(This paper was first presented at the 49th Annual Midwest Archaeology Conference in October 2003. It contents were classified TOP SECRET two days later. It has been supplemented below with more recent findings. I would not release it to the public now if I did not fear that my life was in imminent danger. I no longer believe that those attempting to prevent the dissemination of this information at acting in the best interests of anyone other than themselves. –JA)

I have come to this conference to discuss several recent discoveries in a series of digs outside the city of Basra in Iraq. These digs, primarily centered on some of the oldest ruins of ancient Babylon, were funded largely by the BSAI and carried out during the spring and summer of last year. Most important among the discoveries made during these expeditions were a series of pottery shard inscribed with characters from a previously unknown language. To find such a system of writing, placed in such close proximity to Babylonian artifacts, was a nearly unprecedented discovery.

I had originally hoped, in scheduling this presentation, to be able to offer a much more authoritative reporting of the pottery shards’ exact nature, provenance, and the like. Unfortunately, the shards were entrusted to the National Museum of Iraq in order to carry out spectroscopic cans and carbon dating. The shards have now been reported as lost among the many artifacts looted from the National Museum in April of this year. Fortunately, it has been reported that several color slides and other documentation regarding the shards has been preserved, although it has proven impossible to retrieve that information due to the war.

I have, however, retained my own notes as they were taken during the original expeditions. While a poor substitute indeed for the rare wonder which may be felt in viewing the ancient shards themselves, these notes should prove sufficient to at least familiarize you with the material we discovered.

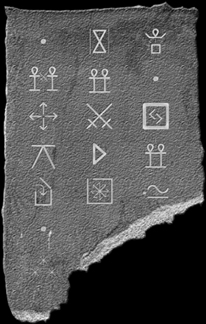

The original find consisted of four distinct and complete symbols on four separate pottery shards:

Other partial inscriptions, stylistically similar to these symbols, were also found in the same location, although none so complete that they could be identified or reconstituted. Structurally these images obviously suggested a pictographic design — possibly directly ideogrammatic or perhaps alphabetically derived from an ideogrammatic construction. But without any meaningful context, it seemed as if these symbols would remain hopelessly mysterious.

However, several weeks later a single large shard was discovered. Several more of these symbols were found. But, more importantly, the symbols were accompanied by what appeared to be a literal translation written in Akkadian cuneiform. It appeared that the shard recovered constituted one complete and one partial sentence, suggesting that the inscription may have originally been part of a larger whole. The language was written in a top-to-bottom, left-to-right format with each sentence comprising a single column of symbols. It can be roughly translated as follows:

|

WE |

|

??? |

|

ARE NOT |

|

THE |

|

ALONE |

|

SECRET |

|

IN |

|

OF THE |

|

THE |

|

|

|

MANY STARS |

|

|

The first word in the second sentence, given its symbolic resemblances in other ideogrammatic languages, could be considered “defend” or “protect”, rendering a full translation of this fragment to read something to the effect of: “We are not alone among the many stars. Defend the secret of the–”

To date, this represents the full scope of our discoveries regarding this strange new script and language. I present them here today in the hope that others may have encountered similar symbols in their independent research or that, failing such unlikely fortune, that fresh eyes may bring some elucidation to this subject.

The rest of my presentation today will discuss other aspects our expedition and the context in which these fragmentary artifacts were found.

BENEFACTOR STONE PROJECT

Such were my findings — meager as they were — in the autumn of 2003. I was contacted two days later by [TEXT DELETED]. My research was confiscated and I was informed that all information regarding these symbols had now been classified. I was prohibited from speaking about it. The original material lost during the looting of the National Museum was never, to my knowledge, recovered.

But I remained fascinated by what we had found. And so I kept my eyes and ears open, hoping to find some new scrap of information that might shed light on these symbols and their true history. But if any new discoveries were being made, no news of it reached me.

Then, in the summer of 2005, quite by accident, I made a new discovery. In the July 1954 issue of the American Journal of Archaeology I found an article discussing several artifacts recovered during an expedition in the Andes mountains of Peru. Among these artifacts was a “small disc with a metallic triskelion in the center and strange ideograms along the edge”. Dubbed dramatically the “Mystery of Piedra de las Acianos”, it was treated in the article as little more than a curiousity. But several of the symbols from the edge of the disc — selected seemingly at random — were detailed in accompanying illustrations. Several of these symbols were exact duplicates of the symbols we had discovered outside of Basra!

