This article originally appeared in the March 2001 issue of Games Unplugged.

That’s New Style: showing that the existing way is not the only way; there are different ways of playing and designing these games. Violence does that too.

James Wallis, Hogshead Publishing

BARON MUNCHAUSEN

Prior to 1998 Hoghsead Publishing was a small English company known only for their licensed production of Warhammer Fantasy Roleplaying. Then, in 1998, they released a small 24 page pamphlet entitled The Extraordinary Adventures of Baron Munchausen, A Superlative Role-Playing Game in a New Style, Devised & Written By Baron Munchausen.

Munchausen was a clever little game, written by James Wallis under a simple affectation: The game was not designed by Wallis, but by the famous Baron Munchausen himself in the year 1798 while staying with a friend of his, the publisher John Wallis, in London. Wallis, however, realized that the manuscript was simply unacceptable for it time period. Instead he sealed the manuscript, which was later discovered by his descendant – James – who decided the time has come to show this marvelous creation to the public at large.

Munchausen was a clever little game, written by James Wallis under a simple affectation: The game was not designed by Wallis, but by the famous Baron Munchausen himself in the year 1798 while staying with a friend of his, the publisher John Wallis, in London. Wallis, however, realized that the manuscript was simply unacceptable for it time period. Instead he sealed the manuscript, which was later discovered by his descendant – James – who decided the time has come to show this marvelous creation to the public at large.

It became the surprise hit of the convention, and changed the direction of Hogshead Publishing forever.

What truly made the game click for everyone who laid eyes upon it was the simple fact that, at least in one way, the title was no joke: It truly was a “role-playing game in a New Style”.

It works like this: You get together with a bunch of your friends over some drinks and roleplay a group of eighteenth century noblemen telling stories of their fantastic adventures to one another (just as the Baron himself might). A very specific set of mechanics, involving challenges and duels which structure the stories as they are being told, guide the play of the game. There are winners and losers.

It was a roleplaying game completely out of the norm which D&D established and every game since has followed, yet it was a game which featured roleplaying. Many games claim to be something you’ve never seen before – but Baron Munchausen actually was.

Since its release, the game has gone on to become the most successful RPG under twenty-five pages – earning its way to an Origins nomination, foreign language editions, and general critical acclaim. The game was so successful, in fact, that James Wallis, who is also Hogshead’s founder an director, decided it was time to launch a whole new line of games: New Style.

VIOLENCE

Next up on the figurative chopping block was Violence: The Roleplaying Game of Egregious and Repulsive Bloodshed – a game so bloody, brutal, dark, and evil that its designer’s true name has to be concealed under the pseudonym of “Designer X”.

Well, okay. Not really. Greg Costikyan’s name is clearly visible underneath the Designer X “label” on the game’s front cover. The game is bloody, brutal, dark and evil (with players taking on the roles of contemporary criminals who go around killing people) – but it’s also a satire. It is self-confessedly designed to nauseate you and digust you. To get you “down in the muck and wallow with the pigs”. To make you sit back and openly wonder about why a large portion of the gaming population consists of people who are no more than “perverted little Attilas” desiring nothing more than “violence of the most degraded kind; suppurating wounds, whimpering innocents pleading vainly for mercy, torture and rapine and cannabilism”.

Well, okay. Not really. Greg Costikyan’s name is clearly visible underneath the Designer X “label” on the game’s front cover. The game is bloody, brutal, dark and evil (with players taking on the roles of contemporary criminals who go around killing people) – but it’s also a satire. It is self-confessedly designed to nauseate you and digust you. To get you “down in the muck and wallow with the pigs”. To make you sit back and openly wonder about why a large portion of the gaming population consists of people who are no more than “perverted little Attilas” desiring nothing more than “violence of the most degraded kind; suppurating wounds, whimpering innocents pleading vainly for mercy, torture and rapine and cannabilism”.

