Yesterday I rolled out some experimental rules for revising hydras and creating new hydroid creatures. Today we’re going to put them into practice with a few sample creatures.

Bear in mind that this is still an installment of an Untested column: The general rules for hydroids haven’t been tested and these specific monsters even less so. If you do find occasion to use them in your own games, please circle back and let us know how it went!

HYDRALING

Baby hydras — also known as hydralings – are two-headed serpents, only developing the legs of an adult hydra during adolescence. The mothers of hydralings have been seen to deliberately bite off one of the heads from their offspring, prompting the growth of an additional head. Some have hypothesized that this is because hydralings never truly sleep (since one of their heads is always awake), but it’s more likely an instinctual action which prompts (or is prompted by) the hydraling’s development.

HYDRALING

Medium monstrosity, unaligned

Armor Class 13 (Natural Armor)

Hit Points Special

Speed 40 ft., swim 20 ft.

STR 12 (+1)

DEX 15 (+2)

CON 12 (+1)

INT 2 (-4)

WIS 10 (+0)

CHA 6 (-2)

Skills Perception +3, Stealth +4

Senses passive Perception 13

Challenge 1/2 (100 XP)

Amphibious. A hydraling can breathe air and water.

Hydroid. The hydraling has two heads. For every 10 points of damage the hydra suffers, one of its heads dies. If all of its heads die, the hydraling dies.

At the end of its turn, the hydraling grows two heads for each of its severed heads, unless it has taken fire damage since the head was severed. A hydraling can have a maximum of five heads.

Multiple Heads. While the hydraling has more than one head, it has advantage on saving throws against being blinded, charmed, deafened, frightened, stunned, and knocked unconscious.

For each additional head beyond one, it gets an extra reaction that can be used only for opportunity attacks.

While the hydraling sleeps, at least one of its heads is awake.

ACTIONS

Multiattack. The hydraling makes as many bite attacks as it has heads.

Bite. Melee Weapon Attack: +4 to hit, reach 5 ft., one target. Hit: (1d4 +2) piercing damage.

TENTACULAR ABOMINATION

A dog-size creature with eel-like skin. It has no head, but its back is a writhing mass of tentacles.

TENTACULAR ABOMINATION

Medium monstrosity, unaligned

Armor Class 15 (Natural Armor)

Hit Points: Special

Speed 30 ft.

STR 17 (+3)

DEX 12 (+1)

CON 14 (+2)

INT 6 (-2)

WIS 13 (+1)

CHA 6 (-2)

Skills Perception +5

Senses Blindsight 60 ft., passive Perception 15

Challenge 3 (700 XP)

Pack Tactics. The tentacular abomination has advantage on an attack roll against a creature if at least one of the tentacular abomination’s allies is within 5 ft. of the creature and the ally isn’t incapacitated.

Hydroid. The tentacular abomination has five tentacles. For every 10 points of damage the abomination suffers, one of its tentacles dies. If all of its tentacles die, the abomination dies.

At the end of its turn, the abomination grows two tentacles for each of its severed tentacles, unless it has taken acid damage since the head was severed.

Multiple Heads. While the tentacular abomination has more than one head, it has advantage on saving throws against being blinded, charmed, deafened, frightened, stunned, and knocked unconscious.

For each additional head beyond one, it gets an extra reaction that can be used only for opportunity attacks.

While the abomination sleeps, at least one of its heads is awake.

ACTIONS

Multiattack. The abomination makes as many tentacle attacks as it has tentacles.

Tentacle. Melee Weapon Attack: +5 to hit, reach 10 ft., one target. Hit: (1d6+3) bludgeoning damage. The target is grappled (escape DC 13) by one of the abomination’s tentacles. Until this grapple ends, the tentacular horror can’t use that tentacle on another target.

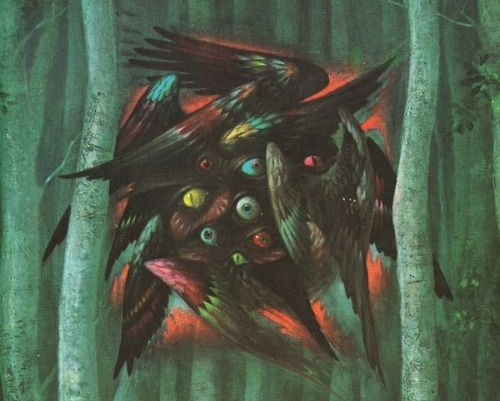

LENGLIAN SERAPHIM

Wings. Dozens of wings clustered together as if shielding a central mass (although no such mass exists within the impossible dimensional toroid of the Lenglian seraph), with eyes opening and shutting between the wings. Some Lenglian seraphs are also known to emit smoke or aurora-like, multi-colored halos as their wings continue to fold and unfold, stretching, reaching, searching, beating the air around them.

(It is also not unusual for Lenglian seraphs to be confused for a swarm of winged creatures, particularly from a distance.)

LENGLIAN SERAPHIM

Large celestial, lawful good

Armor Class 17 (Natural Armor)

Hit Points Special

Speed fly 80 ft.

STR 22 (+6)

DEX 21 (+5)

CON 14 (+2)

INT 21 (+5)

WIS 16 (+3)

CHA 19 (+4)

Saving Throws Wis +7

Skills Perception +7

Damage Resistance Radiant; Bludgeoning, Piercing, and Slashing from Nonmagical Attacks

Condition Immunities Charmed, Exhaustion, Frightened

Senses Truesight 120 ft., passive Perception 17

Languages All, Telepathy 120 ft.

Challenge 12 (8,400 XP)

Innate Spellcasting. The seraph’s spellcasting ability is Charsima (spell save DC 17). The seraph can innately cast the following spells, requiring only verbal components:

- At will: bless, detect evil and good

- 1/day each: augury, commune

Hydroid. A Lengling seraph has thirty-five wings. For every 5 points of damage the seraph suffers, one of its wings is severed. If all of its wings are severed, the seraph dies.

At the end of its turn, the seraph grows two wings for each of its severed wings, unless it has been splashed with unholy water since the wing was severed or is under the effects of a bane spell.

Many Eyed. A seraph has eyes proportionate to its wings. While the seraph has more than one wing, it has advantage on saving throws against being blinded, charmed, deafened, frightened, stunned, and knocked unconscious.

For every five wings the seraph has, it gets an extra reaction that can only be used for opportunity attacks.

ACTIONS

Multiattack. The seraphim can make one wing attack for every five wings it has.

Wing. Melee Weapon Attack: +8 to hit, reach 5 ft., one target. Hit: (1d8+6) bludgeoning damage.

Radiant Gaze (Recharge 5-6). One creature that the seraph can see within 60 feet of it must make a DC 17 Constitution saving throw, taking 70 (20d6) radiant damage on a failed save, or half as much damage on a successful one.

LEGENDARY ACTION

Can take one legendary action. Only one legendary action can be used at a time, and only at the end of another creature’s turn. Spent legendary actions are regained at the start of each turn.

Buffeting Wings. The seraph beats its wings. Each creature within 10 ft. of the seraph must succeed on a DC 17 Dexterity saving throw or take 1d6+6 bludgeoning damage and be knocked prone. The seraph can then fly up to half its flying speed.