Tagline: Best game of the year.

The opening paragraphs of this review launched a subtle salvo against what can only be described as the insanely bad reviews for UA which were getting posted to RPGNet at the time. These were reviews which, for example, were excoriating the game for not being as complex as GURPS. Or claiming that the game was completely unacceptable because its systems for magick were not practiced by real people in the real world. Seriously mind-numbingly bad reviewers.

Unsurprisingly, this salvo was not warmly welcomed by some.

I wish the original discussions had survived. They were… lively.

Reviewers should always keep in mind the creator’s goals.

Reviewers should always keep in mind the creator’s goals.

It doesn’t matter what you’re reviewing – whether its a novel, a play, a movie, or a roleplaying game – the first thing you should ask yourself is: What was the creator trying to create? The reason you ask yourself this is because it is as pointless to judge Independence Day as a serious attempt to comment on the burdens of the presidency as it would be to judge Hamlet as a children’s story. Often you will hear a negative review of something not because it failed to accomplish what it set out to do, but because the reviewer didn’t like what was being attempted. Such a review is useless. Because it attempts to judge the creation as something which it is not it is as useless as a review of poker which explains why the game fails terribly at being the Great American novel.

Figuring out what was being attempted isn’t always easy. Sometimes you’re forced to ask yourself whose creative impulses you should honor. For example, if you’re reviewing a production of a Shakespearean play should you judge it based on how well it accomplished the director’s goals or how well it accomplished Shakespeare’s? (Personally I feel the director’s goal should be to fulfill the playwright’s goals – otherwise he should be doing a different play; hence I would go with the latter.) At other times it is necessary to call into question the surface goal itself and dive beneath the surface – for example an artist might fully intend to create a giant pink phallic symbol in Times Square, but you have to ask whether or not this is a good idea based on the underlying goals of art and the function Times Square. Nor is it always easy to figure out what a particular person’s goals were in creating something. More often than not you must rely on intuition to ordain what was intended.

Sometimes, though, you get lucky. Something in the work will clearly state was being attempted. You know that GURPS was designed to be a generic, universal system not only from the title, but because the designers included a short explanation of what was being attempted and what they hoped the game would accomplish.

The reason I bring all of this up is because after taking a look at the varied extant reviews of Unknown Armies I think it is necessary to explain where this review is coming from. Knowing where Unknown Armies is coming from is easy: Greg Stolze and John Tynes tell you specifically what their design goals were in the conveniently titled section “Design Goals” on pages four and five. Despite this several reviewers have flown in the face of commonsense and judged intentional decisions as “mistakes” or “flaws”.

So, just to be perfectly clear: If you don’t like simple systems, you won’t like Unknown Armies. (“Pages and pages of rules for ballistics-based damage and a complete flowchart-governed sub-system for picking locks are just some of the realism-focused rules you won’t find in UA.”) The fact that there is a detailed tracking system for character personality in this game is intentional, not a mistake or an anachronism. (“If your character occasionally kills someone, it’ll be up to you to justify why this is okay – and if you can’t, the game’s rules will penalize your character by hardening him against the notion of murder.”) If you don’t like roleplaying settings which attempt to be completely original (I’m not kidding – I actually saw someone complain because the game setting was too creative), then Unknown Armies isn’t a game you want to be playing.

“It’s time to stop playing games.”

OVERVIEW

Atlas Games has become a pretty impressive company. The 1990s have seen the origination of a couple of trends in RPGs: One, the World of Darkness and the host of games which have been inspired by it. Two, the simple, cinematic rule systems packed full of action-potential (usually with an anime or John Woo/Jackie Chan/Hong Kong influence). Atlas Games now owns the two games which providing the lightning rod to these two trends (Ars Magica and Feng Shui), and with the production of Unknown Armies they may very well have created the game which provides the perfect merger between them.

Let’s cut to the chase: I love this game.

UA is, I’ll be the first to admit, possessed of some flaws – but it bubbles with such creativity, originality, potential, and brilliance that it overwhelms those flaws. There are games which fail because of their flaws; their are games which are tolerable in spite of their flaws; their are games which suffer slightly from their flaws; and then there are games where the flaws are beside the point. UA is the last of these.

More on this in a bit.

THE SETTING

Unknown Armies is the Illuminatus Trilogy.

