Gary Gygax, Dave Arneson, Brennan Lee Mulligan, and Justin Alexander all run their campaigns differently than you do.

What do they know that you don’t?

And what are the five keys you need to unlock these epic campaigns for yourself?

Gary Gygax, Dave Arneson, Brennan Lee Mulligan, and Justin Alexander all run their campaigns differently than you do.

What do they know that you don’t?

And what are the five keys you need to unlock these epic campaigns for yourself?

If I had a nickel for every time I’ve reviewed a D&D 5th Edition Starter Set, I’d have four nickels. Which isn’t a lot, but it’s a weird that it’s happened four times.

This particular starter set is Heroes of the Borderlands, and it’s designed to introduce new players to the D&D 2024 version of the game. I’ve previously reviewed:

If you’ve read those reviews, then you know that what I’m looking for in a starter set is a complete game. I feel strongly that no one should buy a game, take it home, and then discover that it’s just a disposable advertisement for the game they should have bought in the first place.

I also feel strongly that an effective starter set desperately needs to do a superb job of introducing new Dungeon Masters to the game. When new players buy a D&D starter set, they’re expecting it to show them how to play their first roleplaying game, and the entire experience is lynchpinned on the DM. You can’t just cross your fingers and hope they’ll figure it out on their own.

Last, but not least, the introductory adventure should (a) ideally be multiple adventures and (b) show off the unique strengths of tabletop roleplaying games. If your premiere gateway product is a railroaded nightmare or makes D&D look indistinguishable from Gloomhaven, then something has gone wrong.

(You also get bonus points if you include some sort of solo play option, so that someone opening the box on Christmas morning can immediately dive in, get a little taste of what RPGs can be like, and get excited enough to gather their friends ASAP for a proper session.)

With these principles as our guiding light, I concluded that Lost Mine of Phandelver, in the 2014 Starter Set, was quite possibly the best introductory adventure ever published for D&D (in no small part because it was actually a full-blown campaign). The rulebook in that set was also notable because it included enough source material (monsters, magic items, and so forth) that it felt like a DM could continue designing and running their own adventures even after completing the included adventure. It was hampered only by the lack of character creation rules.

The Essentials Kit, in 2019, significantly improved the rulebook by including character creation, but lacked the same robust selection of monsters and magic items. The Dragon of Icespire Peak adventure was a solid entry, but also a bit of a downgrade from Lost Mine of Phandelver. Combining the Starter Set and the Essentials Kit, on the other hand, would give you a near perfect introductory set.

In 2022, Dragons of Stormwreck Isle tried to supplant both its predecessors… and failed. Character creation was gone, the rulebook was gutted, and the adventure was mediocre at best. This was a disposable and disappointing set.

In the end, Frank Menzter’s 1983 D&D Basic Set remained the reigning champion of D&D introductory sets.

Can Heroes of the Borderlands dethrone it?

OPENING THE BOX

The core content of Heroes of the Borderlands is contained in the Play Guide, which serves as the rulebook, and three adventure booklets: Keep on the Borderlands, Wilderness, and Caves of Chaos.

Then you’ve got the bling:

It’s a lot of bling! And most of it is fully illustrated. You can definitely see where the $50 MSRP went.

RULEBOOK

In looking at the Play Guide, I think there are two key questions:

And, obviously, these questions are pretty intertwined with each other.

Well, let’s start at the beginning: The sequencing of the Play Guide is quite poor. For example, they try to describe all the Actions in the game before they explain how Turns work, which is hopelessly confusing. And they mention D20 Tests like a dozen times before telling the reader what they are. Simple procedures are needlessly cluttered up with exceptions, and the exceptions being based on rules that don’t appear until later doesn’t help.

At a more fundamental level, the Play Guide, following the lead of the 2024 Player’s Handbook, is a glossary-based rulebook. Glossary-based rulebooks kinda suck for a multitude of reasons, but they’re particularly disastrous at teaching new players how to play a game: Instead of presenting the rules as a series of instructions, they instead decouple the mechanics and expect the reader to reassemble the procedures of play. In addition to being inherently confusing, they’re also prone to making glaring mistakes, and the Play Guide inherits a bunch of mistakes from the core rulebooks without blinking an eye.

