I had someone drop me an e-mail requesting a quick overview of the various editions of D&D. In the context of the Reactions to OD&D essays, I thought it might be a useful reference for people who are a little less familiar with the history of the game.

If you want more details on the history of D&D, the “Editions of Dungeons & Dragons” article at Wikipedia is a pretty solid resource. If you want an exhaustive detailing of every single change made between each printing of the early rulebooks, then the Acaeum is an excellent resource.

The only important thing you need to remember here is that D&D split into two separate games in 1977: Advanced Dungeons & Dragons and Dungeons & Dragons (with the latter often being referred to as Basic D&D or BD&D).

The terms used below are not official, but they are the most commonly used nomenclature in the fan community.

DUNGEONS & DRAGONS

With the exception of the Rules Cyclopedia, all of these games were sold as boxed sets.

OD&D (Original Dungeons & Dragons, White Box): The original edition of the game designed by Dave Arneson and Gary Gygax, first published in 1974 as a boxed set comprising three volumes — Men & Magic, Monsters & Treasure, and Underworld & Wilderness Adventures. These books would receive various errata in subsequent printings (with the most notable change being the purging of references to Tolkien’s works following a lawsuit from the Tolkien Estate), but remained substantially unaltered.

Holmes Edition (1977): Published as the Basic Set in 1977. Eric Holmes is credited as having “edited” the book, but it’s actually a complete re-design and re-edit of the original game.

Moldvay Edition (1981): A completely revised Basic Rulebook and a brand new Expert Rulebook published in 1981. Tom Moldvay is credited for “editing” the Basic Set. David Cook and Steven Marsh are credited for “editing” the Expert Set. (I’m not clear on why Tom Moldvay is usually the only guy who gets credit for this version of the game. But he is.)

BECMI (1983 – 1985): Comprising the Basic Rules, Expert Rules Companion Rules, Master Rules, and Immortal Rules. (With the exception of the Expert Rules, these boxed sets each contained two volumes — one for players and one for the DM. The first two sets are, once again, completely revised.) These sets are variously credited as being “edited”, “compiled”, or simply “by” Frank Mentzer.

Rules Cyclopedia (1991): A single-volume hardback which collected the BECMI rules with minimal alteration (basically just applying errata). However, the Rules Cyclopedia lacked the rules for Immortals (which were published separately as the Wrath of the Immortals ruleset).

In addition to these rules, a total of five different Basic Sets were produced between 1991 and 1999 under the names The Dungeons & Dragons Game or The Classic Dungeons & Dragons Game. These all differed from each other in various ways, but all of them were designed to serve as “teasers” or “primers” for the Rules Cyclopedia edition of the game. So if you’re considering distinct iterations of the rules, they can be ignored.

ADVANCED DUNGEONS & DRAGONS

All of these editions were published as three separate core rulebooks: A Player’s Handbook, a Dungeon Master’s Guide, and a Monster Manual (the last of these under various titles, as described below).

AD&D 1st Edition (1977 – 1979): Designed by Gary Gygax. The original Monster Manual was published in 1977, followed by the Player’s Handbook in 1978 and the Dungeon Master’s Guide in 1979. These books were re-issued with new covers in 1983 (which are easily recognizable due to their orange spines), but were not revised. Also referred to as AD&D1.

Unearthed Arcana (1985): TSR officially identified Unearthed Arcana as a core rulebook. Since it included not only expansions but also alterations in the game, it is sometimes referred to as the Edition 1.5.

AD&D 2nd Edition (1989): The 2nd Edition was published in 1989 as the Player’s Handbook, Dungeon Master’s Guide, and Monstrous Compendium. The re-design is primarily credited to David “Zeb” Cook. In 1993 the Monstrous Compendium was replaced with the Monstrous Manual. In 1995, these books were re-issued with new covers and a new layout (but no meaningful change to the rules). Also referred to as AD&D2.

Player’s Options (1995): Also referred to as Edition 2.5. Three optional core rulebooks known as the Player’s Options released in 1995: Combat & Tactics, Skills & Powers, and Spells & Magic. There was also the DM’s Option: High Level Campaigns.

D&D 3rd Edition (2000): Released as the Player’s Handbook, Dungeon Master’s Guide, and Monster Manual. This edition was designed by Monte Cook, Jonathan Tweet, and Skip Williams. Also referred to as D&D3 or 3rd Edition.

D&D 3.5 (2003): Revised versions of the 3rd Edition core rulebooks. The revision team was Rich Baker, Andy Collins, David Noonan, Rich Redman, and Skip Williams.