This is an analogy which I have not seen broached before, but the tone of the Trilogy resonates throughout the game. I don’t mean that this is a setting inspired by the World of Darkness with elements of the Trilogy incorporated into it – for that game you should take a look at the disjointed Immortal. I mean that when you first enter the world of UA it feels very much the way it does when you first enter the world of the Trilogy: All the half-crazed conspiracies and crack-pot theories and urban legends you’ve ever heard are true at one level or another, but in a way completely alien to anything you might have expected. For the first hour you keep thinking you’ve got it figured out, only to have the rug ripped out from under you. Even by the time you’ve finished exploring the place you’ll still find things hidden in the corners that’ll make you doubletake (or run screaming in terror).

The basics concept is this: Magick is real and the world is a much more unnatural place than your common mortal ever imagines. The only people who know this are known as the “Occult Underground”, sharing only the common trait that they all know “the truth” (or at least parts of the truth).

The Big Truth is this: Karma and Reincarnation exist, but only at a universal level. When the world comes to an end it is reborn in a way consistent with its karma – we get the world which we deserve. The mechanism by which this takes place is the Invisible Clergy, who unite into the Godhead as the universe is reborn, guiding its creation. Humans “ascend” to the Clergy by fulfilling the role of an “archetype”. Each archetype represents some primal element of human society; these archetypes are not set in stone, but are rather mutable from one incarnation of the world to the next. To make things more interesting humans still on earth can follow in the footsteps of ascended archetypes, gaining powers through the association. Sometimes an archetype can be replaced, but that’s a story for another time. There are other big truths out there (such as the conflict between Entropy and Order which drives all of this), but that’s the barebones of what’s going on.

There are three other important elements: The Unnatural, the Unexplained, and Magick (technically you could consider Magick part of the Unnatural, but its important enough we’ll spin it off by itself). The Unnatural are those things caused by otherworldly forces. The Unexplained are things which, at first glance, may appear to be unnatural, but in truth have rational explanations (these are fun because they’re red herrings which keep you from being completely comfortable – you can’t just dismiss anything unknown as being mystical).

Magick is one of the areas where UA really shines. It is based on three Laws: Symbolic Tension, Transaction, and Obedience. Symbolic Tension means that all magick is “based on some form of paradox” – a central irony or contradiction. For example, entropomancy (where you have to injure yourself to create a magical effect) has a paradox in that to gain control (power) over the universe you have to surrender control over yourself.

The Law of Transaction is the magical equivalent of Newton’s third law: Magick doesn’t let you get something for nothing; what you get out is equal to what you put in.

The Law of Obedience means that no one can follow more than one magickal path. This makes logical sense in the game setting because magick is driven by your personal convictions about how the universe functions – being able to follow more than one magickal path would mean that you were simultaneously holding two incompatible convictions about how the universe functions. It’s like believing totally and completely in both creationism and evolution; it can’t be done (you can fake it – but faking magickal discipline gets you nothing but fake magick).

Those may seem familiar to you, but trust me when I say that magick in UA is about as unique as you can get. Each school of magick requires some form of sacrifice to build up a charge and then you can use these charges to cast magick. The schools themselves are the unique part though – pornomancy, for example, requires to engage in very specific sexual acts (but not to take pleasure in them); plutomancy requires you to earn money (but not spend it); etc.

(A brief side note: Some have raised complaints about the magick system because an adept (one who can practice magick) can attempt to do anything. It has been insinuated that this means that those with experience are no better than those who are newcomers. Anyone who has actually bothered to read the rules, though, would realize a couple of things: First, the game assumes anyone playing an adept is just that – adept in the use of magick; if you want to play someone who isn’t optional rules are provided. Second, those with a higher skill in magick are capable of succeeding at more difficult magickal tasks and doing more with them – saying that they are “both the same” is like saying that AD&D possesses no differentiation between 1st and 20th level wizards because they are both capable of casting damaging spells, despite the fact that 1st level mages cause 1d6 damage and 20th level mages cause 20d6.)

THE RULES

The basic rules for UA are dead simple. But unlike many other simple systems on the market they don’t require GM fudging to fill in the gaps – these are a solid set of rules. Here’s the breakdown of the page and a half of core game mechanics – the shortest chapter in the book.

1. Roll percentile dice.

2. A roll of 01 is an extremely great success.

3. A roll of 00 is a complete failure.

4. If result is equal to or less than your skill you succeed. The higher the role, the better the success. Some tasks will need a minimum roll to succeed (so, for example, you’d need to roll higher than 30, but under your skill).