I immediately set about trying to track down the current whereabouts of the disc. This proved to be surprisingly difficult, but after much effort I eventually discovered that the disc had recently been transferred from a Peruvian museum to a small research group in the United States known as the Benefactor Stone Project. I was unable to determine what, exactly, the Benefactor Stone Project was or why such an unprecedented transfer had taken place.

It seemed as if the trail would go cold and I would, once again, be denied any satisfactory answers. But then, quite suddenly, the Benefactor Stone Project found me: I received a package in the mail with no return address. Inside was a plaster reproduction of several symbols in what appeared to be three distinct sentences. There was also a written request to “provide whatever insight and translation may be possible”, along with instructions detailing how anonymous e-mails could be sent to a particular address.

This was only the first of many correspondences. It quickly became apparent that I was not the only one working with material apparently drawn from the “Mystery of Piedra de las Acianos” (which we were now referring to as the “Benefactor Stone”). The Benefactor Stone Project began to disseminate “confirmed translations” of various symbols, apparently derived from the work of other researchers. It also became clear that, while the samples gave enough context to make meaningful work possible, there was a definite desire to conceal the full text of the Stone.

THE GARRIOTT TRANSLATIONS

Work was slow at first. My own knowledge, derived from the Akkadian translations I had found in 2002, helped considerably in giving context to the material I was shown.

But another breakthrough came in March 2006. I received an e-mail from Dr. R. Garriott, a professor of linguistics and archaeology at Columbia University. He claimed to have discovered my e-mail as a “fellow collaborator of the BSP”, although he said that “it would be better if you did not ask how I came by such information”. He was apparently writing in order to share three unique discoveries:

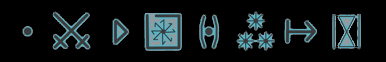

First he provided pictures of an obelisk he had discovered with a complete sentence of alien text intact:

Most astonishingly, Garriott asserted a translation for this sentence (which contained many symbols which had been previously unidentified): “This sentence means literally: “A long — time ago [time in the past] — our — civilization — grew — upon — a — planet — that was [in the past] — a far — journey — into — the stars.” Or, more succinctly: “Long ago our civilization grew upon a planet that was a far journey into the stars.”

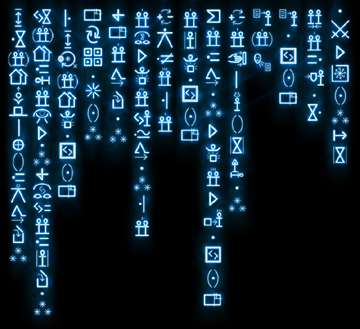

Second, Garriott offered another short sentence without any explanation of where he had gotten it from:

Regarding this sentence he said this:

In this language dots are used to mean specificity, so that first dot is the word “the”. The second symbol of crossed swords (again most advanced cultures likely fought with sticks, then blades), means “battle” (or war), the triangle pointing to the right means “for” (or to), if it had pointed left it would have been “from”. The next symbol of radiating arrows in an enclosure is the symbol for “control”. The radiating arrows are the symbol for “chaos” and the nearly closed box around it is the symbol for “enclosure.” Thus bounded or contained chaos is “control”. Parenthesis around a symbol means possessive. So parenthesis around a stick figure man would mean “his,” in the next symbol the dot inside of parenthesis means “of the.” The next symbol is a collection of three “star” symbols, which is the word “cosmos” (or universe). There are many symbols which incorporate arrows to imply direction, going, stopping, etc. The next symbol is an arrow leaving a boundary line that means “begins.” The final symbol is built by the symbol for “time” bounded on both sides by vertical lines. Time with a dot to the right would mean “future” time with a dot to left “past”. In this case time between these boundaries means “now”.

And thus: “The battle for control of the cosmos begins now!”

Dr. Garriott was frustratingly vague in where this material had come from and how he had obtained or derived his translations. But when I compared his material to the material already in my possession, I found it consistently providing what appeared to be useful and accurate context.

I suspect I was not the only one to receive this material from Dr. Garriott. The stream of “confirmed translations” coming from the BSP multiplied rapidly in its wake.

My attempts to contact Dr. Garriott directly proved fruitless. Columbia University listed Dr. Garriott as being on temporary leave while researching with the D.G. Archaeology Group.

Several weeks later, however, I received another package from Dr. Garriott, this one containing only a single picture of an obelisk similar to the one he had discovered previously:

Garriott provided no translation of this text, although some guesses can be made in that direction based on the material we had already discovered:

SYMBOL 1: The symbol for “battle” or “conflict” modified by the dual-lines which modify “time” into “now” and “person” into “alone”. This suggests, perhaps, “fight” or “attack”.

