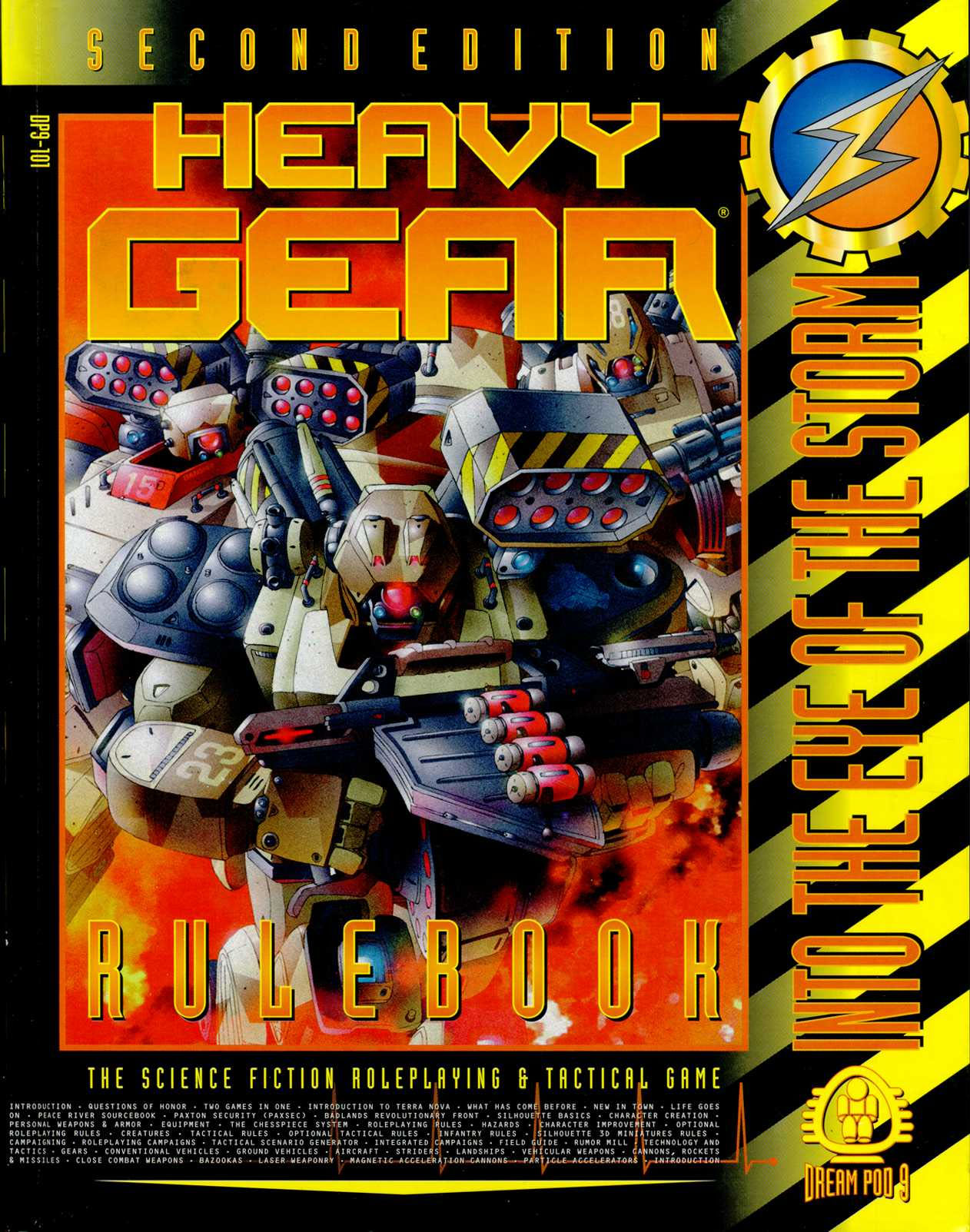

Tagline: Heavy Gear is, in the words of the publisher, “not your father’s giant robot game”. One of the best games of the ’90s, the second edition of this game is everything a second edition should be and more.

