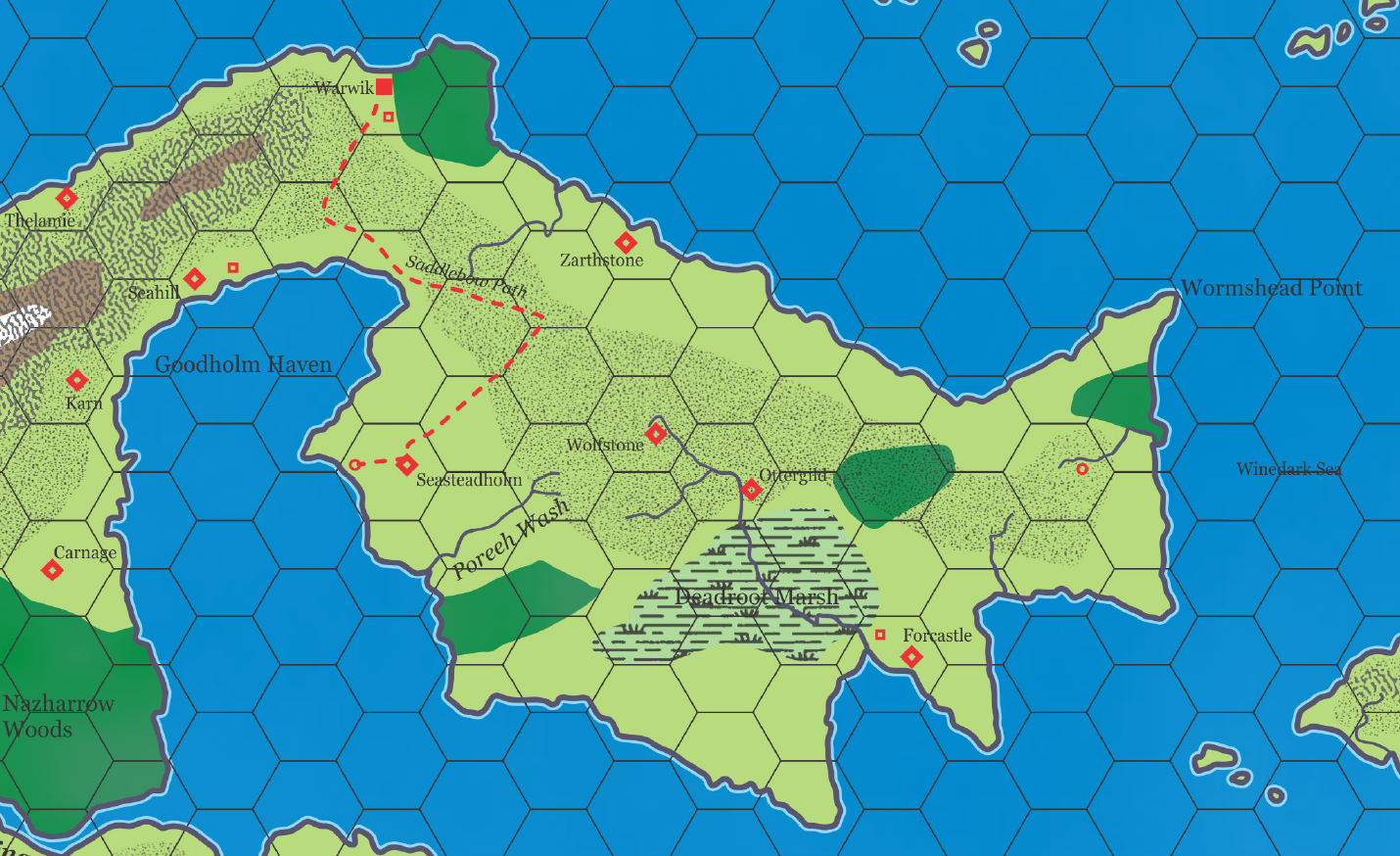

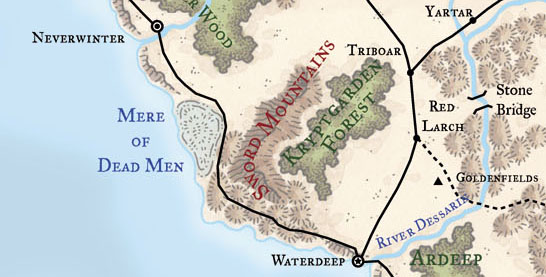

- They use a hexmap. In general, the terrain of the hex is given as a visual reference and the hex is numbered (either directly or by a gridded cross-reference). Additional features like settlements, dungeons, rivers, roads, and polities are also often shown on the map.