SUMMARY

So, if you count the Unearthed Arcana and Player’s Options as distinct edition, then there have been 10 editions of D&D:

OD&D (1974)

Holmes D&D (1977)

Moldvay D&D (1981)

BECMI / Rules Cyclopedia (1983)

AD&D 1st Edition (1977)

AD&D 1st Edition + Unearthed Arcana (1985)

AD&D 2nd Edition (1989)

AD&D 2nd Edition + Player’s Options (1995)

D&D 3rd Edition (2000)

D&D 3.5 (2003)

And then, of course, 4th Edition in 2008.

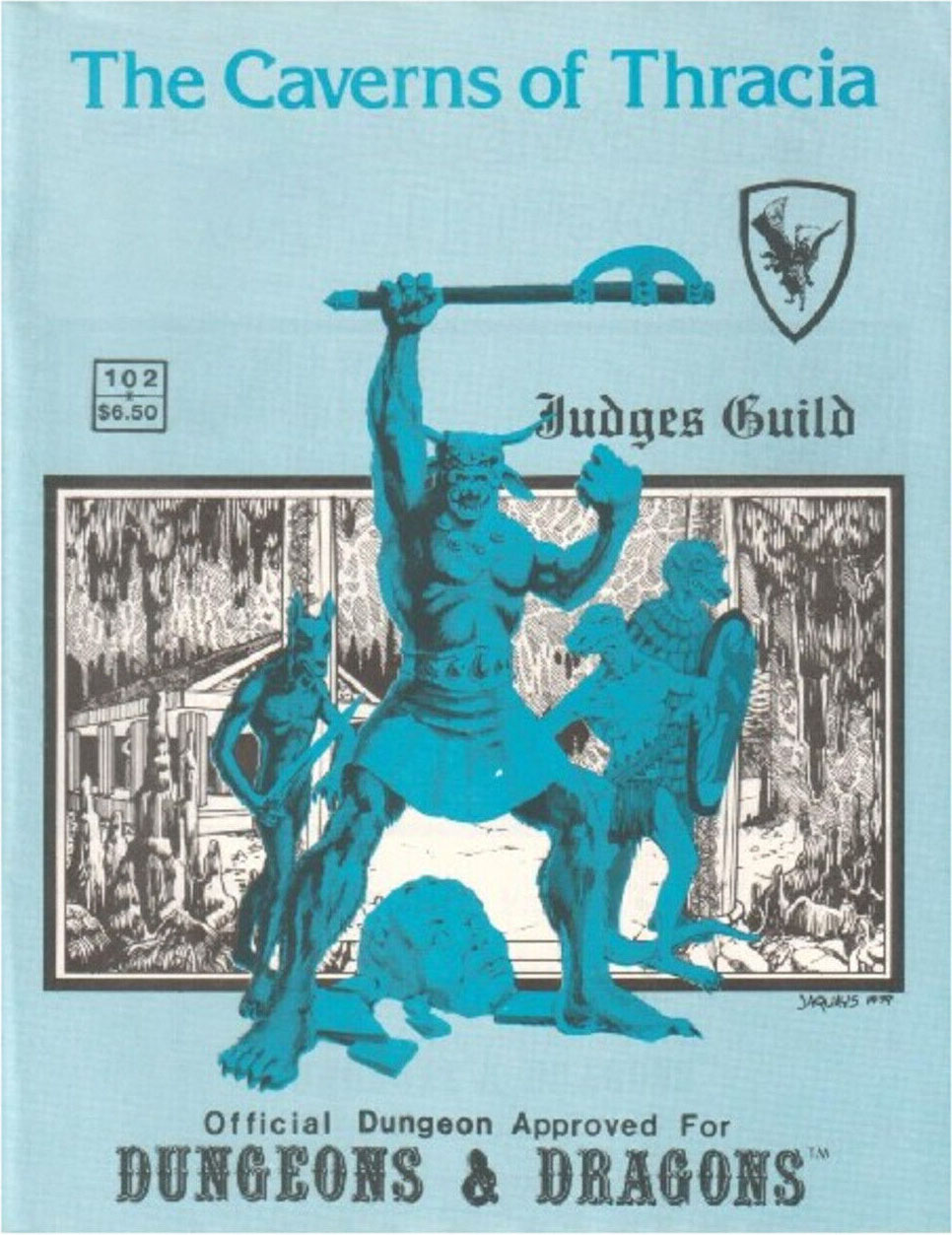

This time the random 1d8 roll determined that they would be approaching the ruins from the southwest. As a result, they ended up practically stumbling over a short, squat building of gray-black stone that was hidden within a small copse of trees. A rusty gate on one side of the building led to a narrow flight of stairs that plunged down into darkness.

This time the random 1d8 roll determined that they would be approaching the ruins from the southwest. As a result, they ended up practically stumbling over a short, squat building of gray-black stone that was hidden within a small copse of trees. A rusty gate on one side of the building led to a narrow flight of stairs that plunged down into darkness.