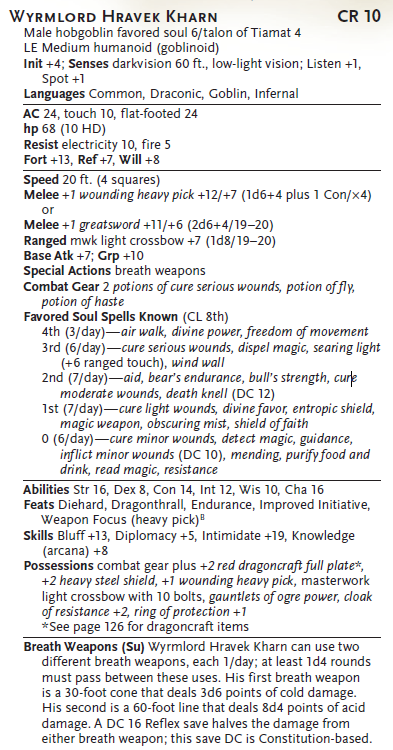

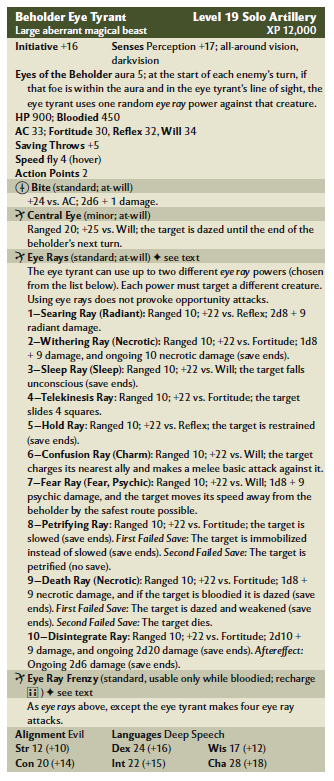

I think a stat block can tell you a lot about a roleplaying game. What types of information do you need to juggle? What does the game consider important in distinguishing one character from another? How complicated will the game be to prep and run?

Holding that thought in mind, let’s take a brief tour of the D&D stat block.

(If you’re not already familiar with the history of D&D, you might want to take a quick tour to orient yourself.)

THE 1970’s

The first published adventure module was “Temple of the Frog” by Dave Arneson in Supplement II: Blackmoor (1976). Everyone was still trying to figure out the entire concept of a “module” and how it should be presented, and “Temple of the Frog” didn’t actually contain stat blocks, instead describing everything narratively. For example:

Room 7: (Company Office) This contains two desks and chairs, a locked foot locker (and an old crypt in the walls of the room which contains five skeletons of 2 hit dice that have armor class 7 and move 6” per turn.

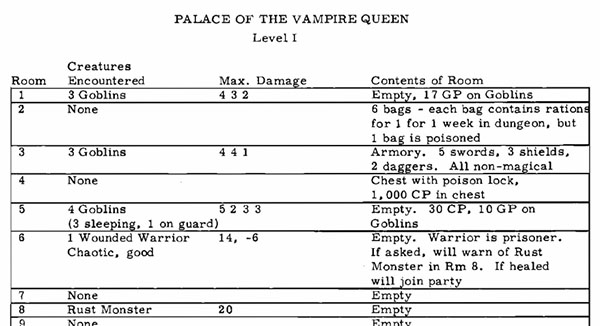

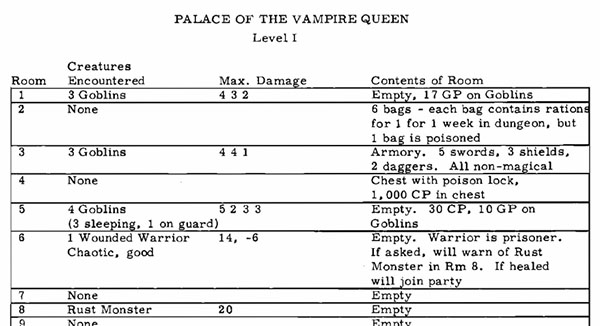

The next published adventure module was Palace of the Vampire Queen (1976) by Judy and Pete Kerestan, which was published by Wee Warriors. (As we’ll see, during this time period the state of the art was being pushed forward by a lot of third party publishers.) The entire adventure key for Palace of the Vampire Queen was presented in a semi-tabular fashion:

