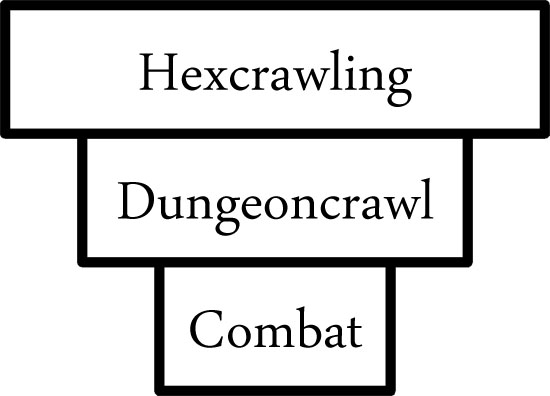

One of the things I talked about in the Game Structures series was the vertical integration of game structures. For example:

The hexcrawling structure delivers you to a hex keyed with a dungeon. Entering the dungeon transitions you to the dungeoncrawling structure, which delivers you to a room keyed with a hostile monster. Fighting the monster transitions you to the combat structure, which cycles until you’ve defeated the monster and returns you to the dungeoncrawling structure.

This can be crudely characterized as: “You explore the hexcrawl so that you can find dungeons. You explore dungeons so that you can find things to kill. You kill things so that you can get their treasure.” This is, obviously, a vast over-simplification. But it effectively drills down to a core structure that exemplifies the basic elements that make these scenario structures tick.

So, in a naturalistic sense, we can ask a wandering hero standing at the gates of a city, “What are you looking for?” But we could look at the same question through a structural lens and ask, “How can we vertically integrate the urbancrawl with other scenario structures?” (And what can that tell us about how we need to structure the urbancrawl itself?)

The structure “above” the urbancrawl is pretty easy to figure out: A hexcrawl brings us to the city, delivers us to the gate, and brings us right back to the question, “What are you looking for?”

Which turns our attention to the structure under the urbancrawl. And for that, let’s start by considering existing structures that we could stick in there.

URBANCRAWL TO DUNGEON

What if we treated an urbancrawl just like a hexcrawl? It delivers you to location-based adventures using a dungeoncrawl structure.

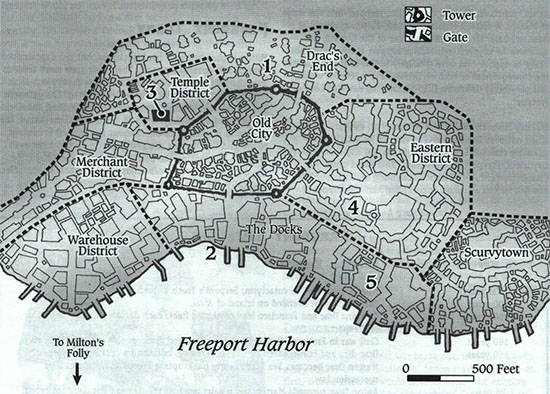

This sort of structure could work well for a Ptolus-style or Waterdeep-style “dungeon under the city” scenario, where the goal of your urbancrawling is to find new and potentially lucrative entrances to the city’s literal underworld.

But while this hypothetical structure could serve as an intriguing patina for a megadungeon campaign, it seems to be primarily interested in providing an alternative exit from the urban environment. What I’m interested in, on the other hand, is finding a structure for actual urban adventuring.

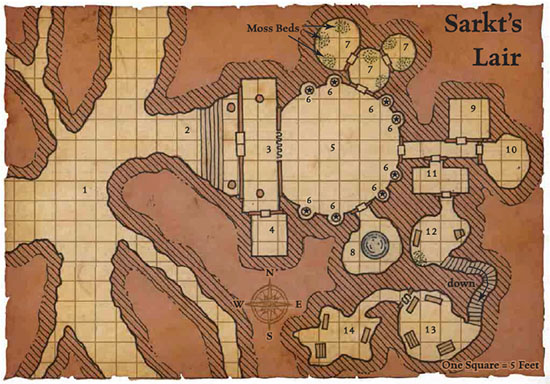

Of course, we wouldn’t necessarily need to do literal dungeons: We could deliver up vampire dens or mob houses or whatever. The mental stumbling block I run into, though, is how to reliably trigger these from simple geographic movement in an urban environment. (But it’s definitely something to keep in mind.)