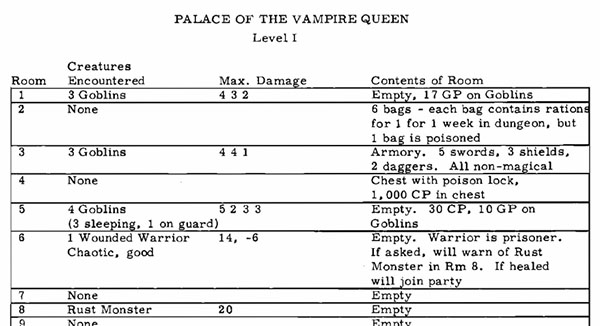

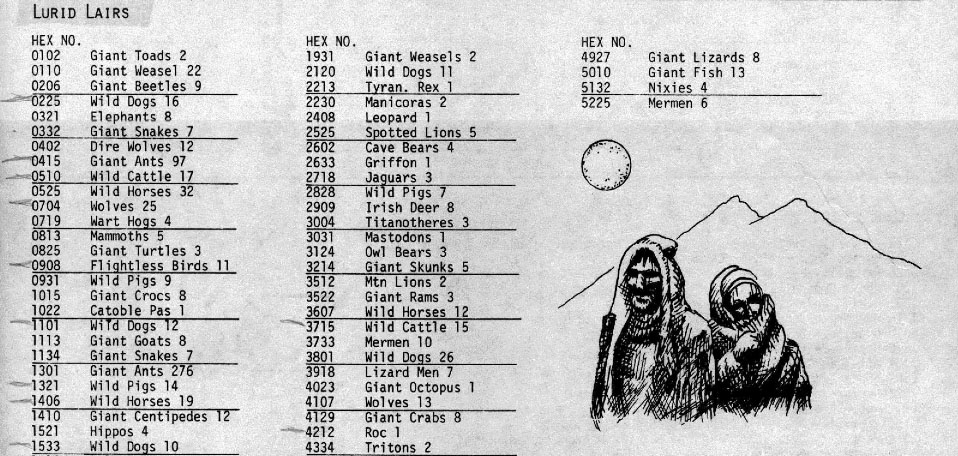

- Content is keyed to the hexmap. Using the numbered references, some or all of the hexes are keyed with locations and/or encounters.

- Travel mechanics determine how far the PCs can move and where they move while traveling overland. After determining which hex the PCs are starting in, the GM will use these mechanics (and the decisions the players make) to track their movement.

- When the PCs enter a hex, the GM will tell them the terrain type and determine whether or not the keyed content of the hexmap is triggered: If so, the PCs experience the event, encounter the monsters, or see the location. (There is often a 100% chance that the keyed content will be triggered.)

Around this basic structure you can build up a lot of additional features and alternative gameplay. For example, mechanics for random encounters and navigating (or, more importantly, getting lost in) trackless wastes are quite common. Hex-clearing procedures were once quite common, too, as an antecedent for stronghold-based play.

THE ALEXANDRIAN HEXCRAWL

In 2012, before 5th Edition was released, I wrote Hexcrawls: This series discussed hexcrawl procedures and laid out a robust structure for prepping and running hexcrawls in both 3rd Edition and the original 1974 edition of the game.

The Alexandrian Hexcrawl had several key design goals.

First, I wanted a structure that would hide the hexes from the players. In my personal playtesting, I found that the abstraction of the hex was extremely convenient on the GM’s side of the screen (for tracking navigation, keying encounters, and so forth), but had a negative impact on the other side of the screen: I wanted the players interacting with the game world, not with the abstraction. Therefore, the hexes in the Alexandrian Hexcrawl were a player-unknown structure.

