Character Backgrounds by Chris Malone

I originally designed Left Hand of Mythos as a convention scenario for Gen Con 2017. It rapidly metastasized beyond that purpose and had to be rapidly abridged to fit within the four-hour convention slot.

My compatriot, collaborator, and co-GM at Gen Con that year was Chris Malone. To facilitate convention play, Chris designed four fabulous pregenerated Trail of Cthulhu characters. Following the best practices we had learned during the Cthulhu Masters Tournament, these included fully developed backgrounds for each character, including tightly knit relationships with each other to empower the players to seek strong, powerful roleplaying choices.

We ended up using these same characters for several other sessions at our local tables, including an adaptation of the classic “Edge of Darkness” scenario for Call of Cthulhu, which was restructured to feature the death of Father Rand.

DOWNLOAD THE CHARACTER SHEETS

(PDF)

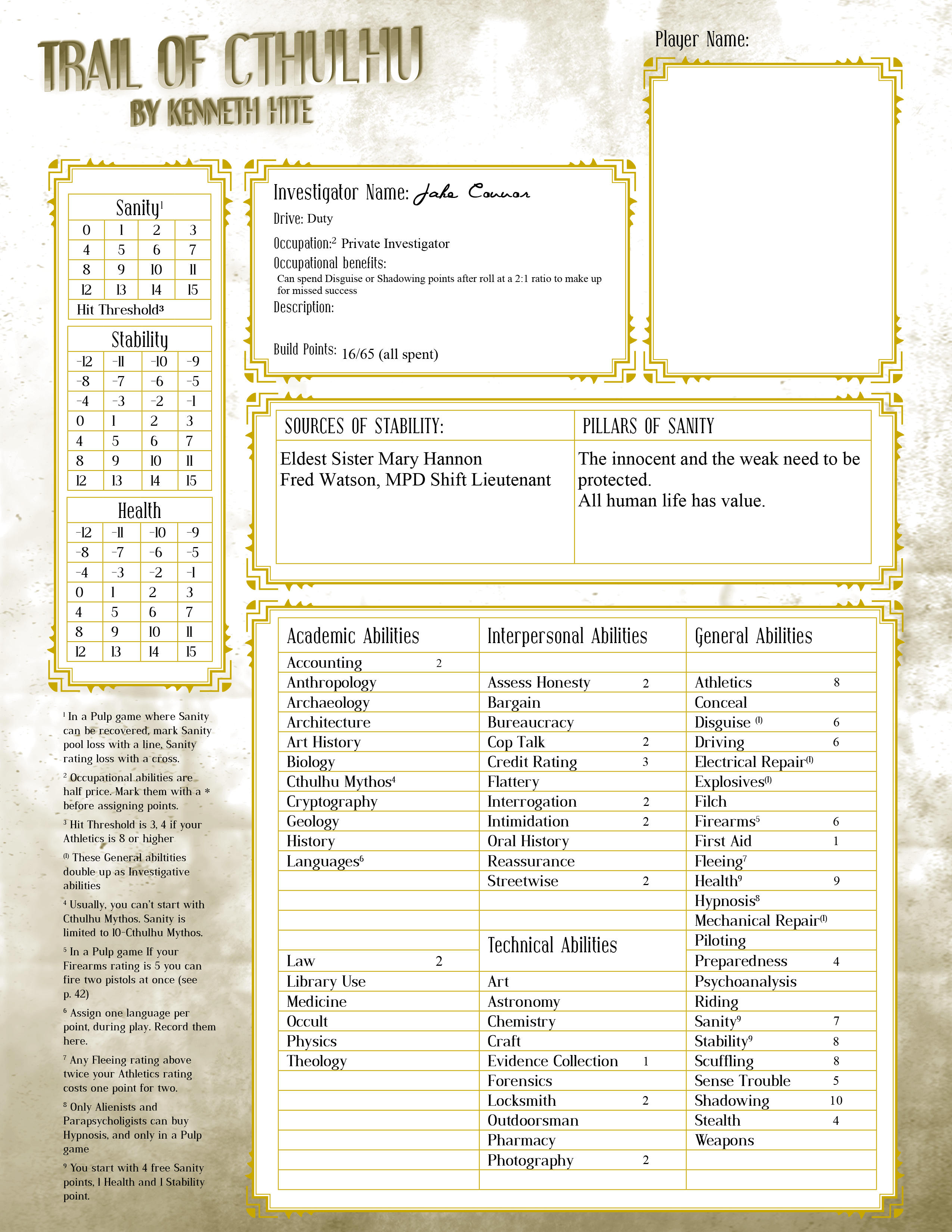

JAKE CONNOR, PRIVATE INVESTIGATOR

Age: 29

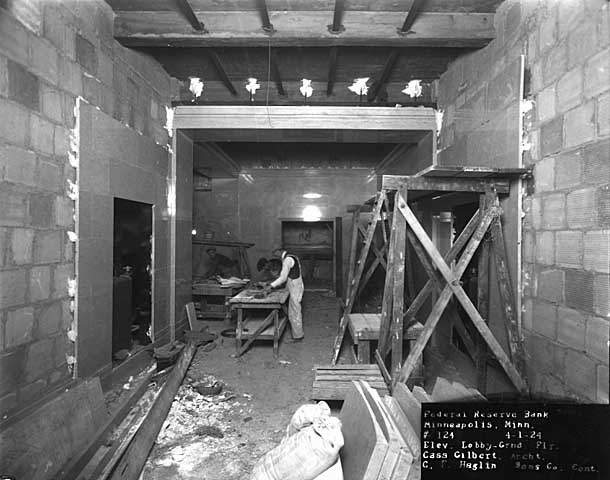

Jake was born in Minneapolis to a Protestant family of Irish and English immigrants. The eldest son (his sister Mary is the eldest of the family), expectations were set high for Jake and he constantly struggled to meet the expectations of his parents. While life was never easy for Jake as he was growing up, he never experienced true poverty. Jake left school early to work a pair of jobs to support the family, and found himself struggling with the monotony of toil without the promise of something greater. At the onset of The Great War Jake joined the Army in hopes of making a difference. His parents were furious, and all but disowned him as he headed off to basic training.

Initially trained as an infantryman, Jake showed a flair for writing and photography and was detailed to the press corps where he served primarily as a cameraman, documenting the events of the war. He was frequently detailed to create propaganda images and write messages to encourage the purchase of war bonds, as well as improve enlistment. During one such assignments he was matched with Maxwell Bruener, the son of a wealthy young German industrialist who had “enlisted” to help improve recruitment among German-Americans. A quick friendship was formed, and although they only spent several months together.