For example, in the main text the Influence action is defined as making a Charisma check to alter a creature’s attitude. In the glossary, however, the Influence action is defined as making a monster do something you want and the monster’s attitude is now a modifier on the check. If you’re an experienced DM, this is the kind of thing that just makes you sigh and shake your head. But it’s a needless booby trap for a brand new player just trying to figure out the game.

(The rules that directly contradict each other probably also distracted you from the Influence action only being usable on monsters, not NPCs. Which is just a straight-up mistake.)

You’ll also discover that core game concepts are missing from this rulebook. Proficiency bonuses, for example, have been baked into the pregen character sheets without any explanation of what they are or where they come from.

So, would I want to learn D&D from this book?

No. It’s sloppy, poorly organized (particularly for a first-time player), and incomplete.

And how well does this function as an actual D&D rulebook? Or is this just disposable trash designed to be thrown away after playing it once?

The answer here is a bit more nuanced, because the box does, for example, include a pretty diverse array of monsters, while the adventures books, as we’ll talk about in a moment, make a couple of half-hearted attempts to encourage the would-be DM to create their own adventure content. The limited character creation rules, on the other hand, have to be a pretty large ding, and the overall vibe is definitely disposable.

Most damning for me, personally, is that if you learned the game from this rulebook and then joined a group playing with the Player’s Handbook, you’d immediately be blindsided by the missing core concepts. So it’s very limited as a stand-alone experience, but also inadequate as a pathway to learning and playing the full game. It’s just a subpar manual across the board.

THE ADVENTURES

The three adventure booklets are a lot more exciting.

A single DM can take the three adventure booklets — Wilderness, Keep on the Borderlands, and Caves of Chaos — and use them as a traditional adventure or mini-campaign. But Heroes of the Borderlands also offers a more radical proposal: You can give each adventure booklet to a different player, with each one serving as the DM whenever the PCs go to the region covered by their booklet.

This is insanely cool!

First, it’s incredible to see such a big, daring concept in a product aimed at new gamers. It really challenges the engrained expectations of the RPG hobby, and even if only one table in a hundred takes the bait and begins experimenting with shared campaign worlds and other alternative structures for organizing their campaigns, that’s still a triumph.

Second, it’s such a great way to encourage more new players to try out the role of the Dungeon Master.

I’m assuming Justice Ramin Arman, the lead designer on Heroes of the Borderlands, was the one to come up with this concept and he deserves all the kudos in the world for it. This kind of thinking — and a willingness to experiment — is vital if you’re serious about growing the hobby.

As far as the adventures themselves go, there’s a goodly amount of adventure material in each one (you can expect to run this boxed set for several sessions) and, in terms of quality, it’s solid stuff.

For each adventure booklet, you start by pulling out the poster map for the region and laying it on the table:

Then you simply ask the players, “Where do you want to go?”

In the case of the Wilderness, as seen above, the choices are:

In this case, if the players choose to go to the Keep or the Caves of Chaos, you would swap to those adventure booklets (although possibly only after triggering one or more Trail encounters on the way there). Otherwise, you simply flip to the matching sub-region in the adventure booklet and run the encounters and/or locations detailed there.

Everything about this great. It’s a simple structure for a novice DM to grok and use. It empowers the players without overwhelming them. And the adventure material is lightly spiced with just enough clues, job offers, and the like to link the various regions together and give the players the opportunity to start pursuing specific goals.

(Although if they just keep pointing at stuff and saying, “Let’s go there now!”, that works, too.)

QUIBBLES

I do have a few quibbles with the adventures, though.

For starters, if you’re going to suggest that separate DMs could each take a separate adventure booklet and swap their PCs in and out, then you need to make sure that none of the booklets have spoilers for the other booklets. There aren’t too many of these, but they do crop up. Notably, several of these are actually phrased as tips or reminders: “Hey! Don’t forget the huge spoilers over in the Caves of Chaos!” Normally that would actually be good praxis, but here it’s fighting one intended use of the booklets.

The biggest misfires of Heroes of the Borderlands, in fact, are often places where it seems to be fighting with itself.

