Tagline: A masterpiece. ‘Nuff said.

First, let us look at the design philosophy of the Heavy Gear line of products. Like any other roleplaying game on the market the first product you are expected to buy is the rulebook. Currently in its second edition as I write this, the rulebook contains a regrettably brief coverage of the world of Terra Nova, the setting of the game. ‘Regrettably’, I say, because the very best thing about the game (despite the fact that the Silhouette engine on which it is based is one of the best on the market today) is the rich and inspiring world in which it is set. This isn’t much of a shortcoming, however, because the main rulebook contains not only a complete roleplaying game but a complete tactical game as well (which is beautifully based on the same basic system and principles). The rulebook is a masterpiece of system design in its own right.

After purchasing the rulebook your next step should be to pick up Life on Terra Nova (also in its second edition as I write this). Life on Terra Nova is the key to a magnificent, layered, believable, living world. It is without equal in terms of its originality, depth, and potential. Don’t be fooled into thinking that because the game is called Heavy Gear that the primary focus of the game is necessarily on the gears – the primary focus is on the characters and the world. The gears (as DP9 likes to point out) are merely the coolest selling point available. Like the rulebook, Life on Terra Nova is a masterpiece.

Once you own these two books you have the core of the Heavy Gear product line in your possession. At this point (as a roleplayer) you can go in several directions: You could purchase the host of technical supplements for the game (primarily for Tac use, but also useful for roleplaying campaigns with a technical or gear-slant to them). Or you could look at buying one of the regional sourcebooks (some of which, like The Paxton Gambit, double as campaign jumpstart kits). Either way you’re on firm ground. I have yet to buy a Dream Pod 9 product that has come anywhere near to disappointing me – even their Character Compendium is an intriguing, exciting product for god’s sake! How do you pull that one off?

But the most original aspects of the Heavy Gear product line (in my opinion) are the storyline books and the Timewatch system. To understand why I feel this way you must first understand why I get frustrated with many other roleplaying game lines – such as Trinity or Fading Suns. While I feel both of those games are some of the strongest competition to Heavy Gear’s title as reigning champion of setting design, those settings are damnably difficult to keep up with. Trinity, for example, requires you to purchase adventure supplements in order to keep up with the developments of the world with any cogent completeness. Another excellent example of this trend is Shadowrun, a campaign setting which has developed through several years of “game time” and which intrigues me deeply, but which will never be able to attract much of my money because trying to buy enough product to untangle what the setting is and where it has been is simply too gargantuan a task for me.

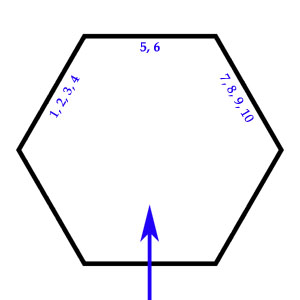

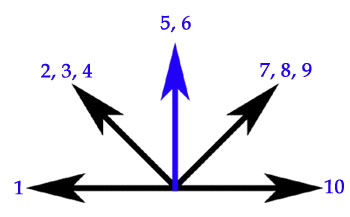

Not so with Heavy Gear (which is to Shadowrun what X-Files is to Babylon 5; both have over-arcing storylines, but only one was worked out in advance… and it shows). First, each product (with one exception where they screwed up) has a date printed on the backcover: the cycle in which the product is set. This simple innovation (known as the Timewatch system) seems simple and obvious, but it is has never been done before. It means that it is possible to figure out when each product is set in the timeline of the setting with a simple glance – you don’t have to wonder, as you stare at a shelf full of product, which ones you should buy first in order to coherently understand the development of the fictional world. You know right off the bat.