SYMBOL 2 — WE

SYMBOL 3 — JOURNEY

SYMBOL 4 — COSMOS

SYMBOL 5 — FOR/TO

SYMBOL 6 — This symbol appears to be some variety of the symbol meaning “discovery”. Multiple boxes appear instead of a single box. Perhaps this is a way of representing the plural?

SYMBOL 7 — ????

SYMBOL 8 — FOR/TO

SYMBOL 9 — GIVE

SYMBOL 10 — The BSP had independently confirmed the symbol for “energy” (a lightning bolt). In this construction the lightning bolt has been placed inside the “enclosure” (to use Garriott’s terminology) which represents control when surrounding chaos or a secret when surrounding a piece of information. Thus “enclosed energy”.

SYMBOL 11 — ????

Giving us a fragmentary translation of the sentence as: [FIGHT?] [WE] [JOURNEY] [COSMOS] [FOR/TO] [DISCOVERIES?] [???] [FOR/TO] [GIVE] [ENCLOSED ENERGY] [????]

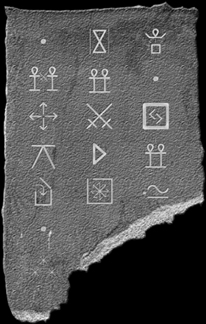

THE TABLET

The next major discovery was apparently the result of a BSP-funded study to Tulum on the Yucatan peninsula that took place during March of this year. Why anyone would think to look for new discoveries in what has, essentially, become a tourist trap astonished me. (Although now I hypothesize that, perhaps, some unique information gifted that expedition with unusual insight into fresh possibilities.) Nevertheless, the expedition met with success, recovering a partial tablet containing a remarkably complete fragment of the ancient script:

The discovery of this tablet helped confirm how much progress we the diverse efforts of the BSP had made, as we were able to translate the tablet in its entirety almost immediately upon its discovery:

SENTENCE 1: [THE] [FOE] [DISPERSES] [FAR] [INTO] [THE] [COSMOS]

SENTENCE 2: [NOW] [WE] [BATTLE] [TO] [CONTROL] …

SENTENCE 3: [DISCOVER] [THE] [SECRET] [WE] [MIGHT HAVE] …

This translation reveals several basic grammatical structures which have been found throughout these ideograms:

(1) The specificity indicated by the symbol a single dot, and the use of that glyph to indicate past, present, and future tense (as can be seen in the modification the glyph for “might” into “might have” — if the dot had been on the opposite side of the glyph it would have indicated “might be”).

(2) The function of the square as a means of indicating an “enclosure” — as seen in the symbol for “secret” (where it contains “what is”); the symbol for control (where it is in the process of containing “chaos”); and the symbol for “into” (where an arrow indicates the action of putting something into the enclosure).

(3) The vaguely humanoid figures used to indicate relationships, groups, and individuals.

In general, the fact that complex symbols are generally made by modifying simpler symbols using a few basic constructions has made understanding this language painfully simple, almost as if it had been specifically designed for others to learn and understand its meaning.

But this tablet raised twice as many questions as it helped to solve: How had a language originally discovered in the fertile crescent founds its way, virtually unaltered, to an ancient Mayan ruin?

THE MESSAGE

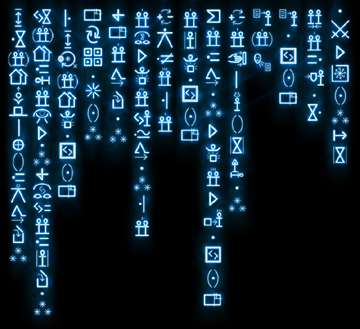

Now we come to the most recent chapter in this strange saga — a saga which has brought no peace to my mind or to my dreams. The BSP has supplied me with a message of unknown origin. (It clearly does not originate with the circular disc which is still kept so jealously in their possession.) It is the most complete text I have ever seen in this language which has beleaguered me for more than half a decade, and the ease — nay the eagerness — with which the BSP has parted with it makes me think that there is some quiet desperation in their efforts to decode it as quickly as possible.

Between the work of Dr. Garriott, the confirmed symbols I have received from the BSP, and my increasingly subconscious — and oddly disturbing — understanding of these ideograms, I believe I have successfully translated this text. The message it reveals is but one part of the reason I seek to communicate these findings to the wider world. I fear what the wide dissemination of this knowledge may mean, but I am possessed of the firm conviction that what I do — though it may ultimately end in my own discrediting or even death — is of the utmost important.

