Did you know that the D&D 5th Edition core rulebooks don’t include an example of a keyed dungeon map?

This is because D&D no longer teaches you how to prep or run a dungeon.

This is a wild thing to think about, and it actually gets weirder the more you think about it. Back in 2020, in Whither the Dungeon?, I pointed out that this had created an entire generation of Dungeon Masters who had, paradoxically, never learned how to master a dungeon. Even the oral traditions which had once passed this knowledge from one DM to another were breaking down, partly because this was actually the end point of a long-term trendline (the dungeon instruction in D&D 4th Edition, 3rd Edition, and even 2nd Edition had grown increasingly anemic) and partly because of the huge influx of new gamers via channels other than playing in someone else’s game over the past decade.

By the end of the 2010s, you could already see the effects of this manifesting in DMs Guild and other third-party adventures: An ever larger number of dungeon adventures were being published without numbered maps; the contents of those dungeons described in haphazard paragraphs which were often little more than a rambling stream of consciousness.

This was bad in its own right, but this degradation of published books was only a reflection of an even deeper rot at casual gaming tables – a malaise invisible to those afflicted, because they didn’t even know what they were missing.

Then, in 2023, Wizards of the Coast published The Shattered Obelisk. As noted in my review, this campaign book included multiple unkeyed dungeons. This, in my opinion, was a red alert: It wasn’t just that Wizards was neglecting to teach basic dungeon design; it appeared that the design team itself was losing the institutional knowledge to design dungeon adventures. (The call was coming from inside the house!)

But maybe this was just a fluke, right?

In 2024, the new Dungeon Master’s Guide was released. Like the 2014 Dungeon Master’s Giude, it failed to include even an example of a keyed dungeon map, let alone any sort of actual instruction in keying a dungeon map or running dungeon adventures. Except it was even wore than that: The new DMG included multiple sample adventures for new DMs, including three dungeon adventures… none of which were keyed: One just said “there are some monsters in there.” Another tried to vaguely describe through words where each encounter was located on the map (e.g., “in a sidecave to the southeast” or “at the north end of the stream”). A third tried to use a broken method of random encounter checks.

So where the 2014 DMG simply neglected to teach new DMs how dungeons work, the 2024 DMG escalated to only showing examples of exactly how you should not design a dungeon. This, in my opinion, was now a five-alarm fire.

All of which brings us, in 2025, to Borderlands Quest: Goblin Trouble, one of the first official adventures for 2024 D&D, released as introductory adventure to promote the upcoming Starter Set: Heroes of the Borderlands.

It’s a dungeon adventure.

It’s unkeyed.

Something is rotten in the state of D&D.

WHERE, OH WHERE IS THIS ROOM?

At this point, many reading this might be thinking, “Well, so what? What’s the big deal?”