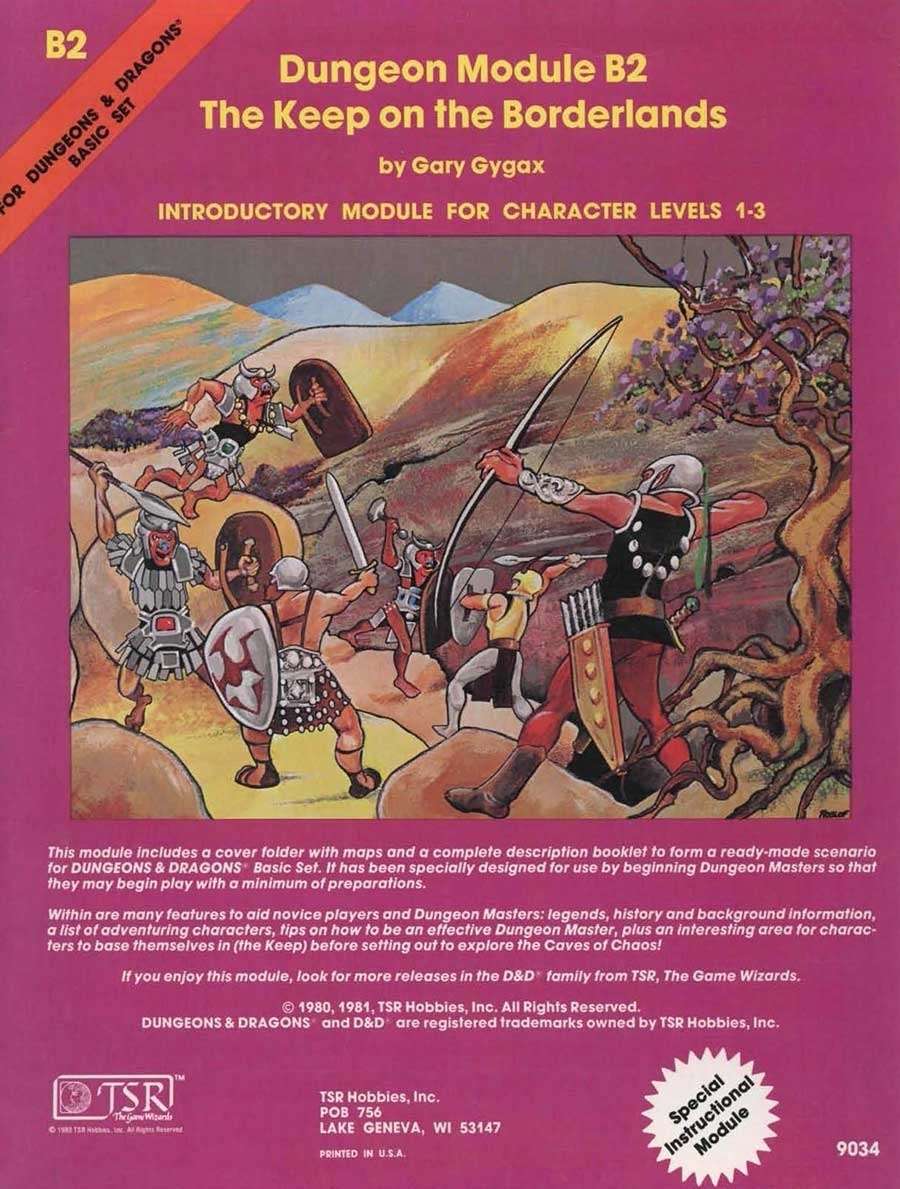

For example, the original Keep on the Borderlands adventure by Gary Gygax on which Heroes of the Borderlands is based, is, in my opinion, a brilliant introductory adventure in large part because of the moment when the PCs step into a gorge and behold the Caves of Chaos for the first time: A dozen different cave entrances line the gorge’s walls! Which one do you want to enter?

For example, the original Keep on the Borderlands adventure by Gary Gygax on which Heroes of the Borderlands is based, is, in my opinion, a brilliant introductory adventure in large part because of the moment when the PCs step into a gorge and behold the Caves of Chaos for the first time: A dozen different cave entrances line the gorge’s walls! Which one do you want to enter?