To begin, let us look at what I knew for a certainty as I came to this text. (It should be noted that, oddly, the first and last sentences are, in fact, those found and translated by Garriott.)

KNOWN TRANSLATION

SENTENCE 1: [LONG] [AGO] [OUR] [CIVILIZATION] [GROW] [UPON] [A] [PLANET] [THAT] [WAS] [FAR] [JOURNEY] [INTO] [MANY STARS]

SENTENCE 2: [???] [OUR] [CIVILIZATION] [WAS] [YOUNG] [WE] [LOOK] [FOR/TO] [THE] [MANY STARS] [AND/WITH] [???] [WHAT IS] [WE] [WAS] [ALONE] [INTO] [MANY STARS]

SENTENCE 3: [AFTER] [LONG] [???] [OUR] [CIVILIZATION] [DISCOVER] [THE] [SECRET] [OF THE] [???]

SENTENCE 4: [???] [???] [???] [THE] [???] [OF THE] [MANY STARS]

SENTENCE 5: [AND/WITH] [???] [WE] [JOURNEY] [INTO] [THE] [MANY STARS]

SENTENCE 6: [WE] [???] [FOR/TO] [DISCOVER] [???] [WHO] [MIGHT HAVE] [JOURNEY] [THE] [MANY STARS] [BEFORE] [WE]

SENTENCE 7: [???] [THERE] [WAS NOT] [???] [BEFORE] [WE]

SENTENCE 8: [WE] [ALONE] [DISCOVER] [THE] [SECRET] [OF THE] [???]

SENTENCE 9: [???] [WE] [WAS] [JOURNEY] [THE] [MANY STARS] [FOR/TO] [DISCOVER] [???] [FOR/TO] [GIVE] [THE] [SECRET] [OF THE] [???]

SENTENCE 10: [???] [WE] [???] [A] [???] [THAT] [NOW] [???] [THE] [MANY STARS]

SENTENCE 11: [???] [OUR] [???]

SENTENCE 12: [???] [THE] [SECRET] [OF THE] [???]

SENTENCE 13: [???] [WE] [WILL] [???] [THE] [FUTURE]

SENTENCE 14: [THE] [BATTLE] [FOR/TO] [CONTROL] [OF THE] [MANY STARS] [BEGINS] [NOW]

WORKING THINGS OUT

SENTENCE 1: This sentence is known in full, thanks to Dr. Garriott’s work.

SENTENCE 2: There are two unknown symbols in this sentence. The first of these is a compound symbol in which we do, in fact, know both constituent parts: The first part means literally “what is” and the second part means “time”. We have, in fact, seen this construction in some of the symbols known to the BSP. In a similar construction the compound of “what is” and “person” the symbol is known to mean “who”. Thus we can conclude that, in this case, the compound means “when”.

In the case of the second unknown symbol, we have another compound symbol, but in this case we do not know the constituent parts in full. Once again, however, we have the symbol for “what is”. Given the relatively humanoid quality of the ideograms in general and the context of this compound in other situations, I feel comfortable in guessing that this symbol is being literally embedded in someone’s forehead — a traditional expression of thought. Thus we have a symbol which might be literally understood as “thinking on what is” or “wondering”.

SENTENCE 3: There are two unknown symbols to be found in this sentence, as well. The basic form of this ideogram is “year”, but there is an additional “x” in the lower right-hand corner. It is my belief, particularly given its context here, that this “x” is meant to denote a plural form — thus, “years”. (NOTE: This has recently been confirmed by the BSP through study of other sources.)

The second symbol here is literally a diagram representing the mathematical Golden Ratio — also known as the Golden Logos. We have seen this ideogram elsewhere, but are uncertain of exactly what it is being used to refer to. For the moment we have taken the liberty of translating it simply as “logos”, allowing the context in which it is found to speak for itself.

SENTENCE 4: The first unknown symbol here is, again, “logos”. We’ll come back to the second, but the third is a variant on known symbols for “none” (four empty boxes), “few” (one box filled), “some” (two boxes filled), and “many” (three boxes filled). It would seem to be a safe assumption that, with all four boxes filled, we are looking at an ideogram for “all”.

The fourth unknown symbol is that for a “star” with a hole in the middle. This might be blackhole, but it seems that “wormhole” would be a better translation given its context in a later sentence (as we shall see).