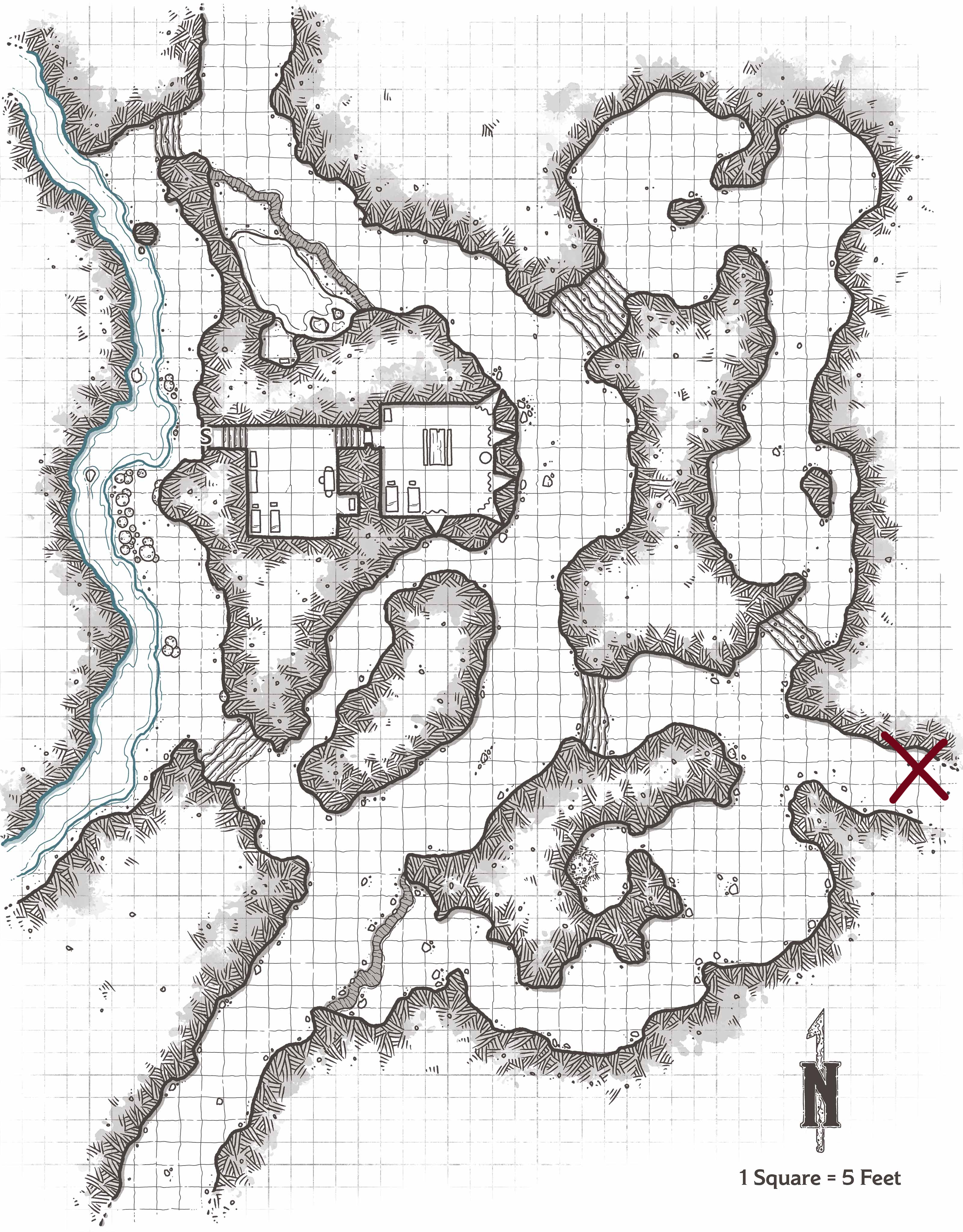

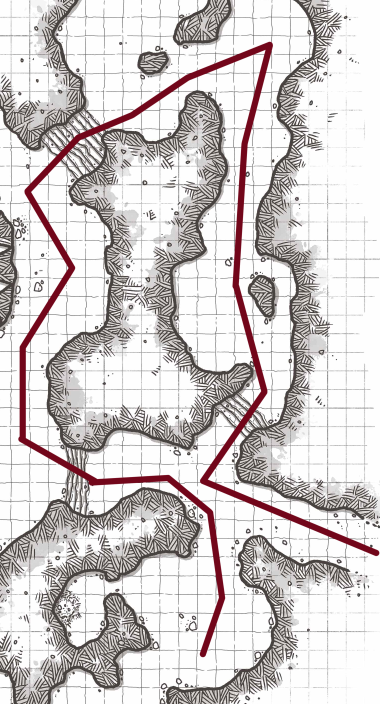

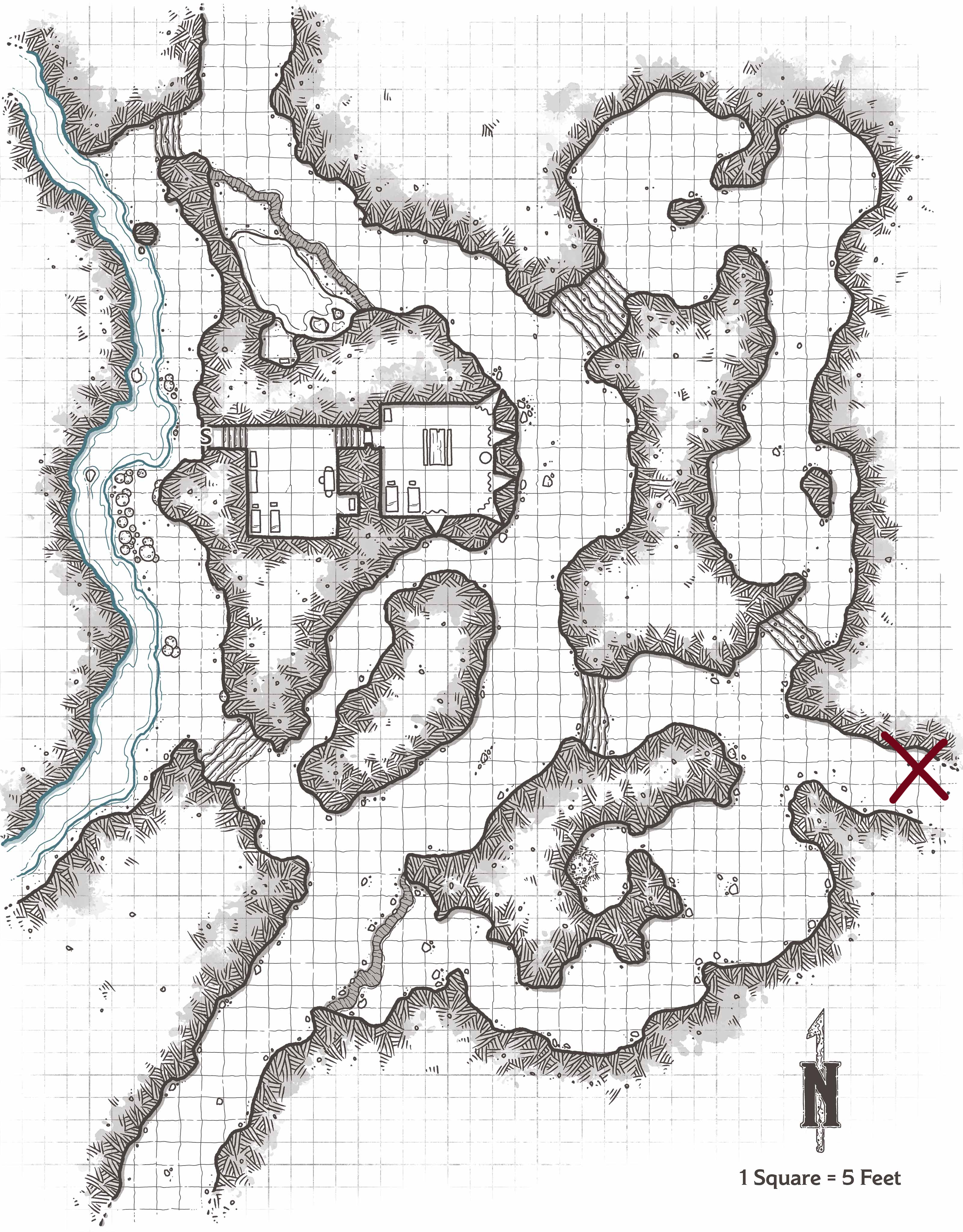

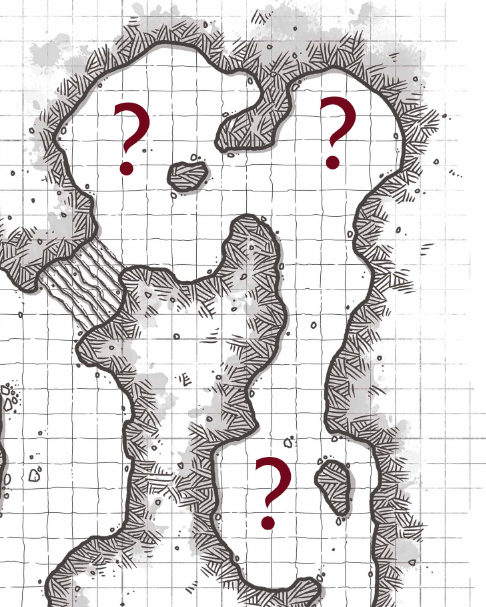

To understand the problem, let’s take a peek at what happens when you try to actually run Goblin Trouble, starting with the PCs following some bandits and “enter[ing] the cave from the eastern edge of the map.” Checking the map, it’s pretty easy to figure out where this is:

It will later turn out that the actual location being described is several hundred feet to the west, but we can let that slide. So far, so good!