This review gushes a bit, but more than a decade later Heavy Gear is still one of my favorite games and Terra Nova is one of my favorite settings. I will also say that the Heavy Gear game line during its first and second editions remains an almost perfect example of how RPG product lines should be organized.

There are a lot of games out there and there are a lot of settings out there and, usually, even if I like a game or setting in general there are products for that game or setting with which I am not happy. We can all think of an example where the publisher’s of our favorite game have let us down by releasing an inferior product.

There are a lot of games out there and there are a lot of settings out there and, usually, even if I like a game or setting in general there are products for that game or setting with which I am not happy. We can all think of an example where the publisher’s of our favorite game have let us down by releasing an inferior product.

It has been a pleasant surprise, therefore, for me to encounter the games of Dream Pod 9 – although I have yet to purchase every supplement for their games, I have bought the majority of them and can testify that not a single one of them has been a disappointment. Whereas other game companies have to prove to me that their product is worth my money, Dream Pod 9 would have to prove to me that their product is not worth my money before I would consider not buying it. I may not own all the supplements yet, but I intend to the minute it is within my financial ability.

It therefore came as no surprise to me that the second edition of their Heavy Gear game proved to be a textbook case of not only how to do a core rulebook, but how to do a second edition.

The first edition of the Heavy Gear game (“A New Era Has Just Begun”) was released three years ago in 1995. I didn’t pick it up until just last year (literally the day before the second edition was announced on Dream Pod 9’s website). With fully integrated rules for both roleplaying and tactical play it had a powerful system with a lot of potential in a visually stunning package. It was possessed with some minor flaws, of course (no game is perfect): the material was very tightly packed with some degree of muddiness in the lay-out and the chapter on the world of Terra Nova (where Heavy Gear is set) was only six pages long.

Over the next two years Dream Pod 9’s general competency at laying out material would increase and it would be revealed (through supplements such as Life on Terra Nova) that the universe of Heavy Gear and the story being told there are even better than the rules.

This is where the second edition comes in. The folks down at Dream Pod 9 managed to perfectly target every problem area of the first edition, leave every feature of the first edition intact, and release a second edition which every other game publisher in this industry should take as a model. The first edition of Heavy Gear was fantastic. The second is sublime.

First, they have taken advantage of two years of experience and player feedback. Specific problem areas in the rules have been resolved and cleaned up. The overall lay-out and structure of the book has been redone in a manner which is both clean and logical – making the game easier to learn for newcomers and easier to reference for active players.

Second, they have added an extensive chapter on the background of the game – with general information on the entire world of Terra Nova along with an in-depth look at the city of Peace River in order to provide a beginning location for new GMs. This section also contains a beautiful full-color map of Terra Nova. The first edition of the game presented an odd dichotomy – everyone said the outstanding setting and developing story of Terra Nova was the biggest strength of the game, yet the rulebook contained almost no information on that setting or story. The second edition has resolved this problem.

Third, they have left intact everything which was good in the first edition. The rules are still simple, yet powerful. They still provide perfect integration between roleplaying and tactical games for those who are interested. The visual presentation is still stunning.

Too often when publishers release second editions of great games they have spoiled what was there to begin with – cluttering the elegant design of the first edition with unnecessary rules and complexity, destroying the essence of the original game, and catering towards people who are already playing the original edition. The second edition of Heavy Gear has done none of this.

THE RULES

In my discussion of the rules I am only going to deal with the roleplaying components of them – as I am not an experienced tactical player with this system. The tactical system is 100% compatible with the roleplaying system (with only a simple scale change involved), however, and is (by all reports) of excellent quality in its own right.

The central mechanic of Heavy Gear is simple. To perform any task you perform an Action Test. Roll a number of six-sided dice – whichever die is the highest is your total. If more than one six is rolled, each additional six is treated as a +1 (so rolling three sixes would result in a total of 8 (6+1+1)). If you roll all 1’s you have fumbled. Certain modifiers may add to or subtract from your total.

In a Standard Action Test, unless you fumble, you compare your total to a Threshold assigned by your GM to the action in question. If your total is higher than the Threshold, you have succeeded. If it is lower, you have failed. Your Margin of Success is the total of your die roll minus the Threshold. Your Margin of Failure is the Threshold minus your die roll.