Thus the sentence may be read: “Logos ??? all the wormholes of the cosmos.” By context it would appear that the symbol which remains must be some sort of verb. The two arrows (representing action) revolving into each other would seem to indicate a cycle of some sort, but “Logos cycles all the wormholes in the cosmos” makes little seeming sense. But consider, for a moment, how often “creation” is referred to as a cycle in our primitive philosophies, religions, and mythologies. Thus I propose that “creation” is an appropriate fit here (although I am fully willing to admit that it may not be a perfect fit).

SENTENCE 5: “Logos” is the only symbol we do not know for certain here.

SENTENCE 6: Again we have the ideogram suggestive of “thought”, but this time the thought imbedded in the forehead is that of “future”. It is literally a “thought for the future” or a “thought of the future”. Perhaps it may mean hope or perhaps it may mean a plan, but in essence the distinction between the two is nearly meaningless in this sentence.

The second unknown symbol in this sentence is a variation on a symbol which means “we” (with a single line above it). I will suggest, given this relationship and its context in this sentence, that this usage may mean “they” (or, more generally, “others”).

SENTENCE 7: The first unknown symbol here, with its actions between the positive and the negative, suggests an opposing charge. It would seem to mean literally “opposing” or “opposite”, but is most likely used here in the sense of “but” or “on the other hand”.

The second unknown symbol is much simpler to intuit: We know the sign for “is not” (the equal sign with a line through it) and we know the dot preceding it renders it into the past tense of “was not”.

SENTENCE 8: Once again, “Logos” is the only symbol we do not know for certain here.

SENTENCE 9: Here we find a symbol which seems to gouge the symbol meaning “for” or “to” out of the symbol for “contain”. I have an intuitive sense that this symbol means “therefore” or something akin to it. The symbol for “others” is the second unknown symbol in this sentence and “Logos” is the third.

SENTENCE 10: This is the most difficult sentence to unravel. The first symbol we have established as “but”, but this leave three symbols unaccounted: A hand with arrows (indicating action) pointing towards an indeterminate object; the symbol for a person with an unknown symbol above its head; and a symbol for one person (with upraised arms standing over the figure of another person laying down.

Let us start with this last unknown symbol: The symbol of a person with their head pointing towards the left indicates “youth” or “infant”, as we have seen. Given the positional grammar inherent in many of these ideograms, it seems likely that the symbol of a person with their head pointing in the opposite direction would have the opposite meaning, indicating either “age” or “death”. In either case, the prostrate position indicates a position of weakness while the other figure seems somehow triumphant with its upraised arms. Would it be absurd to suggest that this symbol means either “threaten” or (perhaps more likely) “conquer”?

Thus we have a sentence reading: [BUT] [WE] [???] [A] [???] [THAT] [NOW] [THREATEN] [THE] [MANY STARS]

But we <something> a <something> that now threaten the cosmos.

They were exploring. What natural consequences could there be from exploring? Finding. Searching. Reaching. Contacting.

This last seems most likely, for the symbol of a person as the other known symbol suggests a sentient being they could have contacted. And the ideogram of a hand performing an action towards an object could be to “contact” that object.

Thus we have: [BUT] [WE] [CONTACT] [A] [???] [THAT] [NOW] [THREATEN] [THE] [MANY STARS]

What did they contact? Other compound symbols using the single person with a symbol above their head are known: For example, the symbol for “father” is a single person with a carat above their head.

Perhaps some clue can be garnered from the nature of that symbol: It resembles an inverted omega. Certainly other characters within the ideograms have been known to resemble Greek letters. Is it possible that, as the omega literally means “the end”, an inverted omega could mean “new”? A “new person”? A “new people”?

Or possibly this symbol indicates another relation (other than father). But what relationship? Cousin perhaps?

Or perhaps this symbol is meant to symbolize an all-inclusive category. Could it mean simply “race”?

The subtlety here is lost due to lack of context, but we know from other research that the people who created these ideograms feared people known as the “Bane”. Given the context of the entire sentence it does not seem unlikely that, whatever the precise meaning of this symbol, that it refers to the Bane.

Thus: But we contacted a race [the Bane] that now threatens the cosmos.

SENTENCE 11: The symbol of the small square with three lines is a nearly universal representation of writing in primitive ideogrammatic languages. Writing is, literally, the embodiment of knowledge. Thus, in the first ideogram in this sentence, the knowledge is literally being placed into a person (suggesting a meaning of “learn”). In the last, the knowledge appears to be coming out of the person’s mouth (suggesting a meaning of “teach”).