Through the detachment of the camera, Jake could distance himself from the horrors of the war and returned home afterwards plagued only by infrequent nightmares and a mild case of claustrophobia. Upon his return to Minneapolis he worked for a short stint at the Minneapolis Tribune as a beat writer and photographer. With the onset of prohibition, Jake wrote several scathingly critical anti-Prohbition articles which ultimately cost him his job, but endeared him to certain elements of the Twin Cities underworld. With these connections beginning to form, Jake found himself able to find work investigating minor offenses in the criminal underworld and solving crimes that people would rather not bring to the police. He now runs a private detective business, making use of his excellent photographic skills to further his business.

Jake’s reputation has taken an odd turn after he solved a missing persons case several years ago. Two seemingly separate instances of a young man and a young woman disappearing led Jake and his companions to a secretive cult operating within the Freemasons that was engaging in human sacrifice in the name of some esoteric and foul deity. Jake and company acted quickly and rescue one of those who had disappeared (the other, sadly, was long dead) and bring the perpetrators to justice. Now the local police come to Jake occasionally with queries or leads into strange or occult cases.

RELATIONSHIPS

Maxwell Bruener — Max and Jake have remained close friends after the war, and frequently spend time together. Jake doesn’t always understand Max’s philosophical ramblings, and often argues with him over Prohibition (Max is a staunch advocate for the Volstead Act and Prohbition), Jake does appreciate Max’s enthusiasm and kindness. Max proved himself to Jake during the Freemason investigation, as when the chips were down in the hidden sanctum, Max threw himself into the fray, fighting to stop the murder of an innocent.

Father Gustav Rand — Max introduced Jake to Father Rand some months prior to the Freemason as a good friend. Unlike the clergy Jake had grown up with and met during the war, Rand showed himself to be a friendly, easy-going sort with a great deal of intelligence and wisdom. During the Freemason case, Rand provided valuable insight into several clues linking evidence from the victim’s residences to the inner cult at the Masons. Jake has grown to respect Rand’s input and value his council, even if he is a Papist.

