I’ve mentioned before that my Thracian Hexcrawl consists of a 16 x 16 map in which every hex has been keyed with geography: That’s 256 hex keys.

Several people have asked me how I did that. Here’s the first secret: When you’re prepping material for yourself, polish is overrated. (Details are also overrated, with the proviso that essential details and awesome details should always be jotted down.)

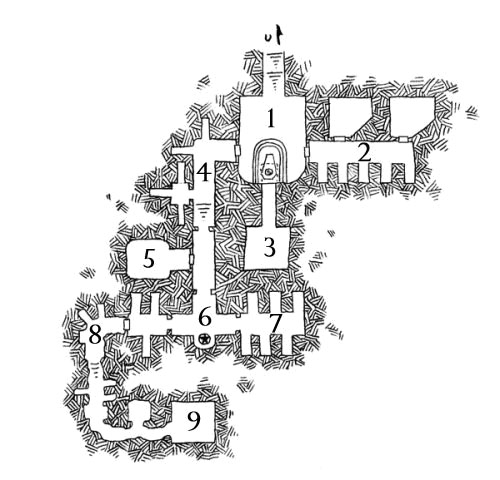

For example, consider the Skull Rock mini-dungeon I posted in Part 8. If I were writing this dungeon up for someone else to use, I’d probably take the time to mention how wet and slick the stairs leading down into area 1 are (due to the river above); the damp moistness in the air of the first chamber (providing a slight haze that can be burnt away dramatically by the flames of the dragon head); and the way that dampness gives way to a chilled condensation that hangs in glistening drops from the rough hewn walls as you descend into the dungeon.

But since I’m just prepping this for myself, I don’t need to write that down.

Trust your own voice as a GM. During play, based on your intrinsic understanding of the scenario and the environment, it will provide the logical and evocative details necessary to flesh things out.

And by placing that trust in yourself, you can save yourself a ton of prep time. (Something like Skull Rock would take me seven or eight times longer to write-up if I took the time to include and polish all the details.)

#0. HAVE A MAP

Today I’m just going to be talking about stocking hexes. Before you can do that, though, you need the map you’ll be keying.

First, figure out how big you want your map to be. Having worked with a 16 x 16 map with 256 hexes, I’ve concluded that (a) it’s bigger than it needs to be and (b) it requires a ridiculous amount of prep work. So I recommend that people start with a 10 x 10 or 12 x 12 map: 100 or 144 hexes are substantially more manageable and the map will be more than big enough.

Second, place the home base for the PCs in the center of the map. (This way they can go in any direction without immediately riding off the edge of your prep.)

Second, place the home base for the PCs in the center of the map. (This way they can go in any direction without immediately riding off the edge of your prep.)

Third, grab a copy of Hexographer and lay down your terrain. I recommend large blocks of similar terrain, which can then immediately double as your regions. (Remember that any individual hex is huge. Just because you threw down forest as the predominant terrain type doesn’t mean there can’t be a lot of local variation within it.)

I also recommend having two or three different types of terrain immediately adjacent to the home base: If the PCs go north, they enter the mountains. If they go west, they enter the forest. If they head south or east they’re crossing the plains. (It gives a clear and immediate distinction which provides a bare minimum criteria that the PCs can use to “pick a direction and go“.)

Fourth, throw down some roads and rivers. You’re done.

#1. BE CREATIVE, BE AWESOME, BE SINCERE

Before we get into any tips, tricks, shortcuts, or cheats, first things first: Do some honest brainstorming and pour some raw creativity onto the page.

The neat ideas you’ve been tossing around inside your head for the past few days? Everything your players think would be cool? Everything you think would be cool? Everything you wish the last GM you played with had included in the game?

Put ’em in hexes.

Then think about the setting logically: What needs to be there in order for the setting to work? What do you want the setting to have?

Get ’em in hexes.

Bring your creativity to the table. And make sure everything you include is awesome because life is too short to waste time on the mediocre or the “good enough”.

Finally, throughout this entire process be sincere. I think it’s really important to stay true to yourself when you’re doing design work: You have a unique point of view and a unique aesthetic. Even when you’re bringing in inspiration or material from other sources, apply it through your own perspective and values.