SENTENCE 12: Here, again, we see the symbol for “learn” and the symbol of “logos”.

SENTENCE 13: The symbols of two people are shown coming together using the familiar action arrows, clearly indicating a meaning of “together”. The shield in the other unknown symbol suggests some form of protection, while the arrow indicates an action — thus “defend”.

SENTENCE 14: And this is the other sentence for which Dr. Garriott has given us a complete translation.

IDEOGRAM TRANSLATION

Thus the complete message can be understood (ideogram-by-ideogram) as:

SENTENCE 1: [LONG] [PAST] [OUR] [CIVILIZATION] [GROW] [ON/UPON] [A] [PLANET] [THAT] [WAS] [FAR] [JOURNEY] [INTO] [MANY STARS/COSMOS]

SENTENCE 2: [WHEN] [OUR] [CIVILIZATION] [WAS] [INFANT] [WE] [LOOK] [FOR/TO] [THE] [MANY STARS/COSMOS] [AND/WITH] [WONDER] [WHAT IS] [WE] [WAS] [ALONE] [IN/INTO] [THE] [MANY STARS/COSMOS]

SENTENCE 3: [AFTER] [LONG] [YEARS] [OUR] [CIVILIZATION] [DISCOVER] [THE] [SECRET] [OF THE] [LOGOS]

SENTENCE 4: [LOGOS] [CREATE] [ALL] [THE] [WORMHOLE] [OF THE] [MANY STARS/COSMOS]

SENTENCE 5: [AND/WITH] [LOGOS] [WE] [JOURNEY] [IN/INTO] [THE] [MANY STARS/COSMOS]

SENTENCE 6: [WE] [PLAN/HOPE] [FOR/TO] [DISCOVER] [OTHERS] [WHO] [MIGHT HAVE] [JOURNEY] [THE] [MANY STARS/COSMOS] [BEFORE] [WE]

SENTENCE 7: [OPPOSING STATE] [THERE] [WAS NOT] [OTHERS] [BEFORE] [WE]

SENTENCE 8: [WE] [ALONE] [DISCOVER] [THE] [SECRET] [OF THE] [LOGOS]

SENTENCE 9: [THEREFORE] [WE] [WAS] [JOURNEY] [THE] [COSMOS] [FOR/TO] [DISCOVER] [OTHERS] [FOR/TO] [GIVE] [THE] [SECRET] [OF THE] [LOGOS]

SENTENCE 10: [OPPOSING STATE] [WE] [CONTACT] [A] [COUSIN/RELATIVE/RACE/BANE] [THAT] [NOW] [CONQUER/THREATEN] [THE] [MANY STARS/COSMOS]

SENTENCE 11: [LEARN] [OUR] [TEACH]

SENTENCE 12: [LEARN] [THE] [SECRET] [OF THE] [LOGOS]

SENTENCE 13: [TOGETHER] [WE] [WILL] [DEFEND] [THE] [FUTURE]

SENTENCE 14: [THE] [BATTLE] [FOR/TO] [CONTROL] [OF THE] [MANY STARS/COSMOS] [BEGIN] [NOW]

THE FINAL TRANSLATION

Long ago our civilization grew upon a planet that was a distant journey into the cosmos.

When our civilization was young we looking into the cosmos and wondered whether we were alone in the universe.

After long years our civilization discovered the secret of the Logos.

Logos created all the wormholes of the cosmos.

With Logos we journeyed into the cosmos.

We hoped to discover others who might have journeyed the cosmos before us.

But there were no others before us.

We alone discovered the secret of the Logos.

Therefore we journeyed the cosmos to discover others to give the secret of the Logos.

But we contacted the Bane that now threatens the cosmos.

Learn our teachings.

Learn the secret of the Logos.

Together we will defend the future.

The battle for control of the cosmos begins now!

MAKE OF IT WHAT YOU WILL

After a procrastination of nearly epic proportions, I finally subscribed to GameFly last week. The GameFly queue system is not nearly as elegant as Netflix (since it seems to basically amount to a crap-shoot no matter what priority you actually give the games in your queue), but the result was that Infamous materialized in my mailbox a couple of days ago.

After a procrastination of nearly epic proportions, I finally subscribed to GameFly last week. The GameFly queue system is not nearly as elegant as Netflix (since it seems to basically amount to a crap-shoot no matter what priority you actually give the games in your queue), but the result was that Infamous materialized in my mailbox a couple of days ago.