5. If the result is less than your skill you fail.

6. Matched numbers are exceptional results – either extremely good if it was a success or extremely bad if you fail.

7. In some cases (such as you “obsession skill” – the skill you specialize in essentially) you can “flip-flop” a bad roll to make it good (turning a 91 to a 19, for example).

8. The GM may apply “shifts” to your roll – changing the number you rolled. (A -10% shift, for example, would turn a roll of 50 into a roll of 40.)

Combat, as usual, adds a few extras. Most importantly damage is handled by adding the two dice together from your skill roll (if you rolled a 43 and succeeded you would do 4+3=7 points of damage). Firearms are a special case in which your damage is equal to your skill roll within a certain range (so that if you succeeded with a 43 you would do 43 points of damage, unless the weapon’s maximum was 40 or its minimum was 50) – hence a shotgun can do a lot more damage than a .22, but not always.

Character creation embraces the same standard as the core rules – simple, but complete (with a noticeable exception, see the note below). It breaks down into the following steps:

1. General Brainstorming.

2. Personality.

3. Obsession: What your character is very good at – the skill which defines who your character is.

4. Passions: There are three passions – Fear, Rage, and Noble. You create your own passions, each passion causing the appropriate reaction in your character when it is encountered (unless, of course, you can give good reason otherwise). Hence your character might be frightened of spiders, enraged at the sight of a child in pain, and committed to saving the environment. In addition to being able to flip-flop your obsession skill, you can flip-flop any skill when it is being employed in regards to one of your passions.

5. Attributes: There are four attributes – Body, Speed, Mind, and Soul. You split up 220 points between them.

6. Skills: The skill system is almost entirely freeform (see note below). Essentially you can take as many points in Body skills as you assigned points to your Body stat.

7. Obsession Skill: Pick a skill which is related to your obsession and make it your obsession skill. If you want to practice magick your magick skill must be your obsession (because unless you are devoted to magick you won’t be able to make it work).

8. Cherries: Cherries are “special effects” which are attached to the matched double results of combat and magic skills. This has caused some complaints, but when you realize that violence and magick (the unnatural) are the focus of the game it makes sense that these are the skills which are given particular attention. Nothing stops you from assigning cherries to other skills, per se – especially since the cherries are designed in a freeform manner.

9. Your Wound Points equal your Body score.

(Another side note: Several reviews have taken exception to the fact that the skill system is almost completely freeform – a handful of “freebie” skills are detailed and a list of suggestions is given, but nothing is laid down in a concrete fashion. Some have claimed this to be a weakness, but actually it gives a huge amount of power to the player in terms of finely tuned control over their character. Since everything is veto-able by the GM it can’t have any drawbacks except that you actually have to think about and personalize your character. Even new players find this type of system easier, in my experience, then attempting to pick and choose from a list of skills they don’t fully understand. I wouldn’t want to try it with a detailed, complicated system; but for a simple system like this it’s the perfect fit. As for the whacko who complained about overlapping skills – what drugs are you on?)

There’s one other important mechanic to consider: The Madness Meter. The situations you encounter as a member of the Occult Underground are fully capable of driving your average person beyond the bounds of sanity. A character’s Madness Meter keeps track of five distinct areas – Violence, the Unnatural, Helplessness, Isolation, and Self. Each area has ten “hardened” slots and five “failure” slots attached to it. When a character encounters an abnormal situation (such as someone’s head being blown off in front of them or their first encounter with magic or being held captive or losing all your friends or being forced to take actions which you previously believed you would never be capable of) they make a check – if they succeed they become hardened to that type of event; if they fail they react either with “panic, paralysis, or frenzy” (at the player’s discretion) and gains a failure slot. The more hardened you become the more extreme situations have to be to cause a check, but the negative drawback is that you become less connected with the world (and this has a very real game impact). If you max out any of your failure bars you go psychopathic – which is not to be confuse with riproaring insanity or any such stereotype. This is a subtle and evocative game, not a slaughterfest.

I like the Madness Meter mechanic because it never forces a character action, it merely provides a guideline. Like the rest of the game it is simple, but powerful and effective at reinforcing its designers intents.

ANALYSIS

Every so often I come across a game which is so amazing that it makes me sit up and take notice of who was responsible for designing it. Jonathon Tweet for Ars Magica, Robin D. Laws for Feng Shui, the team of Dream Pod 9 for Heavy Gear — these are a few of the games and designers which immediately earned my respect and appreciation. They are the designers from whom I would pick up a new porduct simply on the basis of their name being on the cover.