Suffice it to say that this was not what anyone expected out of a sequel to Baron Munchausen. But then there was Puppetland…

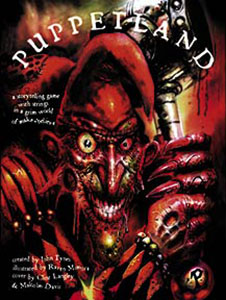

PUPPETLAND / POWER KILL

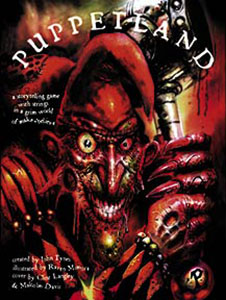

“The skies are dim always since the Maker died.

The lights of Puppettown are the brightest beacon in all of Puppetland, and they shine all the time. Once the sun and the moon moved their normal courses through the heavens, but no more. The rise of Punch the Maker-Killer has brought all of nature to a stop, leaving it perpetually winter, perpetually night. Puppets all across Puppetland mourn the loss of the Maker, and curse the name of Punch – but not too loudly, lest the nutcrackers hear and come to call with a sharp rap-rap-rapping at the door.”

So we are introduced to Puppetland, designed and written by John Tynes.

The world of Puppetland is the nightmare of a child, rendered through the lives of puppets who are more than puppets. It is a startlingly powerful vision, rendered in an intense barrage of prose,  which instantly captures your heart’s imagination. It is a surgical blade slicing through the detritus of maturity and laying open the veins of your inner child.

which instantly captures your heart’s imagination. It is a surgical blade slicing through the detritus of maturity and laying open the veins of your inner child.

The game is based around three simple rules (“An hour is golden, but it is not an hour”; “What you say is what you say”; and “The tale grows in the telling, and is being told to someone not present”), and what impresses me most about it is the way in which Tynes effortlessly blends storytelling with gaming. Often when you hear the phrase “storytelling game” what it really means is that the game has been reduced to a set of muddy mechanics that serve “storytelling” by being easily fudged out of existence.

Not so with Puppetland. Here the game creates the story; and the story creates the game. In other words, the mechanics of gameplay are instrumental in the creation of a Puppetland story On the flip side of the coin, the nature of a Puppetland story (heavily influenced by the storytelling mechanics of puppet shows) are the foundation of the game’s mechanics. The symmetry reinforces itself, creating one of the most brilliant game designs of recent memory.

If that was all that this marvelous little New Style pamphlet had to offer, it would be more than worth the price: But Tynes wasn’t content with merely one game, he had to include two. And so, when you flip Puppetland over, you will find Power Kill – a second complete RPG within 24 pages.

If that was all that this marvelous little New Style pamphlet had to offer, it would be more than worth the price: But Tynes wasn’t content with merely one game, he had to include two. And so, when you flip Puppetland over, you will find Power Kill – a second complete RPG within 24 pages.

Power Kill, like Violence, is a satirical commentary on the violent mores of a gaming session, with the conceit that the characters the players play are inmates in an asylum. But there is an interesting mechanic at the heart of Power Kill: What John Tynes calls a “roleplaying metagame”. As he says, Power Kill “is not a game unto itself – it is instead a layer of ‘game’ that you add to whatever” RPG you are already playing. So, for example, you might take a session of D&D and then add Power Kill onto it (so that the players are playing inmates whose violent fantasies take the form of D&D adventures).

Although used for satire in Power Kill, this concept of a “roleplaying metagame” has within it a nascent potential which we should expect to see impacting many game designs in the years to come.

PANTHEON

Robin D. Laws saw that John Tynes had placed two games within one cover. And, lo, Laws was angry with Tynes, and he smote the ground, and declared unto the Heavens: “I shall design five games and place them within over. I shall describe them in 24 pages. And I shall have true fame throughout the ages.” And as he said, so it came to pass.