The very first action that the PCs take in the adventure is a choice. And that choice will completely reshape how the adventure plays out. It’s a moment that immediately tells a new player everything they need to know about how an RPG is supposed to work.

Initially, it seems like Heroes of the Borderlands is going to capture that same magic! “Look at this map! Just point at where you want to go!” it says. In fact, it does it three times over! Once for the Caves, again for the Wilderness, and again for the Keep!

… but then the authors immediately tell the first-time DM to take the choice away and tell the players where to go. For example, from the Caves of Chaos booklet:

Cave A functions as a tutorial with helpful sidebars. If this is your first time as the DM, encourage the players to start there.

And you can see that the intention is good: We prepped a tutorial for you!

But look at the effect it has! Instead of teaching the DM to give the players free choice, you tell them to take it away. Instead of new players having that defining moment of realizing THE CHOICE IS YOURS, their first moment in the game is instead the DM telling them what their choice will be.

First impressions matter. Wizards of the Coast has this immense privilege of being the gateway to the RPG hobby. It’s a shame that they so often prove utterly incompetent at introducing new players to the game: Not just failing to help them, but actively going out of their way to teach them the wrong things to do.

In any case, as I mentioned before, the wealth of adventure material is generally well done and supported with a plethora of poster battlemaps.

There are a few encounters that are conceptually weird: A huge forest fire that’s also surprisingly short-lived. An NPC hireling that follows video game logic (just standing around until the players click him and tell him to fight, then returning to his spawn point where the players can fetch him again). A bank that charges 10% interest per DAY. An unintentionally hilarious bit where three hobgoblins and their four goblin followers are planning to besiege a castle that has dozens of armored knights defending it.

I think my favorite along these line is: “We’ve set up a town where you can’t buy rations because we didn’t want to include rules for that, but we’re going to frame up a ‘your hungry RIGHT NOW’ encounter where you have to immediately choose which color of pine nuts you’re going to eat, and if you choose wrong you’re going to be POISONED!”

Beyond these oddities, the material in general does suffer a bit from a lack of depth. I think the intention was to make it easier for 8-year-olds to run the game (even though the box says 12+), but I’m not sure it was the right approach. In my opinion, it’s easier to run a scenario when you understand WHY stuff is happening in the scenario. So shallow material occasionally plagued by illogical nonsense tends to leave a lot of booby traps

There are other booby traps, too, like a quest to make a map with more details than the maps given to the DM (which puts the new DM in a tough spot to start improvising the necessary details) and milestone leveling guidelines in each of the adventure booklets that, as far as I can tell, are simply incompatible with each other. (Not inconsistent. Incompatible.)

But these are, as noted, quibbles and isolated incidents. Everything here is serviceable enough. It’s mostly frustrating because it’s so close to being a lot better than the “this is OK” that it ends up being.

MISSED OPPORTUNITIES

Along those same lines, there are some pretty big missed opportunities in Heroes of the Borderlands.

For example, at the end of the Wilderness book, there are eight random encounters given for each of the four sub-regions, for a total of thirty-two encounters. With just a little bit of cooking and a few hundred words, this material could have been coherently presented as an example of how to restock and expand the scenario.

Instead, it’s presented without any structure at all, and just kind of assumes that the new DM will magically know how to use random encounters.

Similarly, every cave in the Caves of Chaos book includes utterly inadequate “guidelines” for adjusting encounter difficulty. For example:

You can add monsters, such as allied Goblin Warriors, to the cave to make this scenario longer and more difficult, or you can remove some monsters to make it easier and shorter. One or two Hobgoblin Warriors might be out on a patrol elsewhere.

The new DM is given no indication of how or when or why they would want to adjust the difficulty. And if they do, for example, decide to make this lair more difficult… well, how many Goblin Warriors should they add, exactly? Two? Four? Eight? There are no encounter guidelines in this boxed set, so they’re shooting in the dark. Hope you don’t screw up and kill everybody!

Here’s another unforced error:

The characters can leave the Caves of Chaos any time they choose, provided they aren’t inside a cave or engaged in combat. If they return to a cave later, it is as they left it.

