SESSION 42A: RAT MOTHERS

October 17th, 2009

The 23rd Day of Kadal in the 790th Year of the Seyrunian Dynasty

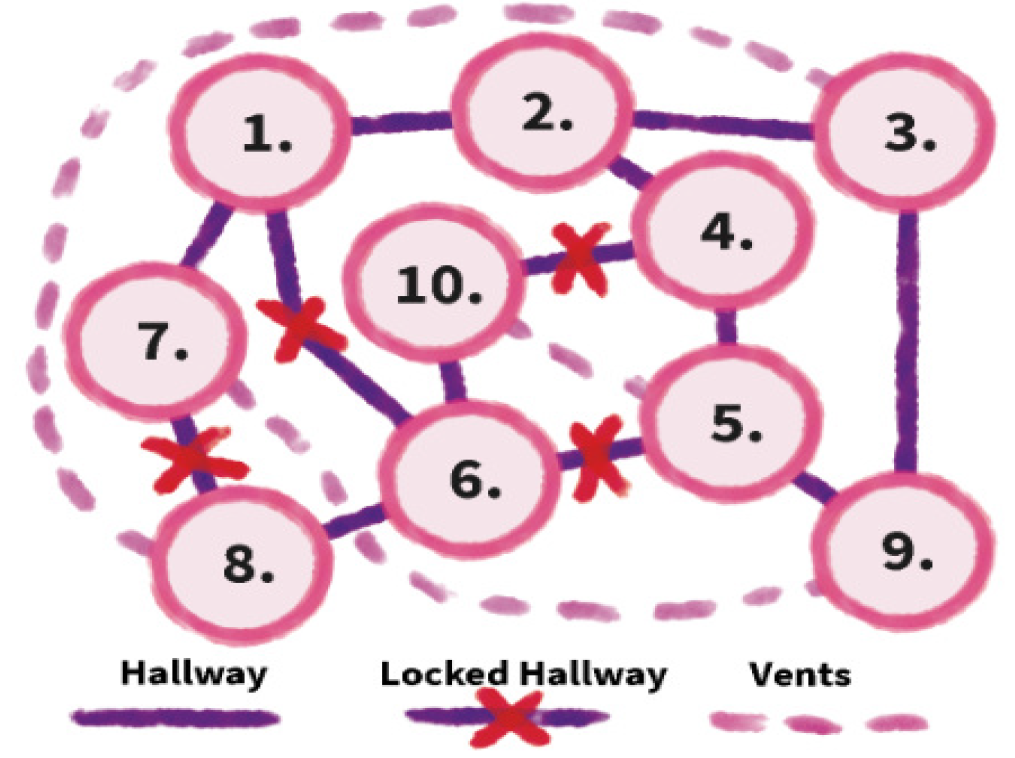

They burned their way through Ranthir’s web and passed into another trash-filled chamber. Rising out of the trash on the far side of the chamber, however, was a ten-foot-tall stone statue of a ratling. Its head was lowered, staring into the dark depths of a wide sinkhole that lay at its feet.

They were wary of the statue – thinking perhaps that it was cursed, enchanted, or trapped in some way – but ultimately chose to investigate it. In a hidden compartment at the rear base of the statue, Tee found three scroll cases: One contained a stack of gold and silver coins; another a copy of the Truth of the Hidden God; and the third an arcane scroll.

Uncertain of what might emerge from the sinkhole if they left it at their backs, Tor quickly tied a rope around Tee’s waist and lowered her into the darkness. The sinkhole bottomed out into a large, conical cavern. Near the limit of the light she carried, Tee could see a couple passages twisting away from the cavern. On the large wall nearest her she could see cave paintings: Rat-shaped humanoids worshipped a huge, bulbous rat. Gouts of flame seemed to erupt from the rat’s sides, and in the midst of the flames Tee could see white rats dancing in the infernos.

Something about the painting disturbed her deeply, and after studying it for a few long moments she tugged twice on the rope – giving the signal to draw her back up.

After Tee had described what she had seen, they discussed their options. Ranthir, as was his wont, strongly opposed delving deeper before finishing the exploration of the current level of the nests. Besides, they suspected that they were on a level with the Midtown sewers – delving deeper into the caverns beneath the city wouldn’t get them where they wanted to go.

THE MOTHERS

Leaving the chamber with the statue, they passed through the far end of a long hall filled high with even more of the rats’ garbage. Tee passed silently over the surface, but, of course, Agnarr and Tor made an unearthly racket wading their way through. In the process, they attracted the attention of several large rodents which emerged out of the trash heaps: They had pale, chalk-like fur and eyes which glowed like fierce embers of flame.

“Who’s there?”

The voice came from the direction they had been heading. A huge, lumbering ratbrute emerged from the shadows.

Tee turned to face him. “We’re looking for the sewers.”

“Who are you?”

“Silion sent us to the southern sewers. We have business with Porphyry House.”