In an Opposed Action Test you simply compare the two rolls – whichever is higher succeeds. A draw is a marginal success for the person resisting an action. The Margin of Success is determined by subtracting the lower total from the higher total.

This basic mechanic will be used most often to perform a Skill Check (there are also Attribute Checks and Chance Tests). In a Skill Check the number of dice you roll is equal to your rating in the skill you are attempting to us. Whatever attribute is effecting the roll acts as a positive modifier to the roll.

An example: Miranda Petite is attempting to do a backflip. She has a skill level of 2 in Acrobatics and her rating in the Agility attribute is 3. Because she has a skill level of 2 she rolls two dice. She rolls a 5 and a 4, so her total die roll is 5. She adds 3 to this (from her Agility attribute) for a final total of 8. If the GM had assigned a Threshold of 3 (Easy) to this task, Miranda would succeed with a Margin of Success of 5 (8 – 3).

Combat is handled as a series of opposed action tests, with various modifiers applied according to factors (cover behind which your target is hiding, lighting, the amount of time you spend aiming, the accuracy of your weapon, etc.). Damage is calculated from the Margin of Success of the attack by multiplying the MoS and the damage rating of the weapon. A character has three Wound Thresholds – Flesh Wound, Deep Wound, and Instant Death. The damage is compared to the Wound Threshold of the character – if it exceeds the character’s thresholds, the character takes a wound.

Character creation is a process of purchasing attributes and skills, as well as calculating secondary traits. The points for attributes and skills are separated – but there is provision for converting unused characters points (used for purchasing attributes) into skill points. There are ten attributes (Agility, Appearance, Build, Creativity, Fitness, Influence, Knowledge, Perception, Psyche, and Willpower) and nine secondary traits (Strength, Health, Stamina, Unarmed Damage, Armed Damage, Flesh Wounding Score, Deep Wounding Score, Instant Death Score, and System Shock).

THE SETTING

Heavy Gear is set 4000 years in the future. During that time we have perfected a system of interstellar travel using “Tannhauser gates” (named after the scientist who’s Grand Unified Theory explained time-space discontinuities – the “gates”) and begun to settle the galaxy – including the Helios system where the planet of Terra Nova is located.

Terra Nova is a largely dry planet. Slightly larger than Earth it’s equatorial region is a vast desert referred to collectively as the Badlands. Its polar regions, however are fertile and were centers of the colonization effort.

At the end of the 58th century, however, Earth decided that the benefits of the colony worlds was no longer worth the financial burden of supporting them and withdrew their support – including the massive gateships required for interstellar travel. Terra Nova suddenly found itself isolated from the rest of humanity.

Years of chaos ensued. Slowly, however, means of staying alive on this strange and hostile world without the aid of the home world were found. Political leagues were formed – in the southern hemisphere the Southern Republic, the Humanist Alliance, the Mekong Dominion, and the Eastern Sun Emirates; in the northern hemisphere the Northern Lights Confederacy, the United Mercantile Federation, and the Western Frontier Protectorate. The polar leagues eventually formed two polar alliances – the Allied Southern Territories and the Confederated Northern City-States. The Badlands, however, remained largely a hostile and volatile geopolitical area with various city-states and smaller communities.

Then Earth returned – in the form of the Colonial Expeditionary Forces (CEF). What ensued was the War of the Alliance – as the two polar confederations, typically political enemies, allied with each other against the common foe. Finally the CEF forced to retreat back through the gates and the spirit of cooperation did not last long after their leaving. Now, nearly two decades later, the two polar alliances are on the verge of war.

The rules of Heavy Gear are simple and elegant, but the setting is a work of art. The cultures of the various leagues are rich tapestries – each with their own character and individuality. The political spectrum of this world is complicated and detailed. As you delve into the supplements you get details not only on broad patterns, but also on how people actually live their lives. You will not find a better game world on the market today, in my opinion. Period.