You don’t believe that happened? Well, perhaps not. But the next New Style book was, indeed, Robin D. Laws’ Pantheon and Other Roleplaying Games – topping John Tynes’ accomplishment by including five complete RPGs.

The game in question are the titular Pantheon itself, as well as Grave and Watery, Boardroom Blitz, The Big Hole, and Destroy All Buildings – covering the gamut from godhood to B-rate horror to Japanese monster movies. Each of these games use the Narrative Cage Match system, relying on a simple storytelling/roleplaying mechanic with the quirk that there is no GM: Play proceeds from one player to the next, with each contributing a new sentence to the story. This basic mechanic is then fleshed out with a challenge system, specific guidelines, and a scoring system.

The game in question are the titular Pantheon itself, as well as Grave and Watery, Boardroom Blitz, The Big Hole, and Destroy All Buildings – covering the gamut from godhood to B-rate horror to Japanese monster movies. Each of these games use the Narrative Cage Match system, relying on a simple storytelling/roleplaying mechanic with the quirk that there is no GM: Play proceeds from one player to the next, with each contributing a new sentence to the story. This basic mechanic is then fleshed out with a challenge system, specific guidelines, and a scoring system.

Yes, you heard me right: A scoring system. These are games you play to win. There are no sacred cows in the house of New Style.

In any case, Hogshead had struck gold again: Laws had created a set of games which were not only a solid kick in the pants of the traditional RPG form, but also pure fun through and through. So what do they have up their sleeve next? So far nobody will say. But that only means that it’s going to be big!

NEW STYLE

At the end of the day, what do we see in the New Style line? Three trends, all valuable:

First, there are the games which serve as a commentary on the status quo of the RPG industry. We all have unspoken assumptions. Unquestioned premises. Unexamined beliefs. There are things we hold to be such basic truths that we never stop to ask ourselves why we believe them. These things shut down our creative horizons, and close our minds to a limitless array of possibilities.

Violence and Power Kill tear into these without even pausing to look back. Read Violence, James Wallis says, “and you’ll never be able to look at a dungeon-bash the same way again”. And that’s the point: Through satire and bluntness these New Style games tear apart the assumptions we hold. They encourage you to open your mind and look at all the little voids you’ve left unexplored because what you’ve always known to be true was keeping you from looking for the stuff that didn’t fit within your preconceptions.

And that’s when the other half of the New Style line comes rushing in to fill up all those voids which have been torn open. Baron Munchausen, Puppetland, and Pantheon

Last, but not least, the New Style line is about accessibility. They are complete games in a small package, priced at only $5.95 – a price which lends itself to impulse buys in a way that most RPGs can only dream of enviously. Plus, the games which aren’t deliberate commentaries directed at existing roleplayers go to the other extreme – as John Tynes says: “I think you could hand a New Style game to someone with no roleplaying experience and have a real shot at them making it work, certainly a better shot than if you handed them a typical RPG rulebook.”

The New Style games have a strong possibility of being a cornerstone in the future of roleplaying. And if they are, we’ll all be better off for it.

Next: An Interview with James Wallis

Tweet. Soon I was getting offers of work, or seeing stuff I made up for Jonathan become part of his Over the Edge game, and not long after that I was doing this game design thing full-time.

Tweet. Soon I was getting offers of work, or seeing stuff I made up for Jonathan become part of his Over the Edge game, and not long after that I was doing this game design thing full-time. If Greg Stafford, Sandy Petersen and the rest of the Chaosium team had managed to fit Runequest, Call of Cthulhu, Ringworld, Stormbringer, and Superworld into 24 pages, would it be one game or five?

If Greg Stafford, Sandy Petersen and the rest of the Chaosium team had managed to fit Runequest, Call of Cthulhu, Ringworld, Stormbringer, and Superworld into 24 pages, would it be one game or five?

Violence isn’t a great leap forward in game design, but… well… the best analogy I can think of is

Violence isn’t a great leap forward in game design, but… well… the best analogy I can think of is