There’s not a really “stat block,” per se, but you could interpret one of sorts between the “Creatures” Encountered” and “Max. Damage” columns, e.g. “2 vampire guards — 23, 26.”

Later that same year the Metro Detroit Gamers published The Lost Caverns of Tsojconth, a convention scenario designed by Gary Gygax (based on an original adventure by Rob Kuntz) for WinterCon V. This mostly continues the “creature name + hit points” formatting, but formalizes it a little bit:

L.

10 SAHUAGIN: HP: 16, 14, 12, 11, 11, 10, 10, 9, 9, 7. These creatures appear at the eastern edge of the island within 1 turn of the voice (#7) speaking. They ATTACK. No treasure.

Notable here, however, is the first appearance of NPC spell lists:

K.

COPPER DRAGON: HP: 72. Neutral, intelligent, talking, has spells: DETECT MAGIC, READ MAGIC, CHARM PERSON, LOCATE OBJECT, INVISIBILITY, ESP, DISPEL MAGIC, HASTE, and WATER BREATHING. It is asleep and will waken in 3 melee rounds or if spoken to or attacked.

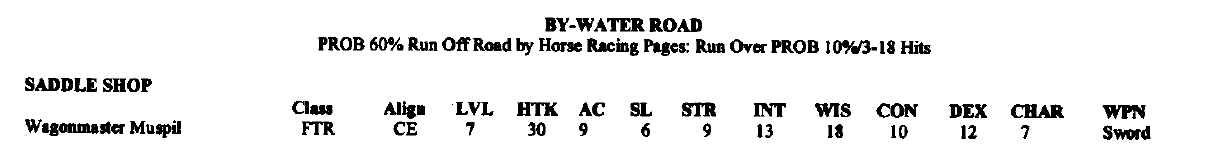

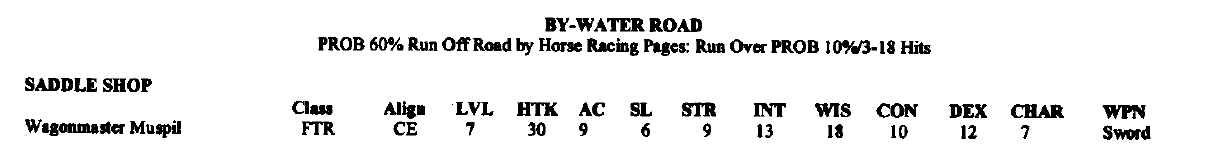

Still in 1976, we also have both the Gen Con IX Dungeon (by Bob Blake) and City-State of the Invincible Overlord (by Bow Bledsaw and Bill Owens) from Judges Guild. The latter used a tabular presentation for many NPC stat blocks:

These Judges Guild modules, however, also include what are likely the first true stat blocks with entries like this:

Two Mercenaries: FTR, N, LVL: 3, HTK: 1

Bartender Koris Brightips: FEM, FTR, CG, LVL: 2, HTK: 4, AC: 9, Dagger, sings.

Displacer Beast AC: 4 Move: 15” Hits: 22 Fights 5th Column

(“HTK” here is Hits To Kill. The original 1974 edition of Dungeons & Dragons notably used many different synonyms for what we now refer to as hit points. Thus HTK, Max. Damage, and similar entries can be found in many early stat blocks.)

We similar stat blocks from Judges Guild throughout ’77 in Tegel Manor, First Fantasy Campaign, and Modron.