Now, I wouldn’t necessarily advise brand new DMs to run fully dynamic dungeons with enemies building fortifications, adversary rosters, restocking events between visits, and so forth. But I also wouldn’t go out of my way to tell them NOT to do that. Just because they’re not ready to take the next step, it doesn’t mean you should steer them onto the wrong path!

And if you’re going to include woefully under-documented suggestions for monsters DMs can add to the caves, why not include the idea of using those same monsters as a way of restocking the caves for future visits or brand new adventures?

BLING!

I’ve already listed all the additional bling in the Heroes of the Borderlands. The production values on this stuff is top-notch. It’s very attractive.

But I have to admit I have a bias against unnecessary knick-knacks. I understand the desire to add a lot of stuff to make the cover price seem “worth it,” but I just think it’s a bad idea in an introductory product to create the perception that, for example, you “need” an equipment card for every piece of equipment the PCs are carrying.

This is particularly true when the desire to have some physical component actually gets in the way of teaching new players how to actually play D&D.

But if you like bling, it’s very nice bling.

THE VERDICT

Spreading Heroes of the Borderlands out on the table in front of me, what’s the final verdict here?

Well, I can’t recommend the rulebook to anyone. Its primary job is to teach new players and DMs how to play the game, and it’s really bad at doing that.

I’m going to give the adventures a C+. It’s solid material and lots of it, and I have to give credit for the bits where the booklets dare to dream big. (Even when they’re simultaneously cutting the legs out from under a lot of those dreams.)

Combining these things together, I’m going to give the total package a C-. (I’d probably give it a D+, but I’m going to bump it up a notch because all the bling does add tangible value.) As a Starter Set for D&D, this mostly gets the job done, and there are places where true genius shines through, like the shared DMing duties and point-at-the-map introduction to exploration and adventure. I wish they’d fully committed to some of those ideas, spent more time teaching new DMs essential skills, and spent less time sabotaging both themselves and the new players trying to learn the game.

GRADE: C-

Lead Designer: Justice Ramin Arman

Designers: Jeremy Crawford, Ron Lundeen, Christopher Perkins, Patrick Renie

Publisher: Wizards of the Coast

Cost: $49.95

Page Count: 96

ADDITIONAL READING

Keep on the Borderlands: Factions in the Dungeon

Johann asks:

[I’m running] an open table with three DMs. I was wondering about the information and knowledge players have and seek out. We ask one player to write kind of like a journal entry for the others, but only a very few dedicated people actually read these. The same goes for the wiki; only a few people look into this.

While we want to keep a low barrier to entry, we also think some information is critical for those players who return often, such as factions, their goals and issues, or rumors placed by us.

How do you handle this? Do you do kind of a recap at the beginning of the session?

Information flow in an open table is different from a dedicated table. In a dedicated table, the expectation is that all players will know everything that’s going on.

An open table is paradoxical because you’ll simultaneously have many more players than a dedicated table, but in many ways each individual player’s experience is more like a Campaign of One: There is no single, unified, overarching story of the group. Instead, each individual character is experiencing their own, individual story.

“How do I know what happened to Bill last session?” Well, either you were there or Bill told you or you asked Bill about it. That’s entirely about what the characters doing. As the GM, you don’t need to take on responsibility for any of that, beyond maybe giving the players a forum for communicating with each other away from the table (e.g., a Discord server or wiki). Either the players will share information with each other or they won’t. Either one is fine.

Other information, of course, will be more publicly known. I think of this as headline news. If somebody burns down the village church, for example, that’s something everybody in town is going to know about. Whether it was an NPC or a PC or a natural disaster that burned the church down, for this type of stuff I’ll prep a short, often bullet-pointed, bulletin and send it out to all of the players. The most effective method of distribution will depend on how you’re organizing your open table. For me:

When you should cycle stuff off your Current Headlines list seems to be a bit more art than science, in my opinion. It depends partly on how vital/important the information is, how often people are playing, and also a general desire to not.

But it’s easy to imagine completely different options, too. You might actually write up the front page of a newspaper, for example, as something you can give as a handout or physically post in the game store where you’re playing. Or you could keep a list of headline news, but find more organic ways to weave it into your downtime procedures (rather than just reading out the list).

