Tagline: This is the stuff disappointment is made of.

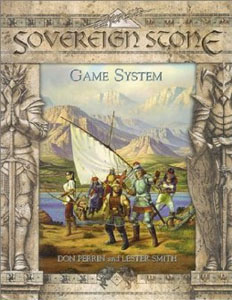

Some quick background: In July 1999, I wrote a review of the Sovereign Stone: Quickstart Rules. I thought it was fantastic and wrote the review specifically to highlight the game’s upcoming release. One month later, the game had been released; I had read it; and this review appeared. Then the drama started…

This is the stuff disappointment is made of.

This is the stuff disappointment is made of.

Let me start by saying that I’d like to issue an apology to anyone who bought this game based on my recommendation in a review of the Quickstart Rules a couple weeks back. Having obtained and read the core rulebook for Elmore’s Sovereign Stone I can now see that the potential I saw in the Quickstart Rules is completely unrealized. This is coupled with pathetic shortsightedness, poor conception, and an appalling sloppiness in execution.

INITIAL IMPRESSION

When I first saw Sovereign Stone on the store rack I was incredibly excited. I instantly recognized the elegant stonework framing an Elmore painting from the Quickstart Rules (although the painting is different). I picked it up and turned it over…

And began to get nervous. The back cover, in complete and utter contrast to the front, was black text on a plain white background (with a pale, blue pencil sketch design centered in the middle). You’ve probably seen books like this before – fronts and spines done in dark shades, and the back cover (for reasons beyond comprehension) done in an extremely light shade of an entirely different color. It screams “Amateur Land”.

No big worry, though. It wasn’t that bad. Right? Right. So I started flipping through it…

And my heart sunk. For reasons, once again beyond comprehension, the entire interior is printed in a grayish-brown ink – including the artwork. It was probably meant to set a mood. It succeeds brilliantly at being drab as hell. There were a few specific textual details which made things even worse, but we’ll cover those below.

So why do I own the book? Well, I was still hopeful. After all, the Quickstart Rules had really excited me. And it was Elmore, Weis, and Hickman, right? How could they go wrong?

All too easily.

A GROWING HORROR

Getting home I started reading it within the hour – I had been anticipating Sovereign Stone for quite some time, and I was anxious to get down to it. As I pushed farther and farther into the book, though, things got worse and worse.

Things started off well. The book begins with a table of contents and a two page map of the world, and then we move onto Chapter 1. Like Dream Pod 9’s Heavy Gear line of books, each chapter starts off with one page of flavor text – in this case a first person viewpoint of the world from each of the races (Chapter 1 is a dwarf; Chapter 2 is an ork; and so on).

It was when I hit the actual writing that I realized something was horribly wrong. First off, the writing style is stilted and amateurish – apparently aiming at a 4th grade reading level or lower most of the time.

Then we move onto the standard “What is a roleplaying game?” shtick. I don’t mind this, but the complete incompetence with which it is done is alarming — considering how many times its been done successfully, there are plenty of examples to draw from. For an example of the idiocy demonstrated here consider for a moment that the Sovereign Stone system uses the complete range of polyhedral dice. Not once – not here, nor anywhere else in the manual – is dice notation explained for the targeted neophyte.

This is also the section where we get the first inkling of a much larger problem. Here’s a little game for you. What header would you use to describe this paragraph:

The goal of the Sovereign Stone game is to give the players and the Game Master an interesting and exciting world in which to adventure, and an easy-to-play set of rules to enhance the adventure.

I’m willing to bet solid money that “Remember, This Is a Game!” was not the header you chose. I’ll bet it wasn’t even on the list. This is a persistent problem, with sections of text being labeled apparently at random.

And the lay-out problems don’t end there. The book simply isn’t constructed in a logical fashion. We jump from “What is Roleplaying?” straight to “Current Affairs in Loerem”. This doesn’t make any sense at all, I thought, we haven’t even been introduced to the world yet – none of this is going to make any sense. I was right.

Another little game for you: What’s the difference between “Nimra”, “Nimora”, and “Nimorea”?

Well, “Nimra” and “Nimora” are two of the eight kingdoms of the world of Loerem (where Sovereign Stone is set). Unless, of course, “Nimora” is actually supposed to be “Nimorea”. It appears as the latter on the map, the former in the text (sometimes), and its people are “Nimoreans”.

Where to begin? First off, having only one (or two) letter differences between two of your kingdoms is just plain stupid. It only leads to unnecessary confusion. Second, if you simply must do this thing, then there is absolutely no excuse for this shoddy excuse for copyediting.

A similar problem crops up when we get to languages: One of the languages is named “Karna”, spoken by Karnuans and Dunkargans. Which is fine, except for one thing: Karnu is a country which was formed after Dunkarga broke into two pieces in a civil war. So the language spoken mutually (and originating with the earlier people) is named after the latter group of people?