But things quickly get more complicated:

From the cave entrance, a passage continues deeper beneath the hills and slopes downward. You travel for several minutes before the passage turns north and leads up a set of natural stone steps. A group of caverns continues out ahead of you.

The ceiling of these caverns is choked with webs, and the footprints you’ve been following continue through these caves. In the center of the floor in the first cave is a human-sized boot.

I’m fairly certain that this is what the boxed text is describing:

But, as you can see, the PCs have moved past a major intersection without the adventure even mentioning that it exists. This is quite strange, but let’s put a pin in that. We’ll come back to it later.

At this point, the adventure describes an encounter with some spider webs and dead spiders… but is this actually where this takes place? It’s unclear. When the PCs went up the stairs, north, and into/through a “group of caverns,” how far did they go exactly? How many caverns are we talking here?

At first it seems like it could be any or all of these caves, but later, after the encounter with the dead spiders is described, we’re told that

The passage continues onwards, taking the characters north for a while, and then switching back south. The caves here are empty, save for some old cobwebs on the ceiling.

Eventually, the characters find themselves on the southeastern side of the map, near some steps that lead into a cavern with an underground stream flowing in it.

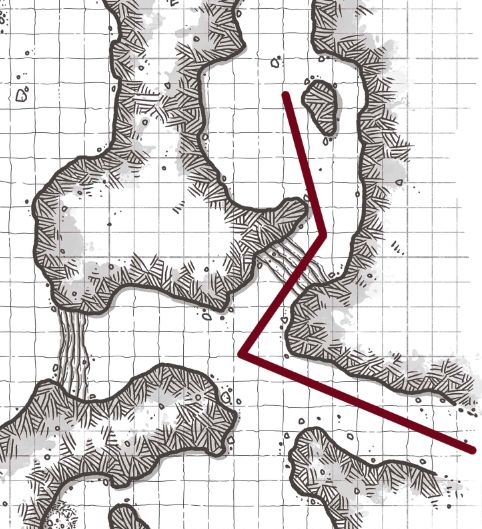

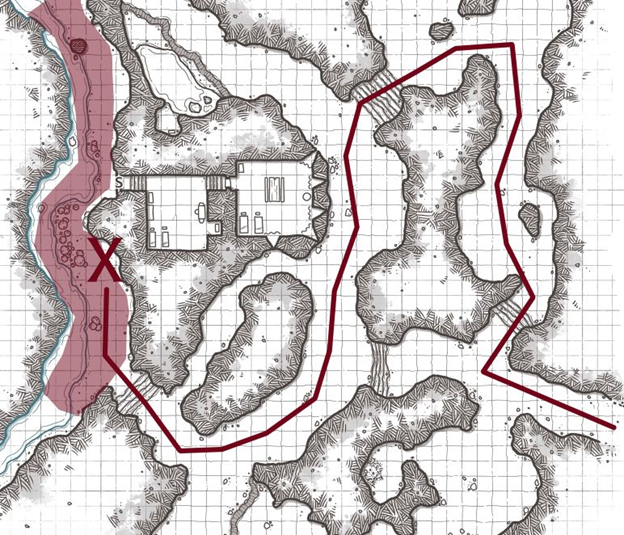

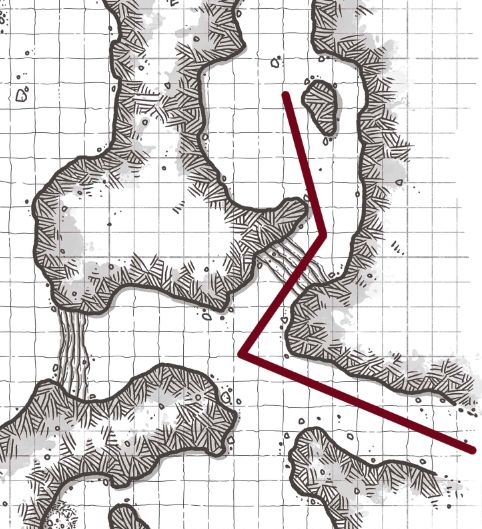

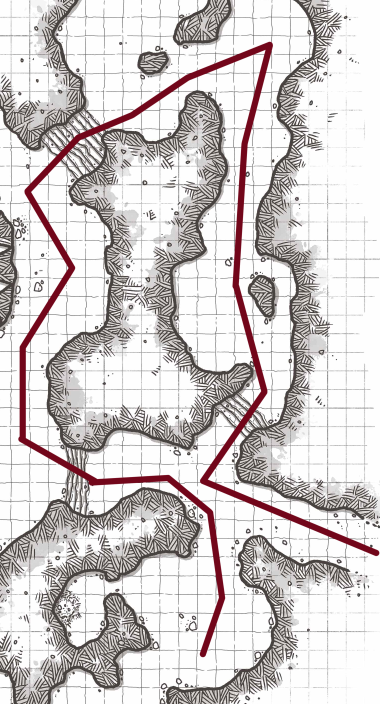

So the dead spiders must have been in the southern cave (so that the PCs could leave it going north). Furthermore, there’s only one cave on the southeastern side of the map, so that must mean that the PCs follow this path:

As we can see, the adventure is once again skipping past several more intersections and the PCs end up… in the cave immediately to the left of where they entered? That’s bizarre.

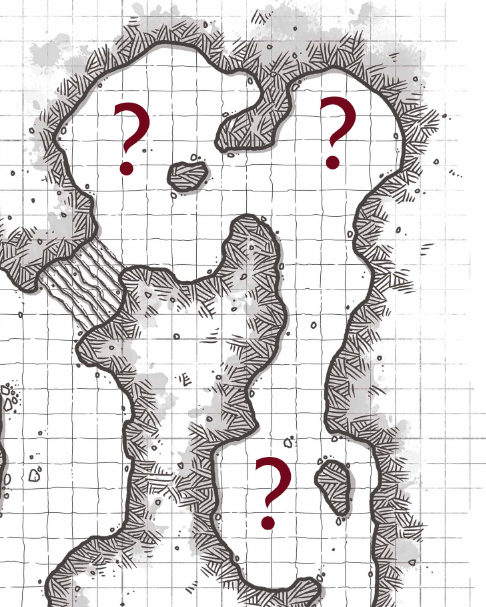

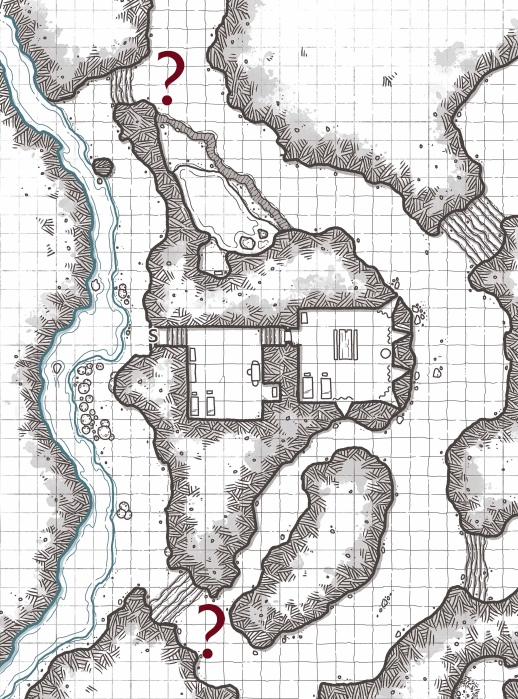

It turns out, though, that this must be a typo. This is supposed to be “near some stone steps that lead into a cavern with an underground stream flowing in it.” The stream is on the other side of the map, so they must mean one of these two locations:

But which one?

I can guess, but there’s no way to actually know.