SCENARIO HOOKS

Of course, there’s also other types of information to be shared about the world. At the other extreme, you have scenario hooks, and this is where things can operate very differently at an open table.

For example, consider a treasure map revealing the location of the Temple of the Ancients. At a dedicated table, if a PC finds the treasure map, then they have it. At an open table, though, a player might find that map… and then literally never play again.

Under these conditions, the inverted Three Clue Rule breaks down due to information loss:

If the PCs have access to ANY three clues, they will reach at least ONE conclusion.

If you prep three leads pointing to the Temple of the Ancients, but then one of them exits the campaign, you’ve effectively broken the rule. In fact, it’s quite possible for all three leads to vanish! And even if they don’t, the rule can still break down due to the diffusion of players: The rule works partly through redundancy, partly through repetition, and partly because of what happens when the players combine multiple pieces of information together. But if each of your three clues is found by a different PC and those PCs rarely or never actually meet each other, the practical effect can be far closer to having just one clue three times over, rather than three clues reacting with each other and backing each other up.

Faced with this dilemma, it can be tempting to want to “liberate” the scenario hooks: Bill finds the treasure map, and the treasure map is added to some kind of group repository where any group can grab that lead and pursue it. (And you could imagine any number of diegetic explanations of this: For example, maybe all of the PCs are members of the Pathfinder Society or Delver’s Guild and are required to make full reports to the local branch office.)

Balanced against this, though, is the fact that secret knowledge is fun and all kinds of fun secondary and tertiary game play can emerge from it. (For example, maybe Bill offers to auction off the treasure map to the highest bidder. Or it motivates Bill to organize a secret expedition. Or someone else learns the map exists and tries to steal it from Bill. Some of the most memorable moments from my open tables involve players horse-trading information and getting excited when they get to reveal secrets to other PCs.)

Taking a step back, the broad situation here is that I have a scenario (e.g., the Temple of the Ancients) and I don’t want to just throw out all of that prep because the three clues pointing to that scenario randomly got misplaced in the dynamics of the open table.

There are generally some straightforward solutions for this:

This isn’t to say that you should stop including clues and leads connecting adventures in your open table. This additional layer in the campaign creates different ways for the PCs to interact with the world, creating a far more dynamic and interesting situation. But it’s probably best to think of their effect as being far more localized than in a dedicated campaign: The primary effect is going to be to enhance and shape the experiences of individual characters, rather than being the primary backbone of the campaign as a whole.

THE OTHER STUFF

Somewhere between headline news that everyone hears about and individual nuggets of information like a treasure map that are accessed by specific individuals, there’s a potentially vast middle ground of stuff happening in the campaign world that the PCs might learn about.

A good example of this are faction downtime actions, as discussed in So You Want to Be a Game Master. The quick version is that you have a bunch of factions in the campaign world, they’re doing stuff, and the fallout from that stuff should be vectored so that it intersects the PCs.

(Rumors, job offers, and random encounters are typical examples of how this stuff can be vectored into the PCs. For example, a couple of gangs might have gotten into a turf war, and the PCs might hear about the gang violence or witness a gang shooting on the street or get hired by one of the gangs to assassinate the leader of the other gang or have one of their contacts get recruited by a gang.)

In a dedicated campaign, you can make a tick on a faction clock, figure out how to vector it into the PCs, and check it off your list: Job done! Good work!

If you do that at an open table, of course, the vector of the faction’s action will only intersect a tiny percentage of the players. Instead of sending shockwaves through the campaign, the faction’s actions are creating tiny little ripples.

To solve this you need to either escalate the faction’s action to headline news or you need to generate multiple vectors, likely keeping the faction action on your To Do list for three or four sessions so that multiple groups (and lots of players!) interact with the fallout.

THE SETTING LORE

A final consideration is bringing players up to speed on the campaign’s lore so that they can create their characters and understand what’s going on.

Here, again, I think you’ll find it most useful to think of the open campaign as many different solo campaigns. In other words, even at session fifty of the open table, a new player is effectively joining a brand new campaign. Imagine that you ran a dedicated campaign in Waterdeep and now you’re running a new campaign in Waterdeep with a completely different group of players: You would need to introduce these new players to the setting, but you wouldn’t spend a bunch of time talking about everything that happened in the previous campaign. The same thing is true of the open table.