With Unknown Armies Greg Stolze and John Tynes join that list. Not only the simple, powerful masterpiece which the engine of the game is. Nor for the rich and original world which they have created. No, what really raises this game to the next level is the immense expertise and masterful understanding of the foundations of roleplaying design which they demonstrate.

Stolze and Tynes are masters. I knew I had something in my hand which had been designed in brilliance when I read the Definitions of Roleplaying which are included in the introduction (one from each designer). Tynes’ definition — improvisational radio theater — particularly struck me. I had gotten the “improvisational theatre” part down, but the “radio” bit was the simple label which had escaped me for distinguishing between the table-top structure and the live action structure (and, sure, you might be able to say “that’s obvious”, but you didn’t say anything before, did you?). They then proceeded to confirm my impression by laying down in very precise terms what their design goals for the game were – something far more designers should take advantage of.

And it just didn’t stop. Throughout the entire product Stolze and Tynes expertly provided guidance without falling into the trap which Rein*Hagen did in designing Vampire — formalizing their suggestions and guidance into rules. When Stolze and Tynes provide a set of personality guidelines based on the signs of the zodiac they put them aside into an optional box – a convenient shorthand for NPCs, a potentially useful tool for new players. Rein*Hagen institutionalized it into a set of necessary labels.

Indeed the entire character creation system is an excellent example of this – by subtly encouraging character creation with killing the creative process through formalization — but this isn’t the only place it happens. The chapter on Campaign Creation, for example, does the same thing for the GM’s creative process – encouraging, guiding, but never “mandating”. The chapter on “Running the Game” is actually a useful summary of rules which are gathered together in one place along with concrete examples of how to handle common play situations, not a hodgepodge of questionably vague advice.

Finally the layout is great – with information clearly laid out an important information emphasized and isolated for easy reference during gameplay. Although the artwork is occasionally less than perfect it is expertly crafted and placed. The whole product is rounded out by what I consider to be the the most brilliant introductory scenario I’ve ever seen.

And all of this brings me, regrettably, to the weaknesses in UA: First, several key concepts lack an explanation. Specifically the concept of “synchronicity”, the astral plane, and the age of hermeticism are all mentioned in relation to other things several times in the text, but never given a description of their own.

Second, the flip-flop mechanic (discussed above) becomes less and less effective once a skill has gone beyond 50. This is odd for a mechanic which is meant to reflect a character’s intense devotion to a particular skill or cause.

Third, the index is lacking, although this ameliorated slightly by a detailed Table of Contents.

Finally, a set of very simple core rules is marred in a couple of places by unnecessary complication.

None of these weaknesses are particularly serious (especially if you’ve read the Illuminati Trilogy for the discussion of synchronicity, played any pseudo-mystical RPG including AD&D for the astral plane, or taken a gander at Ars Magica or the World of Darkness for the general feel of what the age of hermeticism must refer to) – even the flip-flop mechanic is little more than a slight annoyance which crops up only occasionally and is still generally intuitive.

CONCLUSION

Unknown Armies is the best game of the year. If all goes well it will be remembered as one of the best games ever. If you don’t put down the $25.00 for this treasure trove then you don’t deserve to call yourself a roleplayer.

‘Nuff said.

Style: 5

Substance: 5

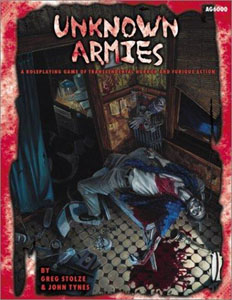

Title: Unknown Armies: A Roleplaying Game of Transcendental Horror and Furious Action

Writers: Greg Stolze and John Tynes

Publisher: Atlas Games

Price: $25.00

Page Count: 225

ISBN: 1-887801-70-7

Originally Posted: 1999/04/13

In retrospect, was Unknown Armies really the best game of 1999?

Yup.

As I mentioned in “UA-Style Rumours for D&D“, the fact that Unknown Armies didn’t catch on the way it deserved to remains one of the great mysteries of the roleplaying industry. But when you look at all of the other games which have pilfered its pockets in the last decade, its importance and its quality becomes very clear. If you’ve never seen it, then you should really, really take the time to check it out.

For an explanation of where these reviews came from and why you can no longer find them at RPGNet, click here.