Tagline: Another excellent, if not so cheap, Cheapass Game.

Cheapass Games has created quite a reputation for itself. Producing games from the cheapest materials possible, they create highly affordable games with highly original premises. Almost all of their games have catchy titles and/or taglines, and their concepts are usually intriguing and amusing enough in their own right so that, even if the gameplay doesn’t catch your fancy, the product is still well worth the cost of entry.

Cheapass Games has created quite a reputation for itself. Producing games from the cheapest materials possible, they create highly affordable games with highly original premises. Almost all of their games have catchy titles and/or taglines, and their concepts are usually intriguing and amusing enough in their own right so that, even if the gameplay doesn’t catch your fancy, the product is still well worth the cost of entry.

And I say that as if their gameplay is usually poor. Quite the opposite is true – Cheapass Games doesn’t just have a reputation for their cheapness, they have a reputation for the high quality and playability of their game concepts. In short, Cheapass has ushered in a breath of fresh air to game design. Because they can produce games with such a low overhead they can experiment in many different directions very quickly, and with comparatively low risk. As a result you can see Cheapass play with and discard innovative game mechanics that other companies would be forced to milk for years, if they ever tried them in the first place.

Which brings us to Falling, an innovative and relatively unique card game. As with all of Cheapass Games’ products the first thing I heard about it was the tagline: “Everyone is falling, and the object is to hit the ground first. It’s not much of a goal, but it’s all you could think of on the way down.”

Instantly intrigued I surfed over to the Cheapass Games website and went digging around for more information. I came across an article written by James Ernest, the game’s designer and the driving force behind Cheapass Games, discussing some advanced tactics he had recently discovered… long after releasing the game.

I knew right then and there that I had to possess a copy of Falling. Most games, you understand, are like Sorry or Candyland — what little strategy and tactics there are in such games was known by the designers before the first playtest. It is the games which take on a life of their own, which have hidden complexities and dynamic interactions between their components which result in strategies and tactics which the designer never dreamed of, which are the very best games. Games like Chess and Diplomacy. If Falling was truly that type of game, and it contained the same type of powerful innovation found in other Cheapass Games, it was definitely packed with potential.

Unfortunately I couldn’t find Falling anywhere. I scanned the Cheapass racks (with their distinctive white envelopes) in, literally, half a dozen stores without any luck.

Why not? Because Falling is sold as a card pack, in one of those little cardboard boxes, on playing-card stock, for a price of $9.95. From Cheapass Games? What the heck?

Well, after playing the game it has become quickly apparent why this is the case. The cards simply have to be of a higher stock than your typical Cheapass game because, as the box says, Falling is a “frenetic” card game. Without the durability of an actual playing card, anyone owning Falling would quickly find themselves in need of a new deck.

So is this Cheapass Game worth a not-so-cheap price tag?

Hell, yeah.

THE RULES

Falling reminds me of another favorite game of mine, Twitch (from Wizards of the Coast and reviewed elsewhere on RPGNet). They’re both copyrighted for 1998 and therefore I won’t engage in pointless speculation as to which came first – it is far more likely a case of simultaneous inspiration (or drawing from some primal source with which I am wholly not familiar).

I say they remind me of each other, because both of them are “turn-less cardgames” – instead of following a set play order, like your typical card game, both Twitch and Falling feature simultaneous play by all the players at the table. No lazy downtime from these games (I actually managed to work up a hefty sweat while dealing for Falling).

In Twitch, simultaneity is accomplished because the basic mechanic of the game is determining the play order – the card one person plays determines who goes next, and if anyone else can play before that person can, then that person has to pick up the discard stack.

Falling, on the other hand, does it in a completely different fashion. One player is the dealer. Throughout the game all that the dealer does is deal cards, he doesn’t play at all. In fact, the dealer is dealing cards continuously throughout the game, proceeding sequentially from one player to the next. While the dealer deals, the players are all playing cards on themselves and against each other all at the same time.

Cool, huh?

In an unmodified situation (such as the very beginning of the game), each player starts with a single “stack” of cards. The dealer will deal one card to each player’s stack, and then move onto the next player (remember, once he starts dealing, he deals continuously). As the players receive cards, they can pick up one card at a time (and only the card on the top of a stack), which they can play on themselves or on another player.