Since you want quick character creation for an open table, I generally recommend having no more than a two-page handout and/or a five-minute spiel to orient a new player. In practice, I’ve found that I rarely need to update this. For example, in my Castle Blackmoor open table, the original introduction boiled down to: “There’s a castle and there’s a dungeon underneath it. Adventurers have been going down to explore its depths in the hopes of rescuing Baron Fant, who was kidnapped from the castle by monsters that emerged from the dungeons.”

Lots and lots of stuff happened within the dungeons, but this spiel was largely unaltered until it became common knowledge that Baron Fant had been transformed into a vampire. And even this was, obviously, a pretty minor adjustment: “Adventurers have been going down to explore its depths in pursuit of Baron Fant, who fled into the dungeons after being turned into a vampire.”

What you want to be cautious of is allowing more and more narrative to creep into your spiel. If my Castle Blackmoor campaign had continued, for example, you could imagine the spiel growing over time: “There’s a castle and there’s a dungeon underneath it. The campaign started when it was believed Baron Fant had been kidnapped by monsters that emerged from the dungeons, but it was later discovered that Baron Fant had actually been turned into a vampire and fled into the dungeons. He was later slain, but only after turning one of the adventurers who had gone after him. Lady Eilidh, as she became known, has withdrawn further into the depths of the dungeon, taking with her the vampiric remnants of the hobbit village that was also corrupted by the vampires. It’s currently pixie breeding season, diplomatic relations have been opened with a colony of werelions within the dungeon, and other expeditions continue apace.”

In reality, what I actually did was simplify my spiel: “There’s a castle and there’s a dungeon underneath it, which adventurers have been exploring.”

It wasn’t that current events weren’t relevant, but that information would organically flow to the player through

For similar reasons, having new players generally default to playing characters who are “new in town” (whatever that means for your particular open table) can be very useful. Even if a new PC isn’t actually new in town, thinking in that paradigm can still be a good way of identifying what information is truly essential.

It seems paradoxical, but often stripping down information a new player needs to process before they start playing can often help them not only get oriented faster, but also get them immersed into the lore faster (because they’ll start encountering it through play as a living experience as they build their own personal story).

Review Originally Published May 21st, 2001

With The Tide of Years Penumbra has gone from being one of the premiere D20 companies to being THE company producing D20 supplements – and I include Wizards of the Coast in that assessment. In The Tide of Years Penumbra not only introduces a new set of production values which are better than anything else in the D20 adventure market today, they apply them to a package which offers more material, of higher quality, than almost anything else in the D20 adventure market.

In short: This is good. This is very, very good.

PLOT

In the mists of antiquity there was a mighty empire: Lagueen. Lagueen was built upon the power of the Temporal Crystal, a powerful artifact which allowed the Priests of Ras’tan to unlock the secrets of time. From the ancient past and the distant future, Lagueen was able to harvest the greatest inventions and cultural treasures.

But Lagueen was brought low when a traitorous acolyte attempted to steal the Temporal Crystal. Although thwarted in her effort by a young priest named Jonar, the thief did succeed in activating the Temporal Crystal – transporting herself, Jonar, and the Crystal into the distant future. Unfortunately, without the Crystal, the marvelous society which had been created in Lagueen quickly fell apart. As their structures slowly collapsed from disuse and lack of repair, a landslide was triggered, blocking the end of the river valley in which Lagueen lay. “The river bloated and the valley floor flooded, covering the remains of Lagueen in a shroud of murky waters.” When the thief and priest reappeared, they found themselves at the bottom of an immense lake and quickly drowned.

Enter the PCs, who are, of course, passing through the forest which has grown up around the lake in which Lagueen has sunk. They are approached by the ghost of Jonar, who wants to set things right. The reappearance of the crystal has also triggered a temporal disturbance, slowly reverting the forest to a primeval state. Jonar will lead them through the valley to recover one of the temporal shards which the empire of Lagueen used in coordination with the Temporal Crystal to power their arcane technology. He will also introduce them to a local nixie, who will be able to grant them the ability to breathe underwater.

