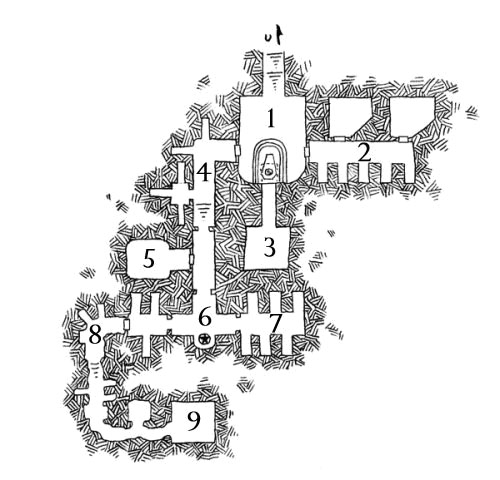

On that note, let’s take a closer look at the practical techniques I use when stocking my hexes.

#0. HAVE A MAP

Our primary focus here is stocking hexes. But before you can do that, you need the map you’ll be keying.

First, figure out how big you want your map to be. For the reasons we discussed above, I recommend a 10 x 10 or 12 x 12 map. 100 or 144 hexes should be more than enough to get started.

Second, place the home base for the PCs in the center of this map. (This way, as noted, they can go in any direction without immediately riding off the edge of your prep.) The home base might be:

- A small town or city

- An expedition’s base camp

- A keep

- An outpost

- A dimensional portal

- A crashed spaceship

There’s no limit here except your imagination. The key thing is that the PCs need to have a reason to keep coming back to this location. (This usually means some form of resupplying between one expedition and the next.)

Third, grab some hexmapping software. Current options include:

You can also use other world-mappers and then just drop a hex grid on top of your map, but I recommend creating a true hex map with one clearly defined terrain type per hex. (It will make travel modifiers a lot clearer.)

I also suggest large blocks of similar terrain, which can then immediately double as your regions. (Remember that any individual hex is huge. Just because you threw down “forest” as the predominant terrain type, it doesn’t mean there isn’t a lot of local variation within it.)

Finally, I recommend having two or three different types of terrain immediately adjacent to the home base: If the PCs go north, they enter the mountains. If they go west, they enter the forest. If they head south or east they’re crossing the plains. This gives a clear and immediate distinction which provides a bare minimum criteria that the PCs can use to “pick a direction and go.”

Fourth, throw down some roads and rivers.

You’re done.

#1. BE CREATIVE, BE AWESOME, BE SINCERE

Before we get into any tips, tricks, shortcuts, or cheats, first things first: Do some honest brainstorming and pour some raw creativity onto the page.

The neat ideas you’ve been tossing around inside your head for the past few days? Everything your players think would be cool? Everything you think would be cool? Everything you wish the last GM you played with had included in the game?

Put ‘em in hexes.

Then think about the setting logically: What needs to be there in order for the setting to work? For the stuff you’ve already keyed to work?

Get ‘em in hexes.

Bring your creativity to the table. And make sure everything you include is awesome, because life is too short to waste time on the mediocre or the “good enough” or the “I guess I need to do that.” If there’s something that feels mundane or generic, give it a twist or add something extra. (The Goblin Ampersand can be a good technique here.)

Finally, throughout this entire process, be sincere. I think it’s really important to stay true to yourself when you’re doing design work: You have a unique point of view and a unique aesthetic. Even when you’re bringing in material or inspiration from other sources, apply it through your own perspective and values.

#2. JUMP AROUND

It can be useful to start at Hex A1, go to Hex A2, and then systematically proceed on through the A’s before starting the B’s.

But if you’re working on A3 and you get a cool idea that belongs on the other side of the map, don’t hesitate: Jump over there and key up Hex F7.

That is not only useful from a practical standpoint: It also feels great when you get to column F and discover three-quarters of the hexes have already been filled.

#3. STEAL

Okay, you’ve filled a couple dozen hexes, but now you’re starting to run out of ideas. What next?

Steal.

If you’re reading this blog, I’m guessing you’ve got a stack of adventures that you’ve collected over the years. Go pull your favorite location-based adventures off the shelf and start plopping them down into your hexes.

For example, consider the 5E adventure anthologies. Tales From the Yawning Portal has:

The Sunless Citadel

The Sunless Citadel- The Forge of Fury

- The Hidden Shrine of Tamoachan

- White Plume Mountain

- Dead in Thay (The Doomvault)

- Against the Giants (Hill Giant Stronghold)

- Tomb of Horrors

All of these locations could be dropped directly into your hexcrawl, although you might want to push the last three into hexes beyond your initial map as long-term goals for the PCs to work towards.

Next, flip open your copy of Candlekeep Mysteries:

- Book of Ravens (Chalet Brantifax)

- A Deep and Creeping Darkness (Vermeillon)

- Price of Beauty (Temple of the Restful Lily)

- Zikran’s Zephyrean Tome (Zikran’s Laboratory)

- Zikran’s Zephyrean Tome (Haunted Cloud Giant Keep)

And just like that, we’ve keyed twelve more hexes.

Old school editions featured a lot of these “here’s a cool location” adventures, so if you’re willing to adapt material you can unlock 50 years worth of cool options. In my Thracian Hexcrawl, for example, I used:

- Caverns of Thracia

- S3 Expedition to the Barrier Peaks

- B3 Palace of the Silver Princess

- Temple of Elemental Evil

- L3 Deep Dwarven Delve

- Return to White Plume Mountain

- Touched by the Gods

And more.

