A fellow by the name of John Warburton was once a huge fan of Elizabethan theater. He spent a great deal of time collecting original manuscripts of Elizabethan and Jacobean plays. By the time he was done, he had most likely accumulated the largest and most impressive such collection in the known world.

One day, John Warburton sat down to enjoy a nice pie that his cook had prepared for him. Stuck to the bottom of it he found a piece of paper with Elizabethan handwriting on it.

His cook had been tearing pages off the scripts and used them to cook pies on. And she’d been doing it for years. According to Warburton, dozens of scripts had been destroyed by his illiterate cook.

It’s a tale so horrifying that it could very easily be true.

Some, perhaps shying away from the idea of a cultural conflagration infinitely more pathetic than the Library of Alexandria, suggest that Warburton may have simply invented the story in order to claim greater treasures than he had ever truly possessed. But whatever the case may be, very few Elizabethan or Jacobean play scripts have survived to the modern day. The vast majority of the plays which have survived (including all of those commonly ascribed to Shakespeare) have done so in editions published during the 16th and 17th centuries shortly after they were originally performed. (The academic slogan of “publish or perish” has never rung quite so true.)

It should perhaps be noted at this juncture that the search for original Elizabethan play manuscripts is not merely an endeavor to fill reliquaries with interesting bits of historical trivia: Finding an author’s original manuscript would obviously and immediately resolve dozens or even hundreds of textual problems introduced by the text’s imperfect transmission through scribes and printers. (In cases where a text’s lineage can be tracked, it’s possible to trace the slow accumulation of its errors, like a game of Telephone played in slow motion across decades of history).

But of perhaps equal importance is the fact that in an era before ubiquitous printing and copying, plays were produced from handwritten scripts: Scribes would prepare a fair copy of the author’s foul papers. And then additional scribing would prepare handwritten sides for each actor (listing their cues and their lines).

These handwritten documents were the heart of Elizabethan theater. And the few of them that survive provide an invaluable and unique insight into how that theater operated.

The play most often referred to as The Second Maiden’s Tragedy survived to the 20th century only as a handwritten document. It was among those texts which survived Warburton’s cook, apparently being professionally bound by Warburton along with several other scripts into a volume which is now referred to as Lansdowne 807 in the collection of the British Museum.

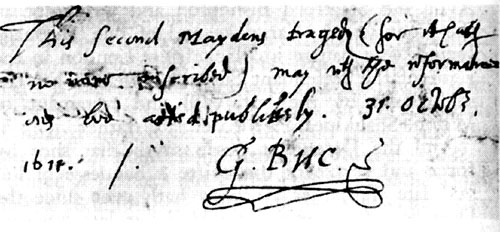

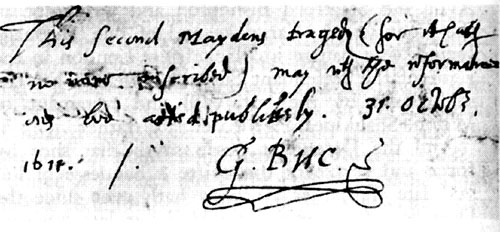

And this script does, in fact, provide invaluable insight. For example, the reason the play is referred to as The Second Maiden’s Tragedy is because King James’ censor, George Buc, wrote on its back page:

This second Maydens tragedy (for it hath no name inscribed) may wth the reformations be acted publikely. 31 Octobr.

1611. /. G. Buc.

And throughout the script we can see the “reformations” (i.e. censorship) of Buc, and the exact ways in which he modified the play both in terms of form and content.

The script also served as the promptbook for the King’s Men. This tells us a lot about how much recorded detail the Jacobean theater felt was necessary for staging and re-staging a play, but it also tells us about how prompters wrote their cues and the physical format of the script (which can, in turn, tell us something about what Jacobean printers were looking at as they set the type for a playscript and, by extension, what information can be gleaned from the printed copies of those plays). For example, we can identify the play as having belonged to the King’s Men because the names of several actors have been written into the script’s cues by the prompter. This might seem like a small thing, but beyond its immediate import in terms of identifying the place of The Second Maiden’s Tragedy in history, it can inform in a broader sense.

In Romeo & Juliet, for example, there is a stage direction in the earliest printed versions of the play which reads “Enter Will Kemp”. Will Kemp was the name of the clown who worked for the Lord Chamberlain’s Men and for many years it was not uncommon to see commentators on the play conclude that Shakespeare wrote his characters with specific actors in mind (since he had referred to the character by the name of actor he intended to play him). It is certainly possible (and even likely) that Shakespeare did so. But as we can see from The Second Maiden’s Tragedy, it’s just as possible (and even likely) that Kemp’s name was added to the script by the prompter.

Another interesting feature of the Second Maiden’s Tragedy manuscript is the method of deletion: Although often individual words and lines will be struck out (in a familiar manner), longer passages (and some shorter ones) are frequently marked for deletion (by both the censor, the prompter, and the scribe) by simply placing a large X in the margin next to the offending text.

Turning to Romeo & Juliet again, we can find in the original printed versions of the text numerous passages which contain strange repetitions. For example, in Act IV, Scene 1, Friar Lawrence tells Juliet:

Then as the manner of our country is,

In thy best robes uncover’d on the bier

Be borne to burial in thy kindreds’ grave:

Thou shall be borne to that same ancient vault

Where all the kindred of the Capulets lie.

But with The Second Maiden’s Tragedy as our guide, we can hypothesize what happened. One of these lines was marked for deletion, but the mark for deletion was ignored (or misunderstood) by the compositor responsible for typesetting the play. The passage should be properly read as:

Then as the manner of our country is,

In thy best robes uncover’d on the bier

Be borne to burial in thy kindreds’ grave:

Thou shall be borne to that same ancient vault

Where all the kindred of the Capulets lie.

(This is a smaller example. Other examples in Romeo & Juliet can run to half a dozen verse lines or more before restarting.)

In short, The Second Maiden’s Tragedy is a fascinating document. It’s one which has been periodically picked up, examined, and re-examined countless times over the centuries since it was first written. But in the 1990’s, interest in The Second Maiden’s Tragedy suddenly spiked to a fever pitch.

And it was all because of a man named Charles Hamilton.

Go to Part 2

Originally posted August 2010.

DH Boggs at Hidden in Shadows has put together an absolutely fascinating bibliographic analysis of the earliest versions of the turn undead ability in D&D.

DH Boggs at Hidden in Shadows has put together an absolutely fascinating bibliographic analysis of the earliest versions of the turn undead ability in D&D.