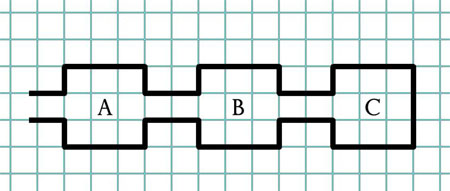

As cards are played, however, things will change very quickly. The main mechanic in Falling are cards known as “riders”. Essentially, a rider informs the dealer how to deal to a player. There are three types of riders:

Split. A split card tells the dealer to start a new stack for the player (so he would deal one card to the existing stack, and then deal a second card to start a second stack). On subsequent turns, the dealer will deal one card to each stack (however, a player can get rid of a stack if he can play through all the cards in that stack before the dealer returns to him – a dealer only has to deal to stacks he can “see”, unless there are no stacks present in which case he automatically creates one).

Hit. A hit card tells the dealer to deal an additional card to each of the player’s stacks.

Skip. A skip card tells the dealer not to deal to that player this time around.

A player can only have one rider on them at a time. The dealer picks up the rider when he finishes its instruction (so a rider is only in effect for one turn).

In addition to the riders there are also “action” cards, which can be used to manipulate the riders in various ways:

Stop. A stop card destroys the rider. Put the rider in the discard pile, along with the stop pile.

Push. A push card takes a rider which has been played on you, and “pushes” it onto another player.

Grab. A grab card takes a rider which has been played on someone else, and “grabs” it – applying the rider to yourself.

Finally there are the Ground cards, which are placed at the bottom of the deck before the deal begins. If you are dealt a ground card you have hit the ground and are out of the game. The only way to avoid this is to “Stop” the ground card as soon as it is played (in which case it is placed back in the deck by the dealer). Because the ground cards are all grouped together once they start coming out it is generally useful to “Skip” your turn and to “Hit” other people (since having them dealt more cards makes it less likely that they can avoid the ground cards or stop them effectively).

There are a couple of extras (including, ironically, the “Extra” cards) – but that’s the core of the game.

DOES IT WORK?

Yes. Absolutely, positively. We had a rough start-up, since we had several neophytes who couldn’t quite get their heads around the “simultaneous play” portions of the game, but after a few trial runs (during which the dealer dealt very slowly and stopped often so that people could ponder how the game worked) we were able to quickly vamp things up to speed.

And at that point the game rocked. Just like Twitch people became speed demons around that table.

One thing we found of particular interest, though, was the differences in gameplay based on the speed of the dealer. We had a couple of very methodical dealers, who would deal at a steady, even pace. This allowed a bit more of personal reserve and tactical consideration. On the other hand, the speed demon dealers – who would race around the table as quickly as possible – inspired a rapid-response style of play in which you did your best to disadvantage the other players while keeping your disadvantage as limited as possible.

IS IT FUN?

You’re kidding, right?

You’re kidding, right?

I have a very large shelf of games (which, coincidentally, is coming to be dominated more and more by Cheapass Games). However, there is a small, select handful which get played time and time again. After one short evening of play, Falling has joined that select list. It is fun, it is engaging, and it is captivating. We were playing at a sizeable family gathering, and our initially small group had soon maxed out my deck many times over. Falling was drawing people to it from across the room.

So get out there. Scour your store for it (it may very well be in the last place you look, as it was for me). Buy it. You won’t regret it.

Style: 5

Substance: 5

Author: James Ernest

Company/Publisher: Cheapass Games

Cost: $9.95

Page Count: n/a

ISBN: n/a

Originally Posted: 1999/08/16

I absolutely adore real-time card games. They are so much fun! Unfortunately, most of the people in my immediate circle of gamers are completely disinterested and I almost never get to play them any more. They also seem to have fallen out of fashion. It makes me all frowny-faced.

It should be noted that Paizo reissued this game. I don’t own the new version, but my understanding is that the rules have not been changed and the only difference is that the game has been re-themed to feature Paizo’s crazy goblins.

For an explanation of where these reviews came from and why you can no longer find them at RPGNet, click here.