Now that we’ve established the basic tools for pacing in roleplaying games, let’s briefly visit some advanced techniques. This will be by no means an encyclopedic treatment of the subject. In fact, we’ll barely even scratch the surface. But hopefully even a quick exploration of the topic will point us in some interesting directions.

SPLITTING THE PARTY

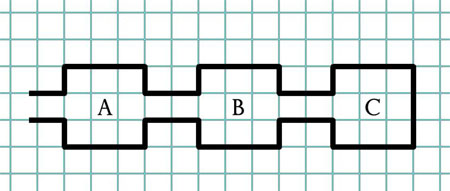

Let’s start with simultaneous scenes: Half the party leaves to explore the abandoned water tower while the other half of the party goes to question Jim Baxter, the farmer with an inexplicable supply of Nazi gold.

On two entirely separate occasions I’ve had a group I’ve been GMing for spontaneously announce that they weren’t going to split up because they didn’t want to make things tough for me. In both cases, I rapidly dissuaded them from their “good intentions”: The truth is, I love it when the PCs split up.

On two entirely separate occasions I’ve had a group I’ve been GMing for spontaneously announce that they weren’t going to split up because they didn’t want to make things tough for me. In both cases, I rapidly dissuaded them from their “good intentions”: The truth is, I love it when the PCs split up.

While it does take a little extra juggling to handle multiple sets of continuity, that slight cost is more than worth the fact that a split party gives you so many more options for effective pacing: The trick is that you no longer have to wait for the end of a scene. Instead, you can cut back and forth between the simultaneous scenes.

- Cut on an escalating bang. (The bang becomes a cliffhanger: “The door is suddenly blown open with plastic explosives! Colonel Kurtz steps through the mangled wreckage… Meanwhile, on the other side of town—“)

- Cut on the choice. (Remember that everything in a roleplaying game is a conversation of meaningful choices. When a doozy of a choice comes along, cut to the other group.)

- Cut on the roll of dice. (Leaving the outcome in suspense. But the other thing you’re eliminating is the mechanical pause in which the dice are rolled and modifiers are added. All of that is happening while something exciting is happening to the other groups. And when they get to an action check—BAM! You cut back to the first group, collect the result, and move the action forward.)

- Or, from a purely practical standpoint, cut at any point where a player needs to look up a rule or perform a complex calculation or read through a handout. There may not have been a cliffhanger or a moment of suspense to emphasize, but you’re still eliminating dead air at the gaming table.

The end result is that effective cuts between simultaneous scenes allow you to easily tighten your pacing, heighten moments of suspense, and emphasize key choices.

CROSSOVER

Once you’ve mastered the basic juggling act of simultaneous scenes, you can enrich the experience by tying those scenes together through crossovers.

The simplest type of crossover is a direct crossover. This is where an element or outcome from one scene appears immediately in a different scene. For example, if one group blows up the arms depot then the other group might hear the explosion from across town. Or Colonel Kurtz flees from one group of PCs and ends up running back to his office… which the other PCs are currently searching.

Indirect crossovers are both subtler and more varied. These are common or related elements in each scene which are not identical. For example, you might have Franklin discover a cult manual bearing the sign of a white cobra while, simultaneously, John sees a white cobra painted on the face of his murdered wife.

An indirect crossover might not have any specific connection in the game world whatsoever: For example, Suzy might ask Rick out for a date at the Italian Stallion on Friday night. Simultaneously, in a different scene, Bobby gets ordered by his police lieutenant to arrange surveillance for a mob boss meeting at the same restaurant at the same time. Suzy and Rick have no connection to the mob or the police, but that’s still a crossover.

This also demonstrates how crossovers can be used to weave disconnected narratives together: Suzy, Rick, and Bobby are all going to end up at that restaurant at the same time. Franklin and John are both going to be launching separate investigations into the white cobra. It’s still not clear exactly how their paths are going to cross, but they’ve definitely been set on a collision course.

This technique can be particularly effective at the beginning of a scenario or campaign: Instead of having the PCs all meet in a bar, you can instead launch them all into separate scenes and then seed crossovers into those scenes to slowly and organically draw them all together.

Another way of using these techniques is to strengthen the role of player-as-audience-member. You know that moment in a horror movie where the audience doesn’t want a character to open a door because they know something the character doesn’t? Hard to do in an RPG… unless the table knows it (because it was established in a different scene), but the PC doesn’t. (This assumes, of course, that your players are mature enough to handle a separation of PC and player knowledge.)

NON-SEQUENTIAL SCENES

It should be noted that techniques similar to crossovers can obviously be used in sequential, non-simultaneous scenes, too. (John sees a white cobra painted on his dead wife’s face and then, later, the PCs discover the white cobra cult manual.) But the specific idea of the crossover is that you’re specifically juxtaposing the two elements both for immediate effect and to tie the simultaneous action together.

For some people, this can easily feel artificial. What are the odds, really, that both the dinner date and the surveillance order are both being made at the same time? One way to work around this is through the use of non-sequential scenes: The scene in which the dinner date is made might take place on Tuesday and the police lieutenant might order Bobby to set up the surveillance on Thursday. But that doesn’t mean we can’t run those two scenes simultaneously at the gaming table.

This non-sequential handling of time is also a good way of avoiding another common speed bump GMs often encounter when splitting the party. It starts when a PC says something like this: “Okay, you guys head across town to search the warehouse! We’ll stay here until David can finish cracking the encryption on this database.”

And then the GM thinks: “Well, it’ll take at least 15 minutes for them to get to the warehouse. So I’ll have to play through at least 15 minutes of activity here at the server farm before I can pick up the action over at the warehouse.” But that’s not necessarily true. There’s no reason you can’t run the warehouse search and the server farm stuff simultaneously.

I refer to these as time-shifted scenes. For me, personally, the time dilation on these scenes usually isn’t significant in and of itself. The point is merely to take advantage of more effective pacing techniques. A common example is when everyone splits up to take care of personal errands: We know everything is happening at some point on Wednesday afternoon, but I’m not particularly interested in strictly figuring out what happens at 2pm as opposed to 2:15pm. Instead I’m going to cut on the bangs, cut away from the dice rolls, and do all that other nifty stuff.

FLASHBACKS

Flashbacks are another common form of non-sequential scene. Or rather, they’re very common in other forms of media. In my experience, they’re exceptionally rare in roleplaying games.

Unlike a scene that’s been slightly time-shifted, the nonlinearity of the flashback is often a significant feature of its presentation: What it depicts from the past is meant to be either thematically relevant or expositionally revelatory to the current events of the narrative. (Some non-RPG examples would include Godfather II, which is an extensive but relatively straightforward handling of the technique; Memento, which is an almost absurdly complex use of the technique; and Iain M. Banks’ Use of Weapons in which both sets of scenes originate at the same point in time, with one set of scenes moving backwards through time and the other moving forwards through time.)

Flashbacks and non-sequential scenes in general do require a careful handling of continuity. This is usually a mixture of setting things up to avoid continuity errors ahead of time and also a willingness by everyone at the table not to deliberately violate known continuity. (“I call him on my cellphone!” “Okay, but we already know he went to the warehouse regardless of what you said on the phone call. So play it accordingly.”) The occasional retcon may be called for if things fall seriously out of joint, but that’s obviously not a desirable outcome.

The advantage of a flashback is that it allows you a lot more flexibility in how you explore both character and situation. In addition to, for example, playing out scenes that took place before play begins, flashbacks can also be used to mitigate or enhance hard scene framing: If you end up skipping over something that turns out to be important, you can simply flash back to it.