IN THE SHADOW OF THE SPIRE

IN THE SHADOW OF THE SPIRE

SESSION 26D: ELESTRA DIGS DEEP

August 24th, 2008

The 14th Day of Kadal in the 790th Year of the Seyrunian Dynasty

As two o’clock neared, Elestra headed to Tavern Row.

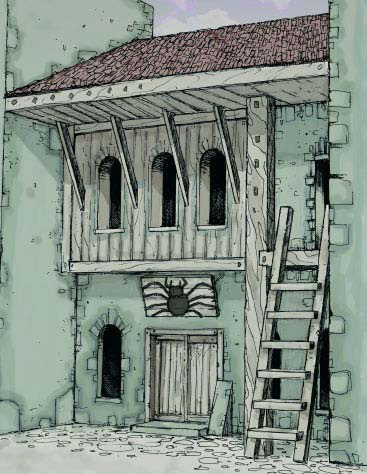

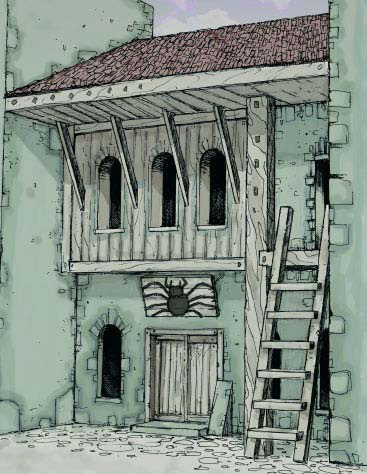

The Onyx Spider was a large, squat, two-story building wedged into the south end of Tavern Row. Elestra knew it to have a seedy and dangerous reputation. And as she passed through the front doors into the common room, it wasn’t hard to figure out where the tavern had gotten its name from: In the center of the room, levitating ten feet off the floor and embedded in a huge crystal sphere, was a giant spider carved from black onyx. It looked expensive.

Elestra spotted Jamill at the bar and pushed her way through the crowd to where he was standing.

“So you’re interested in the Brotherhood?” Jamill asked her, stonefaced.

Elestra nodded. “I might be interested in joining.”

“Might be?”

“I guess I just want to know about it.”

Jamill’s brow furrowed. “Right. Okay, who told you about the Brotherhood?”

Elestra hesitated. “A friend.”

“Who?”

“Well, it was more a friend of a friend… you know?”

“Who was it?”

“I don’t really… He kind of spoke to me in confidence and…”

Jamill slammed back the last of his amber-colored drink. “Okay, this is your last chance. Who sent you?”

Elestra suddenly became aware that two rather large men with short clubs strapped to their thighs had suddenly materialized out of the crowd behind her. She stammered, unable to find any kind of answer that would satisfy Jamill.

Jamill jerked his head and headed towards the back of the bar. The two thugs laid their hands on Elestra’s arms. She got the message and let them hustle her out through the back door of the tavern.

As they stepped through the door into the narrow alley behind the Onyx Spider, however, the two thugs briefly took their hands off Elestra. She immediately called upon the Spirit of the City and began her transformation in to a bird, hoping to fly away.

But the thugs were too quick for her. A large hand snapped out and grabbed the fragile sparrow-Elestra in mid-flight. She could feel it crushing the delicate bones of her new form and she was forced to abandon the attempt.

The two thugs reached for their clubs, but even as she landed lightly on the floor of the alley, Elestra was quick to draw her rapier. Her blade lashed out at the face of one of the thugs, cutting a deep gash through one cheek.

The thug screamed in pain, but even as Elestra grinned with satisfaction she felt the other thug’s club smash into her already aching ribs. Ignoring the blinding flash of pain, she spun around and cut a matching gash across the second thug’s cheek.

Jamill stepped out of the alley. He had drawn a longsword, but his swing seemed slow and clumsy to Elestra. She easily parried it and drove her own blade viciously past his defenses, skewering him through the stomach.

With a deep groan, Jamill let his longsword slip from his fingers and sank to the dirty cobbles of the alley. The two thugs stared at Elestra, glanced at each other, and then ran off in opposite directions.

Thinking quickly, Elestra grabbed Jamill (who had now slipped from shock into unconsciousness), threw him over her shoulder, and headed north towards the Ghostly Minstrel. Circumspectly circling around the inn, Elestra snuck in through the kitchen and headed upstairs.

She grabbed Agnarr from his room and left him to bind and blindfold Jamill in her room while she went back downstairs to leave a message with Tellith to let the others know that she would like them to come up to her room as soon as they returned.