In 1977, Wee Warriors also returned with The Dwarven Glory, another adventure by Pete & Judy Kerestan. The monsters here were still being described narratively, as they were in “Temple of the Frog,” but this adventure notably put the hit point totals and other stats in parentheses:

Room #6

2 ore carts, 10 lizard men (HP—5, 7, 10, 11, 10, 9, 8, 6, 7, 12) (AC—5) will try to ambush the party from ore carts. If unsuccessful, will fake panic and try to lead party into Room #5. Are on friendly terms with Cave Troll and Minotaur. Gem in dirt of floor with praying hands etched in surface (raise dead, usable once pe day).

I say “notably,” because in 1978 TSR figured out that there was a bunch of money to be made selling adventure modules and they came roaring into the market, releasing the G series, D series, S1 Tomb of Horrors, and B1 In Search of the Unknown. And this use of parentheses quickly became TSR’s house style.

G1 Steading of the Hill Giant Chief and the rest of the G series was written by Gygax as a way of taking a break between working on the Monster Manual and the original Player’s Handbook, and the parentheticals are still limited to hit points:

3. DORMITORY: Here 12 young giants (H.P.: 26, 24, 3 x 21, 18 x 17, 2 x 16, 14, 13) are rollicking, and beefy smacks, shouts, laughter, etc. are easily heard. All these creatures have weapons and will fight as ogres.

After finishing work on the Player’s Handbook, Gygax took another break and produced the D series. By this point, more information is being dropped into the parentheses (although the overall presentation remains fairly narrative):

Drow Male Contingent: There are 10 male fighters of 3rd level to the southwest, 2 of whom are on guard duty and will report the presence of any creatures moving along the passage. Other than having 13 hit points each and AC 0 (because of 16 dexterity each), they are the same as a male Drow patrol, i.e. +1 short swords and +1 daggers and carrying hand crossbows and using dancing lights, darkness, and faerie fire (at 3rd level) once per day per spell. There are 2 4th level fighters as leaders (H.P.: 18; AC -2) with +2 short sword, +2 dagger, and atlatl and 3 javelins. The commander of the unit is a 6th level fighter (H.P.: 28, +3 chain mail, +3 buckler, +3 for dexterity of 17, for an overall AC of -3) armed with +2 dagger, +4 short sword, and hand crossbow with 10 poisoned bolts.

By ’79, Judges Guild had firmed up their presentation of NPC statistics into definite stat blocks. For example, here’s the text from key V-5 in Dark Tower:

Avvakris: 10th level cleric of Set, Align: CE, chainmail, AC: 5, HP: 50, S: 14, I: 14, W: 15, D: 14, C: 11, CH: 15, weapon: mace, spells: bless (reverse), create water (reverse), detect good, detect magic, hold person (x3), silence 15′ radius, animate dead, dispel magic, speak with dead, cause serious wounds (x2), divination, flame strike (x2.)

Seth the Huge: 6th level fighter, align: CE, chainmail and shield, +3 dexterity bonus, AC: 1, HP: 34, weapon: longsword, S: 16, I: 8, W: 5, D: 17, C: 11, CH: 12. Large and cruel looking.

Wormgear Bonegnawer: 6th level fighter, align: CE, chainmail and shield, +1 dexterity bonus, AC: 3, HP: 48, weapon: longsword, S: 16, I: 11, W: 14, D: 15, CH: 11.