Margaret Pearson — Maggie is Jake’s cousin, come over from Boston to get her doctorate in the Sciences from the University of Minnesota. Looking to reconnect with his family and get back into their good graces, Jake has taken it upon himself to protect Maggie and ensure that she is not abused. Against better judgement, Jake asked Maggie to help with examining some of the evidence during the Freemason case. She was able to identify a unique sedative used during the abductions, and link it to a crucial suspect with access to it. You find her forensic skills and apt mind invaluable in difficult cases.

MAXWELL BRUENER, DILETTANTE

Age: 35

The son of a rich German manufacturing magnate, Maxwell Bruener grew up in Minneapolis in relative ease and luxury. His father, Jurig, was an overbearing and demanding man. He detested Maxwell’s adventurous spirit and gentle heart, and was a strict disciplinarian, often resorting to physical punishment, especially when he was drunk. Maxwell thrived despite his father’s frequent beatings and denouncements, and spent most of his youth and early adulthood exploring literature, the arts, and sports.

When America formally joined the War Jurig forced Maxwell son to enlist, hoping to either toughen him up and turn his mind to more serious matters or kill him off. This idea was not kept a secret to Maxwell, as the last letter from his father during training read “come back a man in my own mold, or as a corpse to be buried”. Despite his father’s insistence to Max’s commanders of fair treatment, Max was seen by elements in his command as a recruitment opportunity. He had a member of the press corps, Jake Connor, assigned to him to document his time in the Army to drive recruitment of the somewhat reticent German-American population, as well as facilitate war bonds. Jake and Max became fast friends, and spent many evenings sharing stories and ideas in good company.

Max avoided significant action in the War until he took part in the Third Battle of the Aisne in defense against the German Spring Offensive. Ten days of shelling, gas attacks, mud, and death almost broke Max’s spirit. Without Jake’s reassurance and strength, Max is certain he would have either died or come out of the war a much different man. Max survived the Battle physically untouched, but was scarred by the experience.

In an ironic twist of fate, Max was called back home mid-May following the battle due to the death of his father, whose days of drinking had finally caught up to him. With the affairs of the estate quickly put into order and business well-managed with little demand from Max, he found himself melancholic and desperate. Max began filling his time with philanthropy and personal growth. Home in time for the political machinations around the Volstead act, Max strong supported the temperance movement and the outlaw of liquor, pledging money, support and influence to the cause. In addition to his altruistic and political engagements, Max began to participate in theosophical societies and delved into philosophical texts, even dabbling into the occult. These explorations brought him into contact with Father Gustav Rand, a catholic priest who talked of religion in a way that encouraged Max’s exploration, without condemnation or proselytization.

At times Max helps Jake out with his private investigation work as a diversion into more exciting occupation. Several years ago, you, Jake, Father Rand, and Jake’s cousin Maggie helped him clear a case that was most unusual. Two seemingly separate instances of a young man and a young woman disappearing led Jake and his companions to a secretive cult operating within the Freemasons that was engaging in human sacrifice in the name of some esoteric and foul deity. Jake and company acted quickly and rescue one of those who had disappeared (the other, sadly, was long dead) and bring the perpetrators to justice. During the fray, Max found strength and purpose, charging into the fray and fighting the cultists with vigor. Now the local police come to Jake occasionally with queries or leads into strange or occult cases.

RELATIONSHIPS

Jake Connor — Jake is Max’s closest friend and confidant. While Jake is disinterested in Max’s spiritual and philosophical musings, and they disagree vehemently on the matter of Prohibition, Max cannot imagine a better ally. Max rarely feels more useful or competent than when he is working a case with Jake.

Father Gustav Rand — Father Rand is Max’s intellectual and spiritual mentor, allowing Max to explore the world of the unseen without prescribing his Catholic dogma or suggesting a right way of things, merely saying “I know you’ll come around to the right way of it sooner or later, they all do…”.

Margaret “Maggie” Pearson — Maggie, Jake’s cousin, is like no other woman that Max has met. Her high-spirited nature, quick wit, and vast knowledge have intimidated Max at times, and she seems to enjoy stumping Max. Regardless, Max is thoroughly taken with her, and has been spending time perfecting a poem that he plans to deliver to her to begin courting her.