TEE IS THE CLEVER ONE

Tee and Dominic arrived back at the Ghostly Minstrel together. Receiving Elestra’s message (by way of Tellith) they headed up to her room.

When they knocked, Elestra cracked the door slightly and peeked out at them. “Oh! Hello!” She visibly scanned the hall behind them to make sure that it was empty, then ushered them inside.

Agnarr was sitting on the bed with a vaguely bored expression on his face. Jamill was trussed up in the middle of the room, still unconscious. Elestra shuffled her feet nervously.

Tee looked back and forth between the three of them. “What am I looking at, exactly?”

Elestra, in a slightly disjointed fashion, explained everything that had happened. Tee was unbelieving. Wasn’t this exactly what she had told Elestra not to do?

“And then you brought him here?” Tee said, incredulously. “Why would you—“

Another knock came at the door. Tee quickly waved Elestra out of the way and cracked the door.

It was Tor.

“I had a message from Elestra to come up?”

Tee nodded. “Elestra has created a… situation.” She opened the door wide enough for Tor to see Jamill. “And it would probably be better if you weren’t part of this developing disaster.”

“Haven’t you just told him pretty much everything there is to tell?” Dominic said. “Just let him in.”

But Tor nodded to Tee and left. Tee shut the door.

“What—“ Elestra started.

“Shhh.” Tee cut her off. “Let me think.”

She had asked Elestra not to go asking questions, but she had. And now she was faced with almost exactly the type of situation she had feared: A cultist in their rooms, compromising whatever safety or security might be left at the Ghostly Minstrel. Anywhere else would have been—

“Elestra, I need you to go out and find a vacant warehouse. Somewhere far away from here. Try the South Market.”

“What are you—?”

“Just go. We’ve got to get this done before he wakes up.” Elestra left. Tee turned to Dominic and Agnarr. “You two stay here and keep an eye on him. If it looks like he’s going to wake up, knock him out again.”

Tee dashed out of the room and headed across Delver’s Square to Ebbert’s. She bought a strange, eclectic collection of material and then returned to the Ghostly Minstrel as quickly as she could.