“Current Events” and “Languages”, however, are separated by the section on “Money” – which is pretty much like AD&D, except funny names have been given to all the coins and they’ve attempted to convince you that coins weighing the exact same amount but made in different times are worth radically different amounts (on an order of ten times as much for the older coins), but only for the silver ones.

One last generalized problem with the book as a whole, and then we’ll move onto Character Creation:

This is an RPG based on a world created by Larry Elmore, the famed fantasy artist, right? Larry Elmore is intimately involved in the production of the book, right? It is Elmore’s Sovereign Stone, right?

Right.

So can someone explain to me why this RPG is art poor in the extreme? Excluding the twenty-five pages of monsters (each of which has its own illustration), there are only forty illustrations in the entire book (a count which includes multiple instances of the same piece) – averaging only one piece of art every 3-4 pages. Many of these are small, and not helped in the least by the grayish-brown ink in which they are reproduced. Worst yet, they are almost all “people shots”. Between the skimpy text and the lack of illustrations, I have absolutely no idea what this world looks or feels like.

Not to mention the glaring inaccuracies. For example, we are told that the male clan dwarves “grow mustaches, though they do not grow beards”. Apparently someone forgot to inform Elmore of this tidbit (wait, isn’t it his world?) because every male dwarf depicted in the book (including the one accompanying the description of the clan dwarves) is shown with a beard. This type of error is repeated again and again and again.

CHARACTER CREATION

First off, the character sheet is reproduced twice – once on page 15 and once on page 16. Why? Apparently to balance the lay-out so that all of the two-page racial write-ups would be on facing pages.

Second, what do you think of this passage:

Additional Skills may be added to the character to make him more rounded. Refer to the Choose More Skills section to add Skills to your character.

How about this one?

A character possesses a pool of Life Points equal to his Vitality plus Willpower die maximums.

I hope you like ‘em a lot (plus about six others), because you’ll be reading them nine times.

This is because, after giving a two page write-up covering the general character creation process, the authors have then decided to include the basic character creation rules nine times – once in each of the racial write-ups (choosing a race is your first task). So you get a summary once, then you get it nine more times, and then you get the actual rules necessary for creating characters.

Allow me to express, as calmly as possible, my absolute fury about this: You could have produced these summaries and handful of actual rules (which take up almost an entire page) in the space you allotted to that extra, pointless character sheet. Then you could have used the space you saved nine times over there to give us more valuable information about each of the nine races (which, by the way, include five different nationalities of human) instead of the generalized cliches you have.

Why does this infuriate me? A brief digression is called for.

THE WORLD OF LOEREM, A BRIEF DIGRESSION

In my review of the Quickstart Rules I mentioned that one of the things I was really looking forward to was the potential in Sovereign Stone to do something really original and different with the standardized Tolkienesque fantasy tropes.

Well, it’s possible that the world of Loerem will live up to my every expectation. I won’t be one to know it, however. First, because I’m not buying anything else in this product line without a lot of evidence that things have improved. Second, because aside from a longish section giving one-page write-ups to all the monsters (ala Monstrous Manual), I’ve already discussed all the world information you get in the book. That’s right – a section on “Current Events”, the write-ups of the various races in the character creation chapter, a section on monsters, and that’s it.

Pathetic.

This is a 168 page book with more wasted space than a sub-lunar orbit. There is simply no excuse for the setting to not be covered in this volume.

BACK TO CHARACTER CREATION

Did you notice the number “nine” above? This makes sense, at first, because there are nine cultural groups shown on the map – Vinnengaelean, Nimra, Nimor(e)a, Dunkarga, Karnu, the Elves, the Clan Dwarves, the Unhorsed Dwarves, and the Orks. However, there are also the Trevenici – a nomadic race of humans spread throughout the world who don’t appear on the map.

Wait a minute, you say, doesn’t that equal ten? Why, yes. Yes it does.

So why are there only nine racial types you can select? Because this game sucks.

What’s missing? The Dunkargans. You know they’re supposed to be there, because the beginning of the Karnuan text reads: “The Kingdom of Karnu emerged as the victor in the debilitating civil war.” The civil war? What civil war? The civil war that would have been mentioned in the Dunkargan section, except that the Dunkargan section no longer exists.

What this means is that, somewhere along the line, the Dunkargan section got deleted from the text. And nobody noticed. Talk about half-assed. If it was done deliberately, then the Karnuan text should have been changed to reflect that. If it was done by accident, they’re just dumb as bricks.