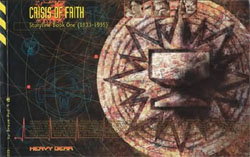

The second element which makes Heavy Gear better than Shadowrun or Trinity, however, are the storyline books (of which Crisis of Faith is the first – see I’m going to get to an actual review of this product eventually). The storyline books cover the major developments in the meta-story of the world over the course of a couple of cycles (the Terranovan equivalent of years). This means that you don’t have to buy, for example, the campaign sourcebook The Paxton Gambit (which might be of negligible or nonexistent use to you) to know about the BRF uprising in Peace River in TN 1935; it will be summarized in the second storyline book (Blood on the Wind) just as the events in the campaign book The New Breed are summarized in Crisis of Faith. Other games have occasionally issued updates or new editions of products, but nothing of this methodical nature. In addition the meta-story of Heavy Gear is like that of Babylon 5 (as noted above) – it was worked out in advance and as a cohesive whole, instead of merely being thrown together as things develop. If some development is hinted at and then carried out later it isn’t because someone had a really cool hint and them somebody else had to ad hoc a solution to it, it’s because the guys down at Dream Pod 9 are really on top of the ball. (The closest I’ve seen anyone else come to this currently is Andrew Bates and Trinity — I heartily encourage him to embrace the storyline book concept from Dream Pod 9 in developing the very intriguing meta-story he is developing there.)

I could go on and on about other brilliancies in the design of the Heavy Gear product line (such as the chesspiece system which tells you at a glance how important DP9 NPCs are to the storyline – allowing you to gauge how much freedom you have in manipulating their lives in your own campaign), but instead I’m going to fulfill my obligation to you and start talking about Crisis of Faith in particular now that you understand the design philosophy which gave it birth.

As I mentioned above, Crisis of Faith is a masterpiece. It also has the potential of being a very misunderstood one.

Specifically, Crisis of Faith can be misunderstood due to its size and due to its content. The first is simple to understand. Like Making of a Universe (a behind-the-scenes look at the development of the Heavy Gear setting and reviewed by myself elsewhere on RPGNet), Crisis of Faith is a half-sized, 112 page book. It simply looks small on the shelf and the fact that it is no cheaper than your average roleplaying product made it look skimpy for the dollar value. Personally I have no problems with this format – particularly since it allowed the inclusion of multiple full-color sections (more on the art below).

The second misunderstanding arises because, quite frankly, this book doesn’t have any immediately applicable usefulness in a roleplaying (or tactical) campaign. Your average sourcebook gives you floorplans or NPCs or something of immediate, tangible use. Crisis of Faith gives you a narrative of events. This has led some to ask, “What good is it?”

Those of you who have read my review of Making of a Universe have probably already figured out where I’m going with this – in short, Crisis of Faith is being judged as something which it is not. Like attempting to judge your daily newspaper in terms of how well it succeeds at being the Great American novel, judging Crisis of Faith as a traditional roleplaying sourcebook is a waste of time. Crisis of Faith attempts to do two things, and it does these things very well:

First, as detailed above, it is primarily useful to the roleplayer or tactical player by providing a narrative of events transpiring in the setting of the Heavy Gear game in a single resource – meaning that you don’t have to buy every product released for the game in order to keep up with the major developments in the world as a whole. The storyline books (along with Life on Terra Nova) free you from that necessity, allowing you to pick and choose the products you need to buy (as much as you “need” to buy any form of entertainment). Naturally if you want a more comprehensive look at a particular event or a particular location then you buy the applicable sourcebook. The key here is that Crisis of Faith (and its sequels) means that you can keep track of the world without having to religiously deposit your weekly paycheck at the hobby store in order to keep up with every release. This is a good thing in my opinion. (The only flaw in this plan is that the Heavy Gear setting is so fantastic that it can prove addicting – forcing you to buy all the products anyway. Oh well. That’s a flaw I, for one, can live with.)

The second function of Crisis of Faith, however, is to tell a good story. The design team down at Dream Pod 9 have realized the simple truth that roleplaying games provide a medium for telling stories in a way which no other medium does – both at the meta-level and at the personal level. At the meta-level the story is the comprehensive development of the world. At the personal level the story is that of the particular PCs. Both stories by themselves (if the particular campaign in question is a good one) can be enthralling and entertaining, but when you weave them together (the personal story taking place in the backdrop provided by the rich, evocative, intriguing meta-story) you have a dynamic process taking place.

And the story being told by Dream Pod 9, and as epitomized in Crisis of Faith, is one of the best. Intrigue, power, politics, war, love, murder, mayhem. You name it and Heavy Gear has got it.