A befuddled look passed over the ratbrute’s features (which was surprising, considering how befuddled they already looked). “I guess if Silion sent you…”

“That’s right,” Tee nodded encouragingly. “Now, where can we find the sewer?”

“There’s an entrance beyond the mothers.”

“Where are the mothers?”

“Right over here.” The ratbrute turned and started lumbering back the way it had come.

Tee looked back at the others as if to say “I can’t believe that worked” and then, with a shrug, followed the ratbrute.

The passage he took them down was relatively broad and surprisingly free from debris. They passed another of the tattered blue curtains, and Tee took a moment to poke her head through it: The chamber beyond was unnaturally chill and contained a variety of bloated corpses – dogs, birds, cats… and a few humans. The bodies had been variously dismembered, with a few pieces here and there having obvious gnaw-marks on them. (Ranthir identified the chill as coming from a simple cantrip, most likely cast here to permanently keep the room cool enough to preserve the “meat”.)

“Are you coming?” The ratbrute looked at them curiously.

“Of course,” Tee said. Hurrying after him, she drew her sword and pointed it at the ratbrute’s clueless back.

Pushing through another blue curtain, they emerged into a large chamber containing several of the now familiar ratling nests… along with half a dozen female ratlings. The mothers. Everyone froze: Ratlings staring at humans; humans staring at ratlings.

“Tattum! What have you done?!”

The mothers scattered. Tee stabbed Tattum in the back.

Tattum, roaring in pain, drew his greatsword in a massive sweep that caught Tee with the flat of the blade and sent her staggering.

Nasira, meanwhile, noticed that several of the chalk-white rats from the hall of refuse had been following them. She was about to call out a warning when the melee broke out.

And then the chalk-white rats burst into balls of bright flame.

As Tee fell back towards Nasira, one of the flaming rats – pouring inky black smoke into the air – spit a ball of fire at Nasira, catching her full in the chest. Agnarr and Tor, meanwhile, were moving up to form a line against the enraged Tattum.

Several of the mothers had dashed out of the room through other exits, while others circled around the melee shaping up at the cave mouth – dashing in and delivering blows whenever they found an opening.

Tor managed to inflict a few deep wounds on Tattum’s massive frame, but then one of the mothers managed to latch onto his arm. Another, going low, sunk her teeth into his leg. Tattum, seizing the momentary advantage, found a chink in Tor’s armor and, ripping the blade free, caught Agnarr with a devastating back-swing.

Elestra dove forward, pouring the strength of the Spirit of the City into Agnarr’s wounds. Tattum, thinking Agnarr dispatched, stepped over him to take another swing at the badly injured Tor—

And Agnarr plunged his blade up through the ratbrute’s crotch.

(Which was becoming something of a habit.)

Tattum stumbled backwards as another ratbrute pushed through the curtain on the far side of the room. “Tattum! What the hell is going on?! If you’re in another—Oh shit! Fudd! Get out here!”

Fudd, a third ratbrute, pushed his way through the curtain. “What has he done now, Berq? … Oh shit!”

As Tattum fell for the last time, Fudd and Berq rushed Agnarr and Tor. Agnarr, however, was in the full heat and flow of the battle. He stepped forward and in a series of smooth blows that looked like perfect arcs of flame dropped Fudd in his tracks. Berq was more cautious, however, and moved into a careful dance of blades with the two fighters.

The blue curtain swept aside once more, revealing an aging albino ratling. He lowered a dragon pistol and fired, but Tor narrowly dodged the blast (which passed harmlessly over Tee, who was finishing off the last of the ash rats with Ranthir and Nasira).

As the separate melees raged, punctuated with blasts from the albino ratling’s dragon pistol, the mothers who had fled into a side-chamber returned – each bearing ratling babes in her arms. The albino ratling cried out to them, “Flee! Run as fast as you can!”

But Ranthir, upon hearing the word “flee”, whirled around and webbed the far side of the room: The mothers, the albino, and Berq were all helplessly caught – except for one mother, trapped in the corner, who futilely screamed for help in her despair. Tor closed on her and ruthlessly killed both her and the baby ratlings.

Agnarr, meanwhile, was finishing off Berq. This gave the albino ratling enough time to rip his own way free from the web. Cutting another mother free, he took her and ran for it.

Tor and Tee chased him down, but before he was killed, the albino managed to buy enough time for the mother to escape into the effervescent chamber of the true temple. Tor and Tee skidded to a halt and cautiously retreated back the way they had come.

Several of the mothers were still trapped in the web. Tee was able to broker a bargain in which they would be freed if one of them would lead the party to the southern sewer entrance. While the mothers were carefully freed from the web, Tor started discreetly taking ears and fingers from the dead as trophies. Meanwhile, Elestra distracted the ratlings with small talk to keep them from noticing Tee looting the coffers of the nest master (which were filled with gems, jewelry, and large amounts of coin; although given the bones and skulls dangling from the ceiling, Tee didn’t want to spend too much time thinking about where it had all come from).

Running the Campaign: Killing Orc Babies – Campaign Journal: Session 42B

In the Shadow of the Spire: Index