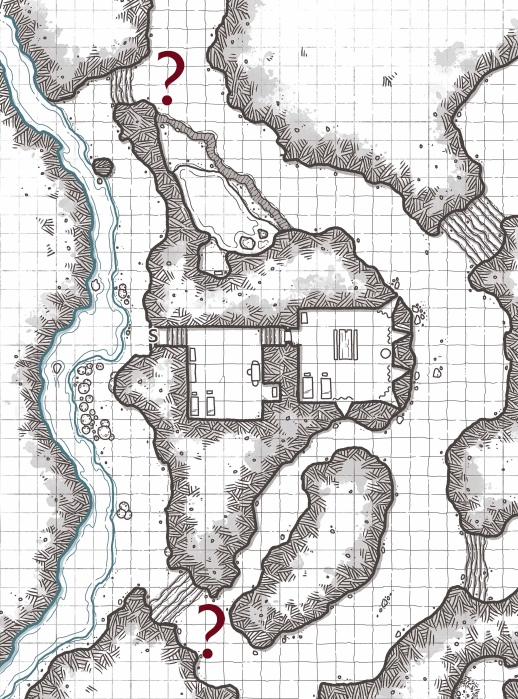

At this point we’re told that the bandits the PCs are following are “in the cavern ahead” and “trying to summon the courage to peek around the corner and see what the goblins are up to.” But what does this mean, exactly?

They must be somewhere in this area:

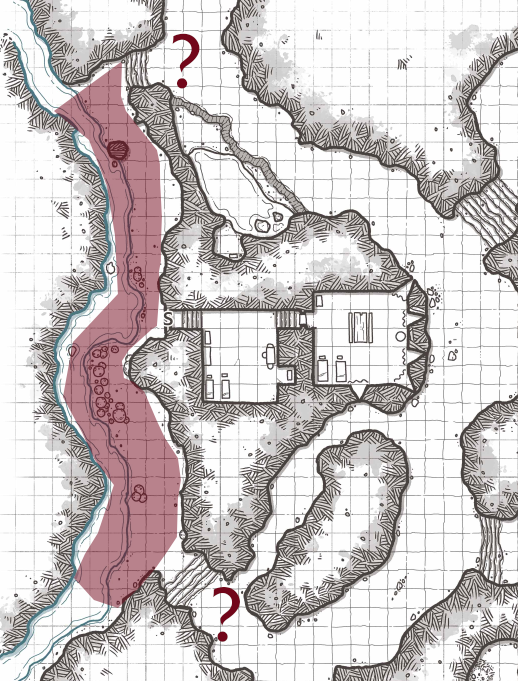

But where’s the corner they’re “peeking around”? Reading ahead, we can figure out that the goblins are hiding inside the secret lair, but the bandits don’t seem to know that. Nevertheless, maybe we can play this as “they look around the corner and are confused to discover a blank wall of stone.”