Second, the structure was explicitly built for exploration. The structure, therefore, included a lot of rules for navigation, getting lost, and finding your way again. It was built around having the players constantly making new discoveries (even in places they’d been to before).

Third, the hex key features locations, not encounters. It’s not unusual to see hexcrawls in which encounters are keyed to a hex, like this one from the Wilderlands of the Magic Realm:

A charismatic musician sits on a rock entertaining a group of Halfling children. He sings songs of high adventure and fighting Orcs.

While the Alexandrian Hexcrawl system could be used with such keys, my intention was to focus the key on content that could be used more than once as PCs visit and re-visit the same areas. (This is particularly useful if you’re running an open game table.) In other words, the key is geography, not ephemera, with encounters being handled separately from the key.

Fourth, the system is built around the assumption that every hex is keyed. There may be rare exceptions — the occasional “empty” hex, for example — but if this is happening a lot it’s generally an indication that your hexcrawl is at the wrong scale. This tends to create two problems in actual play: First, it results in very poor pacing (with long spans of time in which navigational decisions are not resulting in interesting feedback in the form of content). Second, the lack of content equates to a lack of structure. One obvious example of this is that hexcrawls with vast spans of empty space lack sufficient landmarks in order to guide navigation.

(You run into similar problems if you have lots of densely packed hexes featuring multiple locations keyed to each hex: The abstraction of the hex stops working and your hexcrawl procedures collapse as the PCs engage in lots of sub-hex navigation.)

THE (MANY) RULES OF 5th EDITION WILDERNESS TRAVEL

Since the release of 5th Edition, I have been frequently asked to update the Alexandrian Hexcrawl to the new system. Unfortunately, there have been a couple impediments making this more difficult than it might first appear.

First, 5th Edition is not designed for hexcrawls. 3rd Edition didn’t feature hexcrawl play, either, but its rules were fundamentally grounded in a mechanical tradition that had originally been designed to support hexcrawl play, and it was therefore fairly straightforward to graft those procedures back onto those mechanics.

5th Edition, ironically, reintroduced hex-mapping to the core rulebooks, but mechanically trivializes or strips out essential mechanical elements that make hexcrawls (or, more generally, the challenges of wilderness exploration) work in actual play.

Second, the rules for overland travel and wilderness exploration in 5th Edition are a little… fraught.

- The rules are scattered haphazardly throughout the rulebooks and difficult to pull together into any sort of cohesive procedure.

- The rules actually change from one book to the next: The exploration procedures and travel distances in Tomb of Annihilation, for example, are just slightly different from those in the core rulebooks for no apparent reason. And the ones in the Wilderness Kit are different once again.

- The rules are vague in bafflingly inconsistent ways. For example, there is a specific rule about how many pounds of food you need each day. And there’s a specific rule about how many pounds of food you get while doing the Forage activity while traveling. It seems like those would link up, but the rule for how often you make a Forage check is “when [the DM] decides it’s appropriate.” Which could be every hour, every day, every week, or literally anything else.

- Most of the wilderness rules are not actually found in the SRD, making them inaccessible for projects outside of the Dungeon Master’s Guild.

Although these factors have largely stymied my efforts in the past, I’ve decided to more or less embrace the vague chaos of it all: If there is no coherent set of rules in the first place, then no one will probably care if I change them.

So my final design goal is to maintain the large, macro structures of 5th Edition wilderness travel that tie into other elements of the game – like how various classes modify your travel pace, for example – but otherwise tweak and change whatever needs to be altered to make things work.

Go to Part 2: Wilderness Travel

5E HEXCRAWLS

Part 2: Wilderness Travel

Part 3: Watch Actions

Part 4: Navigation

Part 5: Encounters

Part 6: Watch Checklists

Part 7: Hex Exploration

Part 8: Cheat Sheet

Hexcrawl Tool: Rumor Tables

Hexcrawl Tool: Spot Distances

Hexcrawl Tool: Tracks

HEXCRAWL ADDENDUMS

Sketchy Hexcrawls

Designing the Hexcrawl

Running the Hexcrawl

Connecting Your Hexes

Special Encounter Tables

Describing Travel

The Layered Hexcrawl