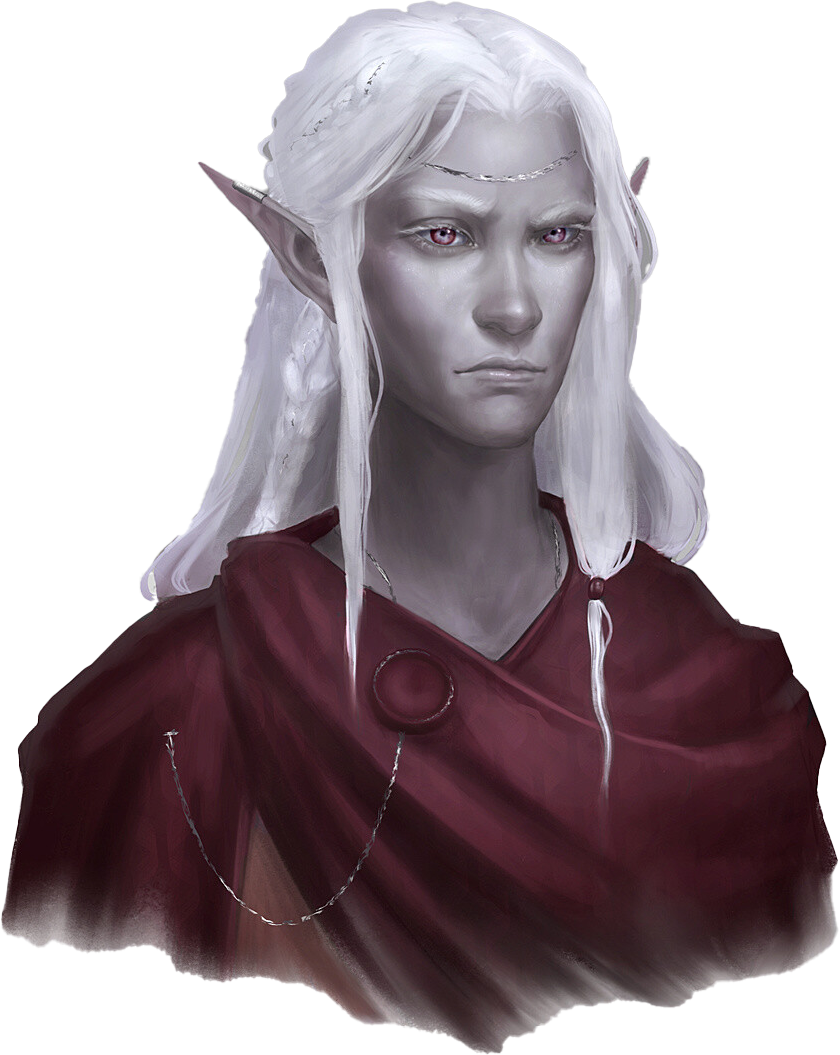

By the time Elestra returned with the location of a suitable warehouse in the South Market, Tee had stripped down the common items she had purchased and assembled the makeshift components of a primitive disguise. Her biggest goal had been to make herself look human instead of elfish, hoping that would be enough to throw people off the trail if it came to that. (Of course, Elestra hadn’t been disguised at all… but there wasn’t much she could do about that.)

Tee had Agnarr and the others carry Jamill downstairs and load him into a carriage, making protestations as he went about how his friend had had “too much to drink”. Tee surreptiously joined them a few moments later. She bribed the carriage driver well and had him drop them off at the empty warehouse.

TEE HUSTLES

There was a dilapidated chair in the corner of the warehouse. She had Agnarr tie Jamill to it and then told everyone to wait outside.

“Will you be okay?” Agnarr asked.

“If not, you’ll hear me shouting. I have big lungs.” Tee gave a slightly nervous grin.

Once the others had left, though, she slipped the broken square ring that they had found in Pythoness House onto her finger and pushed those nervous feelings deep inside and set her face in a look of cold determination. Then she slapped Jamill awake.

“I’m ashamed of you.”

Jamill shook his head. “What’s going on? Who are you?”

Tee removed his blindfold, carefully making sure that he would see the ring on her finger without letting him know that she was trying to make sure he saw it.

Jamill shook his head again, trying to get his bleary eyes to focus. “What happened?”

“You couldn’t handle a little girl?” Scorn dripped from Tee’s voice. “A little girl who turns into a bird?”

Jamill suddenly turned surly. “She was tougher than she looked…”

“She’s been dealt with,” Tee said with a finality that made it clear that Jamill was lucky that he hadn’t been “dealt with”, too. “You’re an embarrassment. You’re embarrassing us. Get out of town. Don’t come back.”

And then she left him… still tied up.

BACK TO ELESTRA’S ROOM

Tee rejoined the others. She stripped off her disguise and they returned to the Ghostly Minstrel, gathering Ranthir and Tor on their way back to Elestra’s room.

They quickly compared their notes from the day. Tor filled them in on his fear that Iltumar might be followed by cultists, his meeting with Shim, and the news that they had been followed.

“But Shim said that it was an Imperial priestess.”

“What does that mean?” Elestra said.

“Do you think that the Church might be in league with the cultists somehow?” Tee said.

Dominic suddenly looked queasy and uncertain.

“Or perhaps there are just some members of the Church who are cultists,” Ranthir said. “The Truth of the Hidden God said that the Brotherhood of the Blooded Knife infiltrates religions.”

“Is it possible that Rehobath is working with Wuntad?” Elestra asked.

A flurry of panicky hypotheses followed, but then Tor held up his hands. “There’s something else you should all know.” He paused for a moment, trying to find the right words to express something that felt like a confession. “I’ve started taking steps towards becoming a knight with the Order of the Dawn…”

“Congratulations!” Tee said, a huge smile spreading across her face. “That’s wonderful!”

“But that means,” Tor said, “That the priestess might have been following me. The Order might be keeping an eye on me to make sure that I don’t do anything unworthy.”

To a large degree, all of this left them back at square one: Tee hadn’t dared to ask Jamill any questions because it might have made him suspicious enough for her gambit to fail. They didn’t know how to interpret the information that Shim had given to Tor. All they’d really done was to confirm that Iltumar was tied up with some very dangerous people.

“As much as I hate to say it,” Tee said, “Elestra may have had the right idea. If we move quickly, I might be able to find someone else in the Brotherhood that I can talk to by using Jamill’s name as a contact… before he has a chance to warn them or they discover that he’s missing.”

This didn’t thrill any of them, but it seemed like their best chance at this point.

“Of course,” Tee said with a withering look in Elestra’s direction. “I’ll be taking proper precautions.”

And she walked out.

NEXT:

Running the Campaign: Counterintelligence Vectors – Campaign Journal: Session 27A

In the Shadow of the Spire: Index