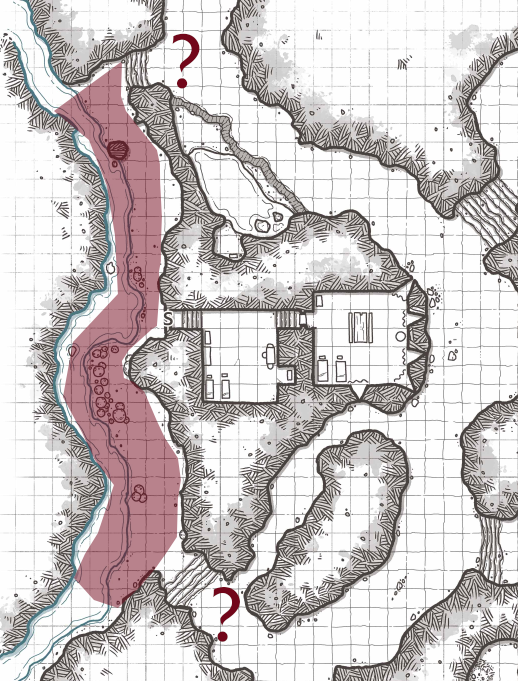

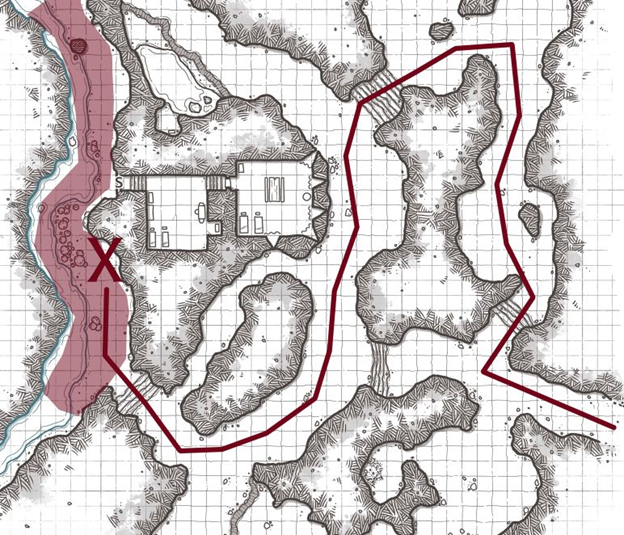

Okay, so “southeast” is probably a typo for “southwest.” And the “corner” must be that outcropping of rock, so the bandits must be standing at the X:

We also know the path the PCs must have taken (which is still bonkers, but let’s stick another pin in that!). We’ve figured it out!

Phew!

…

Just kidding. The bandits can’t be standing there, because several pages later we discover that the goblins have set up a trap in the mushroom patch. This is not, of course, keyed to the map. (Why would it be?) But if the bandits were there, they would have triggered it.

So where ARE the bandits supposed to be?

I have no idea! Good luck, first-time DMs!

CONSEQUENCES

It’s important to understand that this isn’t some fluke. This is what always happens when you try to describe the contents of a dungeon through rambling paragraphs instead of clearly indicating where things are located on the map.

If you think about it, this principle isn’t just limited to dungeon design. It’s a fundamental property of maps. Imagine, for example, if the maps app on your phone just displayed a bunch of unlabeled streets and said, “Turn left somewhere up ahead. I’m sure you’ll figure it out!”

And the problem here isn’t just that you’re being forced to solve a Where Is This Room? puzzle before you can run the adventure. The deeper problem is that, without a proper scenario structure, you’ll end up prepping the wrong stuff. And even if you prep the right stuff, it’ll be organized in ways that make it difficult or even impossible to use at the gaming table.

In truth, what usually happens is that the designer or GM will end up defaulting back to the only structure they have left: A railroad.

And that’s exactly what happens in Goblin Trouble.

The opening advice for the new DM (which is quite good, actually; check out Nerd Immersion’s video that takes a closer look at this) spends a good deal of time talking about the importance of player choice and how players should be driving the action of the adventure. But the very first thing the adventure says is that (a) there’s only one thing the players can do; (b) if they don’t, the DM should tell them what to do; and (c) if that also doesn’t work, the DM should then use their “power to change the world around them to spur them to action.”

Then, as we’ve seen, the rest of the adventure is forced onto a purely linear track: The players can only choose to go forward or backward. Despite a xandered dungeon map, the predetermined narrative simply shuffles them along a track that ignores all opportunities for choice or navigation.

THE KICKER

Goblin Trouble continues in this vein for a while, but then, right near the end, we find this:

The Forge. The makeshift forge in area 4a occupies the spot at the back of the second room.

Area 4a?

This means that, at some point, somebody actually keyed a map. And then somebody else decided to remove the map key and rewrite Goblin Trouble as a nearly incoherent linear railroad.

There’s some nice stuff in Goblin Trouble: The opening GM advice. The texture of the encounters. The roleplaying vs. combat opportunities set up with the bandits.

But it’s fatally sabotaged by a fundamental failure of basic scenario structure and adventure design. I find it particularly alarming that this appears to have been done to an adventure which initially didn’t have these problems, suggesting that there’s something systemically wrong with the development process for adventures at Wizards of the Coast.

It’s a “the call is coming from inside the house” moment and, in my opinion, bodes ill for future Wizards of the Coast adventures.

And, frankly, for the hobby.