#2. JUMP AROUND

It can be useful to start at hex A1, go to hex A2, and then systematically proceed on through the A’s before starting the B’s.

But if you’re working on A3 and you get a cool idea that belongs on the other side of the map, don’t hesitate: Jump over there and key it up in hex F7.

This is not only useful from a practical standpoint: It also feels great when you get to column F and discover three-quarters of the hexes have already been filled.

#3. STEAL

Okay, you’ve filled a couple dozen hexes, but now you’re starting to run out of ideas. What next?

Steal.

If you’re reading this blog, I’m guessing you’ve got a stack of modules that you’ve collected over the years. Go pull your favorites off the shelf and start plopping them down into your hexes.

By simply expanding the distances between locations in B2 Keep on the Borderlands, for example, I was able to fill six hexes: The Keep, the Caves of Chaos, the Mound of Lizard Men, the Spider’s Lair, the Raider Camp, and the Mad Hermit’s Hollow.

By simply expanding the distances between locations in B2 Keep on the Borderlands, for example, I was able to fill six hexes: The Keep, the Caves of Chaos, the Mound of Lizard Men, the Spider’s Lair, the Raider Camp, and the Mad Hermit’s Hollow.

Additional locations in the ‘crawl include Caverns of Thracia, The Sunless Citadel, S3 Expedition to the Barrier Peaks, G1 Steading of the Hill Giant Chief, B3 Palace of the Silver Princess, Temple of Elemental Evil, Gates of Firestorm Peak, L3 Deep Dwarven Delve, Return to White Plume Mountain, DLE1 In Search of Dragons, and Forge of Fury. (Quite a few of those supplied multiples hexes.) Plus stuff from the Book of Treasure Maps 1 & 2, Book of Ruins, Touched by the Gods, Supplement II: Blackmoor, The Book of Taverns, quite a few 0onegames products, and The Secrets of Xendrik.

Having 20+ years worth of collecting to fall back on is nice, of course. But even if you don’t have that kind of gaming library, you can find a ton of stuff online for free. And I did: The One Page Dungeon contest is basically an all-you-can-eat smorgasboard for this sort of thing. Dyson Logos has oodles of gorgeous maps. I also pulled a ton of great stuff from Rust Monster Ate My Sword.

#4. STEAL MORE

No, seriously, go steal stuff. Pillage and loot with wild abandon.

For example, I own an almost complete run of Dungeon magazines. Not every Dungeon adventure is appropriate for keying a hex, but a lot of them are location-based (or contain locations that can be ripped out).

For example, let’s flip open Dungeon #65.

For example, let’s flip open Dungeon #65.

(1) “Knight of the Scarlet Sword”. This adventure details the Village of Bechlaughter and the magical silver dome in the center of the village which serves as home to a lich. Use the whole village or just use the dome.

(2) “Knight of the Scarlet Sword” also contains the Caves of Cuwain — the tomb of a banshee. Another location that can be used as a key entry.

(3) “Flotsam” is a side trek featuring a couple of pirates who pretend to be legitimate merchants; they lure people onto their ship by offering legitimate passage and then rob them on the high seas. Not hex key appropriate, but what if the PCs found this ship — and its weird, seemingly crazy crew — just sitting in the middle of the forest. Might be workable: Make it a witch’s curse or a strange haunting. Or just crazy people.

(4) “The Ice Tyrant”. Heavily plotted adventure, but you can start by ripping out the fully-mapped Lodge and placing it along any convenient road that needs an inn.

(5) “The Ice Tyrant”. Also contains a map for a Sentinel Tower occupied by evil dwarves.

(6) “The Ice Tryant”. Finally, the Keep of Anghanor — guarded by a white dragon and containing a bunch of bad guys.

(7) “Reflections”. A side trek involving a cavern where a will ‘o wisp has imprisoned a gibbering mouther.

(8) “Unkindness of Raven”. Location-based adventure triggered by stumbling across Crawford Manor while wandering through the wilderness. Plop it in.

(9) “The Beast Within”. Location-based adventure triggered by stumbling across a werewolf’s cottage in the wilderness.

And there you go. One random issue of Dungeon and you’ve got 9 hexes keyed. Pick up a dozen issues and you could probably key a full 10 x 10 hex map entirely from the magazine.