LOCATION

- 10560 Moonshine Road; Sebatopol, CA

- You can read the address of the mailbox jutting out over the faded concrete.

- MAILBOX: Prop – Bill from Tomahawk Warehouses

- Up in the California hills. A long driveway drops over the lip of a hill or ridge.

- House itself is shrouded in a little clot of scrappy pine trees.

- Thick, waist-high grasses have grown up in front of the house.

OUTSIDE THE HOUSE

SCLERID PATCH: The front yard is occupied by a sclerid patch (The Strange, pg. 298).

FRONT DOOR: A muddy handprint has been partially smeared on the door.

- Examining – Intellect (difficulty 2): To note that the hand print has a sixth finger.

- Lock: Speed task (difficulty 2)

BACK DOOR: There’s no sclerid patch in the backyard.

- Lock: Speed task (difficulty 2)

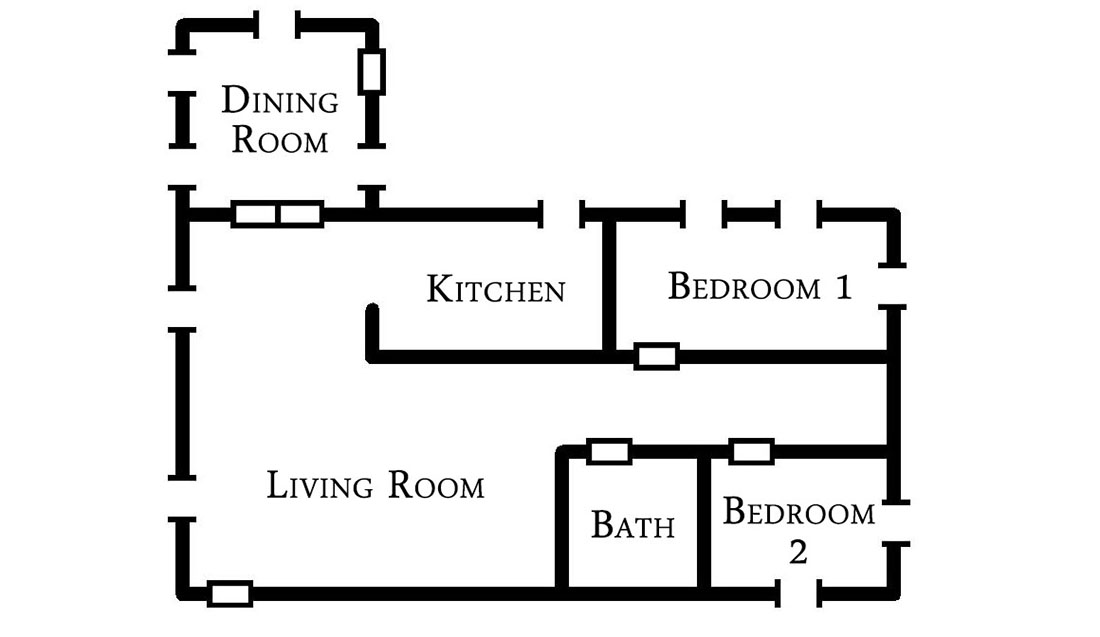

WINDOWS:

- Living Room: Blinds have been pulled.

- Dining Room: Open.

- Kitchen: Open.

- Bedroom 1: Exterior shutters are closed and the windows have been painted over with black paint from the inside.

- Bedroom 2: Exterior shutters are closed. (If opened, you can look in. You can even see the prop stuck between the desk and the window.)

INSIDE THE HOUSE

- A sharp smell of ozone and chemicals in the air.

- A thin, greasy coating on every surface. Kind of a rainbow quality on metallic surfaces.

LIVING ROOM

- An overturned wooden chair next to a chemical-scarred table. An overstuffed chair with strange stains shoved into a corner.

- A gritty, ashy dirt muddying the floor.

RUKIAN CORPSE: In the center of the room.

- Pale, purplish skin. Silvery, metallic hair.

- A pronounced, but narrow ridge encircles the head.

- Blue blood leaks from large, anime-like eyes with metallic irises.

- Intellect (difficulty 4): To identify the corpse as being definitively Rukian (assuming awareness that Ruk exists). It’s out of context, which means inapposite travel.

ANGIOPHAGE: An angiophage rips out of the corpse’s chest and attacks. (The Strange, pg. 258)

- Alternatively, the PCs might see something writhing and wriggling under the corpse’s clothing. (Or the angiophage might emerge when they aren’t looking and ambush them.)

- GM Background: This was one of Enkara-ulla’s assistants. An recursion rupture during the last round of experiments here caused his artificial heart graft to mutate (killing him).

KITCHEN

- A little niche of a kitchen.

- The cupboards are bare. The refrigerator is empty.

DINING ROOM

- There’s no furniture here. Wood-paneled, splinter-laden walls. A crooked light fixture of cracked glass.

- The floor is covered with a strangled patterned, grayish, lumpy shroud.

- Perception – Intellect (difficulty 4): To realize that the “shroud” is very slowly undulating.