HEAVY GEAR: THE GAME LINE

At the beginning of this review I mentioned the supplementary products for the Heavy Gear game. There are not many games so well supported as Heavy Gear. In an industry which suffers alternatively from vaporware deadlines and large gaps of time between releases, Dream Pod 9 has committed themselves to both an adherence to deadlines and near monthly release schedule for the Heavy Gear game since its inception. And the products released do not suffer from the speed at which they are produced. Quite the opposite, the quality of Heavy Gear products is consistently among the best in the industry (they were nominated for two Origin awards this year, for example).

My favorite aspect of the entire game, however, are the Storyline books – coupled with the Timewatch(TM) system. Although only one (Crisis of Faith) has been released so far, the concept is fantastic and should, I think, be emulated by other games. The universe of Heavy Gear, like many others, has an advancing timeline – let’s call it a meta-story which is told behind which the primary stories (those told by the GMs and players). The problem many other games have is that following that meta-story becomes increasingly difficult as more and more products are released. Take Shadowrun, for example. There are dozens upon dozens of products available for Shadowrun, and through those products a story is told – but new players have very few clues available to them as to where to start. The other problem is that – because that story is told over the course of all those different products – to follow it requires an ever-increasing financial investment. I, as a new player to Shadowrun, found that investment quite daunting and – instead – chose to create the material myself.

The Storyline books and Timewatch(TM) system which are part of the Heavy Gear line, however, solve both these problems. First, the Timewatch(TM) appears on the back of all Heavy Gear products – giving the game year in which the product is set. For example, the Second Edition Rulebook is set in TN 1934. This makes it very easy for new players to know exactly when a product is set. Second, the Storyline books are designed to push the meta-story of the world forward. Although they capitalize on hints and material found in the other sourcebooks, they are stand-alone products and tell the most important parts of the evolving story of Heavy Gear.

What this means is that, first, any supplements that players buy for the game can be quickly identified as to the time period they are discussing. Second, for players who don’t want to obsessively buy every product which comes out for the game, they can still follow the evolving meta-story. This means that if I wanted to run a campaign in the Humanist Alliance I wouldn’t have to buy supplements for the completely unrelated area of the Northern Lights Confederacy because the NLC sourcebook contains elements of the evolving meta-story I will require to understand future products released concerning the area I am really interested in, the Humanist Alliance.

CONCLUSION

Heavy Gear is blessed with a great system (which supports both roleplaying and tactical playing), a fantastic setting, and an excellent line of support (in quality, in timeliness, in detail, and in organization).

Dream Pod 9’s recent advertising for this game has included the tag line: “This is definitely not your father’s giant robot game.” I think it’s important to note that this 100% true. Many giant robot games tend to focus more on the technology than on the characters, but the world of Terra Nova is so deeply and richly textured that it is more than possible to adventure there without ever seeing or getting into one of the “gears” from which the game gets its name (you’ll note that they have not once come up previously in my review). They are part of the world, but they are not the entirety of the world by any stretch of the imagination.

The world is so wonderfully detailed, in fact, that I have seen games run within their fictional cultures which could just as easily have been run in a modern setting with a few minor technological changes. This game can be satisfying to those interested in any genre of play, because the world is large enough and realistic enough to realize that interesting stories can be told about anybody and anything.

I said earlier that no game is without a flaw. The second edition of Heavy Gear is no exception, although I had to look for quite some time to find it: A lot of the artwork is recycled. This would not be a bad thing if it was merely recycled from the first edition rulebook – however, many of the pieces are, in fact, from other sourcebooks. For those of us who are Heavy Gear junkies and used to every book getting a fresh and excellent art treatment, seeing these pictures a second time was an unwelcome surprise. New players entering the game will undoubtedly get the unfortunate impression that Dream Pod 9 is in the business of recycling art for their supplements.

As flaws go, this one is so insignificant as to be meaningless. This is a game you should buy. Right now. In fact, get up from your computers, go to your car, drive to you game store, buy it. Right now. Go.

What are you still doing here?

Style: 5

Substance: 5

Author: Philippe R. Boulle, Jean Carrieres, Elie Charest, Gene Marcil, Guy-Francis Vella, Marc A. Vezina, and other contributors.

Company/Publisher: Dream Pod 9

Cost: $29.95

Page count: 240

ISBN: 1-896776-32-9

Originally Posted: 1998/05/08