And if that’s all there was to it, Crisis of Faith would already be one of the classics in this industry. But I have yet to deal with another pillar of strength in the Heavy Gear: The Artwork.

[ A brief aside: Heavy Gear is a game seemingly possessed of no weaknesses and excellence in everything. No other line of games in the history of this industry can boast of such a consistent level of quality throughout their entire product line. Usually you can find, even in the best of games, some throw-away product or another where the writing or the art or the basic concept simply wasn’t all that strong. Not so Heavy Gear (or any other Dream Pod 9 product). The strength of their product methodology and their writing has already been dealt with, now let’s look at the artwork. ]

Quite simply no bad artwork has ever appeared in a Dream Pod 9 product. Ever. And that’s a pretty impressive thing considering the dozens of products they’ve produced and the hundreds of illustrations which accompany each one. Quite simply this excellence can be ascribed to Ghislain Barbe. His style for Heavy Gear has been heavily influenced by anime and this has led, occasionally, to the mislabelling of the game as an “anime game”. It isn’t. It is, however, superb – you merely have to flip through any Dream Pod 9 product to see that. It’s simple line art which is crisply inked and then colored by computers (even when the artwork is produced in black and white for the actual book), producing a rich depth to every piece.

The reason I bring this up is that Dream Pod 9’s products are the most visually dynamic and consistent products in the industry ever. And Crisis of Faith is, quite simply, the best of the best.

(To fully appreciate this you should note that Dream Pod 9 “throws away” artwork which most companies would give their left arm’s for by making them smaller on the page in order to produce a visually rich and dynamic whole. Crisis of Faith is an excellent example in which almost every page has three small illustrations (smaller than my thumbnail) in the upper corner – each of which directly reinforces the text. Some of these pieces are recycled from other works, but most of them are originals created specifically for Crisis of Faith.)

Every page in Crisis of Faith shows a brilliancy of lay-out and artistic design which, if everyone else in this industry possessed only 1/10th as much skill, would improve product quality exponentially. Unlike many “artistic designs” almost no element on the page is there merely for the sake of its own existence. Despite that simple utilitarian elements (page numbers, the date of the material being discussed, the line which separates the columns) are beautifully blended into a powerful whole in a masterful display of raw talent. Then there are the color sections, which you can just stare at for extended periods of time.

Did I mention that the last six pages contain a surprise, cliff-hanger ending so shocking that you will be begging for more?

So, to sum up: Crisis of Faith is part of the best game line in existence today. Crisis of Faith is the first in a series of “storyline books” which, if there is any justice in the world, will revolutionize the way in which game settings are developed in this industry. Crisis of Faith tells one of the best stories ever created, taking advantage of the full potential the roleplaying medium has to offer. Crisis of Faith is quite possibly the most visually dynamic and powerful roleplaying product ever designed. Crisis of Faith is one of the best roleplaying products ever. Period.

I know I’ve said it before (and I will undoubtedly say it again), but if you aren’t involved in Heavy Gear you’re missing out on one of the best things this industry has ever had. If you haven’t already done so, go out and buy the second edition of the rulebook, the second edition of Life on Terra Nova, and Crisis of Faith. You won’t be disappointed.

[ One final note: You should read Crisis of Faith before reading the second edition of Life on Terra Nova. This is due to the biggest mistake Dream Pod 9 has ever made, which is detailed in my review of the second edition of Life on Terra Nova elsewhere on RPGNet the Alexandrian. In short if you don’t read Crisis of Faith first the ending will be spoiled. (But then again, if you paid attention to the Timewatch system you’d already know that – since the second edition of Life on Terra Nova takes place in TN 1935, the cycle in which Crisis of Faith ends. ]

Style: 5

Substance: 5

Author: Dream Pod 9

Company/Publisher: Dream Pod 9

Cost: $29.95

Page Count: 112

ISBN: 1-896776-21-3

Originally Posted: 1999/04/13

For an explanation of where these reviews came from and why you can no longer find them at RPGNet, click here.

In general, you can either navigate through the wilderness by landmark or you can navigate by compass direction.

In general, you can either navigate through the wilderness by landmark or you can navigate by compass direction.