DYING THONIK: Covering the floor is a dying thonik, ripped out of the Strange (The Strange, pg. 294). It’ll rear up and attempt to enfold itself around anyone walking across it.

- Out of Context: The thonik is out of context and dying. It is at a disadvantage.

- Cypher Connection: If the thonik can absorb the energy of a cypher (by enfolding someone carrying one), it can tap the latent energy fields left here by Enkara-ulla’s experiments and re-energize its connection to The Strange. Dim, ghost-like fractals will dance through the air and the thonik is considered by in the Strange (see Modifications in its stat block).

BATH

DOOR: The door has been nailed shut.

- Might (difficulty 5): To break the door down without removing the nails.

SCLERID EXECUTIONER: A human woman. Huge, sclerid vines with acid-tipped stingers grow out of her skin (ripping through her clothes and distorting her features) to obscene lengths. (The Strange, pg. 299)

- GM Intrusion: The sclerid executioner breaks through the door (perhaps just before they can remove the last nail).

INSIDE THE BATHROOM:

- Toilet smashed, spilling dirty water across the floor.

- Shower rod hangs askew from the wall, sending a tumble of plastic curtain cascading across the floor.

- Bath tub is full of water with a thick, viscous green slime floating atop it in ropy patches.

GM Background: Another assistant of Enkara-ulla. She was infected by the sclerid patch outside. Enkara-ulla’s guards managed to bulrush her into the bathroom and then nail the door shut.

BEDROOM 1

- Several large, thick cables dangle from outlets incongruously placed halfway up the walls. The paint is mottled and discolored. Dark stains mottle carpet that may once have been cream.

- In the center of the room, there is a four foot high, bullet-shaped case of gleaming chrome. Atop the chrome case, rotating in opposite directions, are two large dials. Petal shaped holes have been punched through the metal of the dials, and heavy-looking weights fall in a perpetual, eye-bending loop within each petal.

PERPETUAL MOTION ENGINE (Level 5): A perpetual motion engine doesn’t require fuel. It attached to something capable of doing work (and properly brace), the engine can deliver up to 300 horsepower for up to a day (which is considered one use of the artifact. If the engine is depleted, fixing it to work condition is an Intellect task (difficulty 5) and several hours in a shop. (Depletion 1-3 in 1d100)

- Studying the Machine – Intellect task (difficulty 3): Identifies the machine as a perpetual motion engine. Several parts inside the machine still have stickers on them indicating that they were purchased from Eschaton Electronics in the Mission District of San Francisco.

- Removing the Machine: It has been bolted to the floor, but it’s relatively trivial to remove it.

CABLES: It’s clear that there were once connected to a large number of machines. (There are matching indentations in the carpet.) One of the cables is a Rukian umbilical.

DARK STAINS: Machine oil. (Although someone touching it receives a painful, but not particularly harmful, electrical shock. If the perpetual motion machine is removed from the room, this effect stops.)

GM Background: This room was the heart of Enkara-ulla’s testing apparatus here in the house. He used the perpetual motion machine as an engine for powering them (after discovering that the power grid effectively grounded out the recursion ruptures if he connected the machines to it). The recursion rupture machines have been removed, but Enkara-ulla left the perpetual motion machine (having no further use for it).

BEDROOM 2

- There’s a table in the center of the room and a small, antique writing desk sitting underneath one of the windows (to take advantage of the view out of the front of the house). There’s a scattering of miscellaneous papers on the table, and a few stuffed into

PAPERS: An inspection of the papers makes it clear that these are just the remnants of much more extensive files that were kept here. (Somebody cleaned it out and left garbage behind.) There is one thing of interest though; it’s fallen off the side of the desk and is resting on the window ledge behind it.

EVENT: PACKAGE DELIVERY

At some point while they’re exploring the house, the PCs will hear a blood-curdling scream from the front yard.

- USPS Mail Carrier (Level 2): He’s arrived to deliver a package and unwittingly stumbled into the sclerid patch.

- GM Intrusion: If the PCs wiped out the sclerid patch, use an intrusion here to have the patch regenerate. (If they refuse the intrusion, then the USPS mail carrier just rings the doorbell and delivers the package.)

PACKAGE: It contains a cypher (a weird helmet with wires, transformers, magnetic coils, and small parabolic dishes attached to it).

- Prop: Eschaton Electronics Package Label

- Mind Meld Cypher (Level 3): The Strange, pg. 322.

the violet spiral to force the Strange to read the wrong “memory location” and write Rukian reality into the prime world.) This would be specifically advantageous to the Karum because it would allow them to construct a backpack-size particle accelerator, which would be used, in turn, to “ping” the Strange energy network and provide a path for a planetovore to reach (and destroy) Earth.

the violet spiral to force the Strange to read the wrong “memory location” and write Rukian reality into the prime world.) This would be specifically advantageous to the Karum because it would allow them to construct a backpack-size particle accelerator, which would be used, in turn, to “ping” the Strange energy network and provide a path for a planetovore to reach (and destroy) Earth.

rushing past him. So let it happen.

rushing past him. So let it happen.