URBANCRAWL TO COMBAT

What if we treated the urbancrawl just like a dungeon? You crawl into a neighborhood and it triggers a combat encounter just like entering a dungeon room.

The problem I see here is contextualizing this string of violence into something interesting. In a dungeon there is an immediate, physical contiguity which can be used to bind multiple encounters together: The goblins in area 4 are working with the other goblins that can be found in areas 5-10.

By contrast, an urbancrawl is distinct from a dungeoncrawl in that it is presenting selected elements of interest from a much larger pool of information. (As opposed to the dungeoncrawl, which generally presents everything inside the dungeon complex.)

Which isn’t to say, of course, that you couldn’t figure out a way to contextualize urbancrawl combat encounters. For example, if we key a vampire in Lowtown and a vampire in Empire Villa it wouldn’t take much imagination to assume they’re both based out of the same blood den. But since that connection is non-geographical, we would need to figure out a way to “escalate” from the ‘crawl-triggered vampire encounters to the blood den.

(This becomes necessary because movement in a city is, generally speaking, not limited.)

It strikes me that this urbancrawl-to-combat structure would probably work really well for a Dirty Harry-style cop campaign: The ‘crawl becomes your patrol, with the various encounters triggered by the ‘crawl serving as potential hooks into larger investigations.

URBANCRAWL TO MYSTERY

Which brings us to urbancrawls triggering mystery scenarios.

A natural image to pull up here is the cop out on patrol: They walk the streets, spot something suspicious, and the investigation of a crime is triggered. For similar reasons, this might be an  interesting structure to explore for a superhero campaign: The classic “Master Planner” story from Amazing Spider-Man #31-33 was triggered by Spider-Man simply spotting some burglars trying to steal atomic equipment and then following a string of clues that eventually led him to an underwater base hidden in New York’s harbor.

interesting structure to explore for a superhero campaign: The classic “Master Planner” story from Amazing Spider-Man #31-33 was triggered by Spider-Man simply spotting some burglars trying to steal atomic equipment and then following a string of clues that eventually led him to an underwater base hidden in New York’s harbor.

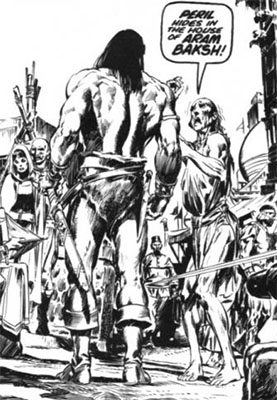

This sort of “walking the streets and having something mysterious bump into you” is also quite popular in classic sword and sorcery literature, however. Robert E. Howard uses it in a number of Conan stories, for example, including “Shadows in Zamboula” which opens with a quivering voice declaiming that, “Peril hides in the house of Aram Baksh!” as the titular barbarian is walking down a street.

As I mentioned earlier, however, true mystery scenarios don’t play well with a true ‘crawl structure because they’re not holographic in their goals: You can’t solve the second half of the mystery unless you’ve collected the clues from the first half. So let’s lay mysteries aside for a moment and back up a moment.

URBANCRAWL TO LOCATION

“Peril hides in the house of Aram Baskh!”

Actually, I’m drawn back to that quote. Because what’s really happening here is that Conan is being told, “There’s something interesting in the house of Aram Baksh! You should totally check it out.” (The actual character is saying “don’t go in there, it’s dangerous, other people have died”, but from a structural standpoint the hook is saying the opposite.)

So let’s remove the trappings of the “dungeon” concept and instead just deliver up “locations”. That actually sounds familiar: It’s very similar to how hexcrawls work.

So what if we treated an urbancrawl just like a hexcrawl?

If you go exploring through an urbancrawl, what types of locations does it deliver to you? How does it deliver them? Why are you looking for them?

I have no idea. So let’s make a hex map of Ptolus.