Over at TSR, Gygax was also firming things up. In T1 Village of Hommlet (1979), stats are still being dropped into the middle of paragraphs, but they’re being completely contained in parentheses (instead of leaking out as we saw with D1) and becoming increasingly standardized. Examples include:

Canon Terjon (6th level cleric — S 11, I 10, W 16, D 12, C 16, Ch 8 — chain mail, shield +1, mace; 41 hit points; invisibility and mammal control rings; typical spells noted hereafter)

Jaroo Ashstaff (7th level druid — S 11, I 11, W 18, D 9, C 15, Ch 15 — HP: 44, padded armor, cloak of protection +2, staff of the snake, +1 scimitar, ring of invisibility; spells given below)

black bear (AC 7; HD 3+3, HP: 25; 3 attacks for 1-3/1-3/1-6 plus hug for 2-8 on a paw hit of 18)

two dogs (AC 7; HD 1+1, HP: 5, 4, 1 attack for 1-4 hit points of damage)

THE LONG, SLOW EXPANSION

By 1980, therefore, stat blocks were assuming standardized forms and TSR was beginning to create editorial standards which applied to all of their books. (This is a trend you can also see with TSR’s dungeon keys.)

When T1 was republished in 1985 as part of T1-4 Temple of Elemental Evil, the stat blocks were revamped for this standard:

Black Bear: AC 7; HD 3 +3; hp 25; #AT 3; D 1-3/1-3/1-6; SA Hug (if paw hit 18+); Dmg 2-8; XP 185

Jaroo Ashstaff: AC 6 (padded armor); Level 7 Druid; hp 44; #AT 1; D by weapon or spell; XP 1427; cloak of protection +2, ring of invisibility, staff of the serpent (python), scimitar +1

S11 I 11 W 18 D 9 Co 15 Ch 15

Standard druid abilities: identify plant type, animal type, pure water; pass without trace; immune to woodland charm; shapechange 3 times per day; +2 bonus to saving throws vs. lightning; q.v. PH page 21.

Spells normally memorized:

First level: detect magic, entangle, faerie fire, invisibility to animals, pass without trace, speak with animals

Second level: barkskin, charm person or mammal, cure light wounds, heat metal, trip, warp wood

Third level: cure disease, neutralize poison, summon insects, tree

Fourth level: cure serious wound, plant door

Spell lists are obviously, by their very nature, lengthy. But you can see how compact and, arguably, even elegant the standardized “stat-line” format is for the stat block. Albeit nearly incomprehensible when you first look at it, it doesn’t take much familiarity with the rules before this stat block becomes very easy to use by virtue of taking every piece of necessary information and putting it right at your fingertips.

BECMI stat blocks were largely identical:

Goblins. (2d4) AC 6; HD 1-1; hp 3 each; MV 90′ (30′); #AT 1; D 1d6; Save NM; ML 7; AL C; XP 5 each. Each goblin carries a spear and 2-12 ep.

Champion (7th level Fighter): AC 6; F7; hp 42; MV 120′ (40′); #AT 1; D 1d4 (+2 for magic weapon); Save F7; ML 9; AL L; XP 450.

And the formatting of these stat blocks was largely unaltered when 2nd Edition rolled around. Here’s a sample from a late-2nd Edition module:

Behir: AC 4; MV 15; HD 12; hp 70; THAC0 9; #AT 2 or 7; Dmg 2d4/1d4+1 (bite and constriction) or 2d4/1d6 (bite/6 claws); SA once every 10 rounds can breathe bolt of lightning up to 20 feet long that inflicts 24 points of damage (save for half), swallow whole on an attack roll of 20 (victim loses % of starting hp until death on the 6th round, can cut himself out by attacking AC 7, but each round the victim spends inside the behir he faces a cumulative -1 damage penalty); SD immune to electricity and poison; SZ G (40′ long), ML Champion (15); Int Low (7); AL NE; XP 7,000