Having 30+ years of collecting to fall back on is nice, of course. But even if you don’t have that kind of gaming library, you can find a ton of great stuff online for free. For example, the One Page Dungeon Contest is basically an all-you-can-eat smorgasboard for this sort of thing; I’ve already mentioned Dyson Logos’ maps (only one of many free map resources); and so forth.

#4. STEAL MORE

No. Seriously. Go steal stuff. Pillage and loot with wild abandon.

Not every adventure can be dropped straight into a hex, but even adventures that aren’t explicitly location-based will often feature cool locations that you can ripped out and easily adapted.

And the more you’re willing to adapt, the more you’ll be able to use. For example, “The Joy of Extradimensional Spaces” in Candlekeep Mysteries features Fistandia’s Mansion, an extradimensional sanctum accessible from a magical book in Candlekeep.

- Drop the extradimensional component and you can drop the whole building into a hex.

- Change the extradimensional access point to a statue or shrine or giant magic rune carved into the wall of a box canyon and you can drop that into a hex.

- Give the mansion multiple magical access points and you can drop them into multiple (And you might as well toss the original magic book into a dungeon’s treasure horde somewhere, too.)

Grab any non-urban 5E campaign book you’re not interested in running and you’ll be able to continue harvesting. From Hoard of the Dragon Queen, for example, you could grab:

The village of Greenest as the campaign’s home base

The village of Greenest as the campaign’s home base- Raider Camp (p. 16)

- Dragon Hatchery (p. 23)

- Carnath Roadhouse (p. 41)

- Castle Naerytar (p. 43)

- Hunting Lodge (p. 62)

- Skyreach Castle (p. 76)

As you’re harvesting material like this, you may start to notice patterns. For example, we’ve got a bunch of giant-related content now:

- Hill Giant Stronghold (from Tales of the Yawning Portal)

- Haunted Cloud Giant Keep (from Candlekeep Mysteries)

- Skyreach Castle (cloud giants from Hoard of the Dragon Queen)

How could we hook the lore of these locations together?

Also, when you’re harvesting material from a campaign book, you’re jettisoning the original connective material between the locations (which was probably some sort of linear plot), but the lore connections are still there. You can go one step further and strip those out, too. (Usually by adapting or genericizing them into something else.) But you usually don’t have to: By plopping them into a hexcrawl, you’ve effectively remixed the original adventure. In fact, you can use node-based scenario design to diversify these connections. Check out How to Remix an Adventure to trivially add even more depth to your hexcrawl. (You can, of course, use these same techniques to link up other hex keys, too.)

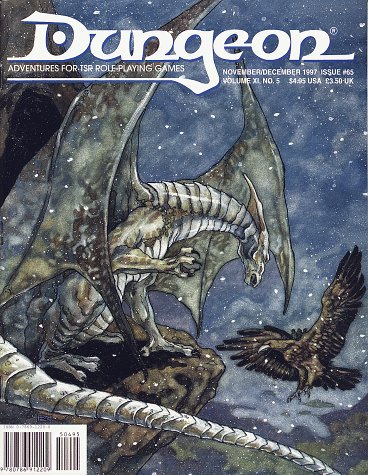

Another resource I love for this are back issues of Dungeon magazine. Sadly these are harder to come by these days, but each issue usually had a half dozen different adventures. Some could be dropped directly into hexes; others could be easily harvested for locations.

For example, let’s flip open Dungeon #65:

- “Knight of the Scarlet Sword.” This adventure details the Village of Bechlaughter and the magical silver dome in the center of the village which serves as home to a lich. Use the whole village or just use the dome.

- “Knight of the Scarlet Sword” also contains the Caves of Cuwain — the tomb of a banshee. Another location that can be used as a key entry.

“Flotsam” is a side trek featuring a couple of pirates who pretend to be legitimate merchants; they lure people onto their ship by offering legitimate passage and then rob them on the high seas. It doesn’t seem immediately appropriate for a forest hex key, but what if the PCs found this ship — and its weird, seemingly crazy crew — just sitting in the middle of the forest? Maybe it’s a witch’s curse or a strange haunting. Or just crazy people.

“Flotsam” is a side trek featuring a couple of pirates who pretend to be legitimate merchants; they lure people onto their ship by offering legitimate passage and then rob them on the high seas. It doesn’t seem immediately appropriate for a forest hex key, but what if the PCs found this ship — and its weird, seemingly crazy crew — just sitting in the middle of the forest? Maybe it’s a witch’s curse or a strange haunting. Or just crazy people.- “The Ice Tyrant” is a heavily plotted adventure, but we could start by ripping out the fully-mapped Lodge and placing it along any convenient road that needs an inn.

- “The Ice Tyrant” also contains a map for a Sentinel Tower occupied by evil dwarves. This can also be dropped straight into a hex. (Could it be connected with the dark dwarves from “The Forge of Fury” that we used earlier?)

- “The Ice Tyrant” finally features the Keep of Anghanor — guarded by a white dragon and containing a bunch of bad guys. (Could this dragon be related to the dragon cults from the Hoard of the Dragon Queen locations?)

- “Reflections” is another side trek, this one involving a cavern where a will o’ wisp has imprisoned a gibbering mouther. That’s another hex done!

- “Unkindness of Raven” is a location-based adventure triggered by stumbling across Crawford Manor while wandering through the wilderness. This is easy!

- “The Beast Within” is a location-based adventure triggered by stumbling across a werewolf’s cottage in the wilderness. Plop it in!

And there you go. One random issue of Dungeon and you’ve got another nine hexes keyed. Pick up a dozen issues and you could probably key a full 10 x 10 hex map entirely from the magazine.