IN THE SHADOW OF THE SPIRE

In which unfortunate bargains are made in caverns deep beneath the city, and our intrepid heroes learn not to look a gift mobster in the mouth…

This session begins with the PCs waking up in chains after a disastrous battle.

There are several ways I could have handled this particular moment:

- I could have had all the characters wake up simultaneously.

- I could have arbitrarily chosen the order in which they would wake up.

- I could use some sort of mechanical resolution to determine how they would wake up.

- I could have had one of the character(s) get woken up by the bad guys.

- I could have the character(s) wake up by themselves.

Seems like a relatively simple crux — and I don’t want to suggest that I spent a lot of time staring at my navel on this one — but the ways in which you resolve moments like this can have a surprisingly large impact as the consequences of that moment ripple out.

First things first: I felt it was more interesting for the PCs wake up on their own. Why? Well, if they wake up on their own they have an opportunity to take actions (or choose not to take actions) which would no longer be available to them once the bad guys engaged with them. Conversely, anything interesting that might happen from the point where the bad guys wake them up would probably end up happening even if they did wake up first.

First things first: I felt it was more interesting for the PCs wake up on their own. Why? Well, if they wake up on their own they have an opportunity to take actions (or choose not to take actions) which would no longer be available to them once the bad guys engaged with them. Conversely, anything interesting that might happen from the point where the bad guys wake them up would probably end up happening even if they did wake up first.

When in doubt, go for the option with a larger number of potentially interesting outcomes. (Particularly if you’re not giving anything up to do it.)

Beyond that, I decided to turn to fictional cleromancy: I made a mechanical ruling and let it determine the order in which the PCs would wake up. (In this case, margin of success on a Listen check with a relatively low DC. As the characters woke up, they were then allowed to make Bluff checks to keep the bad guys from realizing they were awake.)

Couldn’t I — as the GM — have made a better decision myself?

Different, certainly. But better? Probably not. If I had arbitrarily decided for myself, I’d probably have chosen Tee to wake up first (since she would be the best positioned to stealthily slip her bonds). That would have potentially given a big, splashy scene. But when the cleromancy selected Dominic, the scene instead gave a quiet opportunity to spotlight a character who often just “went along with the group”. And although the choice to patiently wait and see what would happen might seem like a “non-choice”, it was actually very revealing of Dominic’s personal character (both to the table as a whole and, I think, to Dominic’s player).

Which is why I encourage GMs to trust the fictional cleromancy.

It’s important, of course, to properly set the stakes for any mechanical resolution and to make sure that you (and the rest of the table) will be satisfied with the possible outcomes. There’s no reason to let the mechanics drive you into a wall.

But, in my experience, games are much, much better when you set them free and see where they’ll take you. They’ll surprise and amaze you and create moments you never could have imagined happening in a thousand years.

You can see a couple other examples of this general sort of thing in the current campaign journal. First, resolving Agnarr’s Sense Motive check to notice that his friends had been brainwashed on a graduated scale led to his hilarious attempt to conspire with Elestra.

Second, in the back half of this session, Agnarr attempts to locate a stray dog to make his own… and abysmally fails his Animal Handling check. (Resulting in me describing him giving the dog iron rations, which the dog did not like at all.)

Why not just Default to Yes and let him have the dog? Gut instinct more than anything else. Getting the dog seemed important to the character, and I felt it would be more appreciated if it had to be worked for. It paid off: Failing to attract stray dogs became a running joke for several sessions, and when Agnarr finally did find his dog, the moment was more meaningful for the path that had been walked to get there.

All of this is an art, not a science.

LEARNING FROM FAILURE

Something else to note in this session, particularly in the wake of the near-TPK in the previous session, is how the group adjusted their tactics for underwater fights. Most notably, they made a point of making sure that they stuck together even when disparate results on Swim checks would have driven them apart. And you can see the payoff as they mopped up a whole sequence of combat encounters.

They learned from their mistakes and they learned from their failure.

There’s a branch of GMing philosophy which is basically terrified of the PCs failing at something. And I don’t just mean avoiding TPKs: They can never lose any fight. Every quest must be a success. No clue can ever be missed. No mystery can ever remain unsolved. No personal goal can be frustrated.

There are a couple of major problems with this philosophy.

First, you are eliminating a huge swath of the human experience (and drama!) from your games. Go watch a movie. Read a book. Reflect on how often the main characters are thwarted; suffer setbacks; get stymied. Look at how those failures are used to raise the stakes, drive the story forward, and frame new scenes — scenes that can’t exist if failure isn’t an option.

Second, when you never allow someone to make a mistake, they never learn that they’re doing something wrong.

If you spend any amount of time in RPG discussion groups, you’ll perennially come across GMs complaining that, for example, their players always rush headlong into every fight even when they’re clearly outnumbered and outgunned.

Do you ever let them lose those fights?

Of course not!

Well… I’ve spotted your problem.

Here the group had a problem with underwater combat. They suffered horrendous consequences. And then they fixed the problem.

This is a general theme you’ll see throughout these campaign journals: Not only characters (and their players) refining their strategic and tactical choices, but also figuring how to approach problems from new angles and with alternative solutions when their first options don’t work.

Failure is, in my experience, the root of creativity.

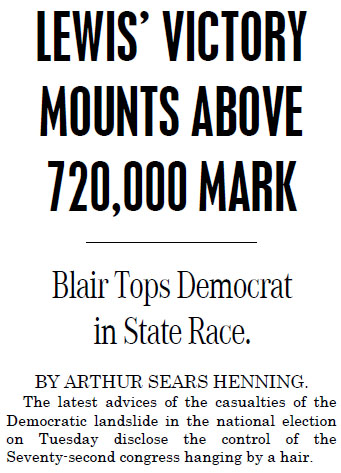

Note that a number of other papers used very similar designs, including the New-York Tribune and The Waco News-Tribune. So you can easily use these templates for articles from any number of sources (including fictional ones).

Note that a number of other papers used very similar designs, including the New-York Tribune and The Waco News-Tribune. So you can easily use these templates for articles from any number of sources (including fictional ones).