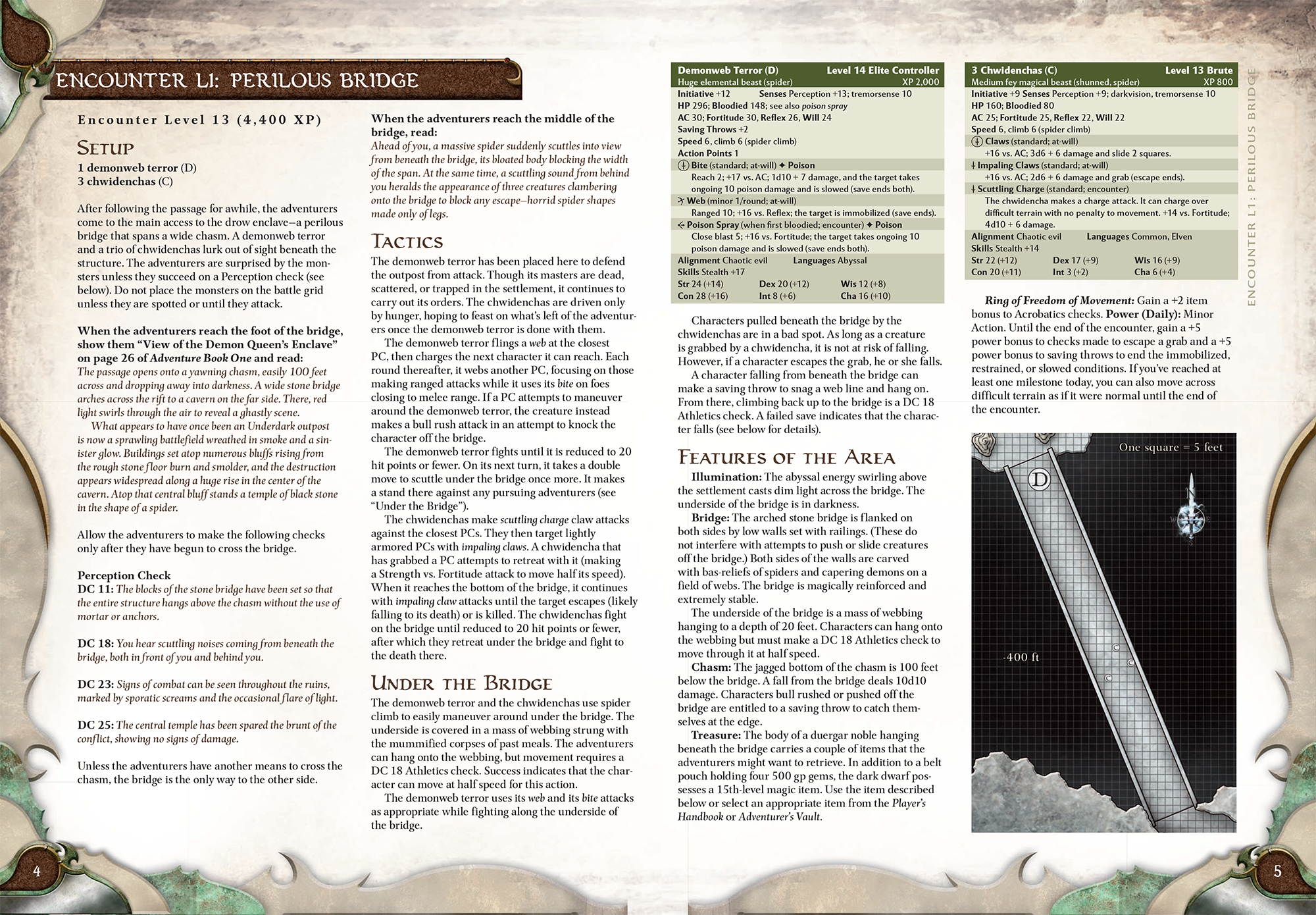

Here, though, we can start making two additional observations. First, as the rules for a creature become more complicated, the short simplicity of the stat block begins to decay into a mass of incomprehensible text.

Second, the earliest stat blocks were kept minimalist in part because many stats were standardized by Hit Dice and keyed to a unified chart. As the rules for creatures became less standardized, more information needed to be coded into the stat block (like THAC0), directly contributing to the “mass of text” feel.

Go to Part 2: The 21st Century