From here, of course, the PCs must journey beneath the lake – journeying to the sunken city of Lagueen, and (most importantly) the Temple of Ras’Tan in which the Temporal Crystal now lies. The temporal shard will unlock the temple’s ancient doors, but even once they’re inside the PCs will still need to deal with the ancient temporal traps laid in Lagueen’s golden age and the subterranean monsters which have taken up residence within the temple.

Once they reach the crystal, the PCs can return it to its proper place – just moments after the thief took it from Lagueen. This, of course, changes history, which can have one of two effects on the campaign world: First, the PCs’ actions may simply create an alternate dimension in which Lagueen never fell. On the other hand, the PCs may actually change their own world (the effect of this can be minimized by keeping Lagueen as a hidden kingdom, which has deliberately decided to keep its contact with the outside world to a minimum; or you can fully embrace the cataclysmic change).

STRENGTHS

Despite the critical success of their first adventure (Three Days to Kill) and their subsequent D20 products (Thieves in the Forest and In the Belly of the Beast), Atlas Games has not been content to simply rest on their laurels and repeat their past successes. Each new Penumbra product has improved upon the last, and each has taken pains to explore new territory. And this willingness to explore, experiment, and improve has ended up paying big dividends for Atlas Games – and, more importantly, the gamers who have followed their product line.

And with The Tide of Years they’ve raised the stakes one more time: The graphical look of the adventure is better than just about anything else being put out for D20 (and that includes Wizards of the Coast). The amount of material has been doubled over their previous efforts, and the quality of that material remains as high and innovative as ever – not only presenting the adventure itself, but (in the course of that adventure) providing a number of generic resources: New monsters (compsognathus, icthyosaur, monstrous aquatic spider, and time elemental), a new god (Ras’tan, God of Time), a new clerical domain (time), new cleric spells (detect temporal disturbance, dispel temporal effect, scry the ages, hastening of age, and wellspring of youth), new traps (temporal skids and temporal lags), a new magic item (the temporal shard), and the “lost empire” of Lagueen (which, like Deeptown in Three Days to Kill, is generic enough to be slipped into almost any generic fantasy campaign – while, at the same time, being unique and distinctive enough to be a memorable element of that campaign).

WEAKNESSES

The interior artwork, while of high quality, sometimes seems to be skewed from the text. For example, an underwater pyramid is shown – but it’s not the pyramid described in the text, and the characters swimming around it are wearing strange breathing apparatus which is not part of the adventure.

I would have also liked to see Nephew play a bit more upon her time travel theme. A forest returned to the primeval state, time traps, artifacts, and elementals are certainly more than sufficient – but I felt there was still a lot of territory left unexplored.

CONCLUSION

To put it succinctly: The Tide of Years delivers. Michelle A. Brown Nephew should be rightfully proud of her inaugural gaming product, and we should count ourselves lucky to have a company like Atlas Games producing adventures like this one.

Style: 4

Substance: 5

Authors: Michelle A. Brown Nephew

Company: Atlas Games

Line: Penumbra

Price: $10.95

ISBN: 1-887801-98-7

Production Code: AG3203

Pages: 48

While it’s nice that Michelle included a minimally disruptive option for the temporal restoration of Lagueen, I really respect an adventure that’s willing to go big — world-alteringly big! — with its potential consequences. It reminds me of Death Frost Doom, which is tonally almost completely opposed to The Tide of Years, but equally memorable.

The trick, of course, is being able to actually EARN the epic consequences. That can be a very fine line to walk.

For an explanation of where these reviews came from and why you can no longer find them at RPGNet, click here.

In this episode of the RPG series of the Game Design Round Table, hosts Dirk Knemeyer and David Heron are joined by Justin Alexander , a renowned game designer and thought leader in tabletop RPGs. Known for his influential essays and innovative GM techniques, Justin shares insights into the role of the Game Master as designer. They dive into how GMs can connect narrative ideas to mechanics, the philosophies behind crafting memorable RPG experiences, and the challenges new GMs often face. Whether you’re building worlds or running them, this episode offers practical tools and deep design wisdom.