I’m going to attempt to calm my rage long enough to explain the basics of the character creation system to you in a rational manner. It is essentially a seven step process (which, as noted before, is gone through more than nine times):

1. Generate Attributes

2. Calculate Life Points

3. Choose Traits

4. Choose Racial Skills

5. Choose More Skills

6. Starting Money & Gear

7. Name the Character

Generate Attributes. There are eight Attributes, which are measured by die types (so you might have a d4 in Strength and a d12 in Psyche). They are generated semi-randomly in two groups (four Physical Attributes and four Mental Attributes). First you roll 8d6, pairing the dice four groups of two. You then add those pairs together and consult a chart to determine the resultant die type (so pairing a 4 and a 2 would give you a score of 6, which, according to the chart, gives you a d6 die type). You assign each score to one of the four Physical Attributes. Repeat for the Mental Attributes. (The chart can be summarized as “if the score is equal to or less than the die type, while exceeding the previous die type, then it is that die type” – hence 2-4 results in a d4; 5-6 results in a d6; and so on.)

An alternate method is given, by which the GM gives each character 56 points to spread around the various attributes. If the GM wants a slightly more powerful campaign he can increase this number of points, “not to exceed 60” – a seasoned character would get 57; a veteran would get 58; and a hero character would get 60 (they don’t say what a character with 59 points would be called).

At first glance the system looks incredibly silly – a spread of four points? Wow! What flexibility! However, if you run the numbers through you’ll see that those four points can make a large difference – each additional point you give the characters essentially means they can get, in most circumstances, an additional attribute level. Since the system boils down, in the end, to five discrete levels (d4, d6, d8, d10, d12) those four levels mean a lot.

Calculate Life Points. The character’s pool of Life Points is equal to their Vitality die maximum plus their Willpower die maximum.

Choose Traits. Sovereign Stone uses a system of Advantages and Disadvantages. All Advantages and Disadvantages have a Minor level; several of them have a Major level as well (with slightly more serious consequences).

Each Race has a package of three advantages and disadvantages, except humans whose “package” consists of any advantage and any disadvantage. In the first step of choosing traits each character selects one advantage and one disadvantage from this package.

In the second step of choosing traits each character may then take an additional two Minor Advantages (or one Major Advantage), with a corresponding number of Disadvantages.

The system has three major drawbacks in my opinion: First, ad/disad systems are most useful for balancing out other parts of the character creation system. When they are allowed to do so, the ad/disad system helps break out the symmetry of character creation – attributes no longer have to line up along a bell curve, skills do not always total exactly the same number of skill points, and so on. As it stands, every part of Sovereign Stone is a perfectly balanced microcosm, which is generally inflexible.

But that’s mostly a personal taste (your mileage may vary, of course). The other two problems are far more serious. First, the racial packages encourage stereotypes and limit your options (particularly since you are forced to select one advantage and one disadvantage of them). Why must all elves be either honest, have a special enemy, or be possessed of a distinctive look? Why must all dwarves have a phobia, a special enemy, or battle lust? Why must orks either be infamous, indecisive, or greedy (i.e., they’re either a criminal, greedy, or wishy-washy)?

Second, there simply aren’t that many options. There are only eighteen advantages, three of which are variations of Animal Empathy, and one of which is limited to Orks only. There are only sixteen disadvantages (which balances with the advantages once you eliminate the Animal Empathy variations). Not only are clear opposites ignored (so you can, for example, negatively effect your wealth, but not positively effect it), but many options are left completely unexplored. “Lack of space”, as noted before, simply isn’t palatable in a book of this length – if something is left out it’s because you chose to leave it out. If you found yourself without inspiration crack open a GURPS book.

Choose Racial Skills. Each racial package has a short list of “racial skills” from which they must select four. All of the non-human races, except Unhorsed Dwarves, have one mandatory skill which they are required to select.

Choose More Skills. Total your attribute die levels to determine your initial Skill Points, which are spent progressively on buying die types in the skills you desire. This creates an interesting dynamic, in that you will almost certainly end up with more skill points than attribute points (since even with the semi-random system you’re going to choose pairs which result in the lowest possible total for the desired attribute). I don’t know whether this was intentional or not.

The only serious drawback here is that, for unknown reasons, no complete list of skills is provided for easy reference. You have to go wandering through the skill descriptions to find what you’re looking for.

Starting Money and Gear. To determine your starting money you roll Willpower + Dickering (or just Willpower if you didn’t take the Dickering skill) and multiply by four and add 80 – this gives you a total in silver coins. You then use this to purchase equipment (which is detailed in its own chapter).

One very nice part of the equipment system is the location system. The designers have taken the time to specify in what types of towns adventurers are likely to find each type of equipment – simplifying the GM’s job and discouraging the common practice of beginners to have every village shopkeeper possessing every item in known creation.

Name the Character. This is actually handled quite well. Each racial type is given a couple of paragraphs in which their naming conventions are briefly discussed.

Overall, the character creation is solid. I would have liked to see non-random options introduced for all the default randomness, but that’s no big deal.

However, character creation, like everything else in this book, suffers greatly not because of what it is, but because of how it was presented. The system itself is admirable, but it is presented in a way which is repetitious and under-detailed. Did I need to read the same text several times over? And if you could afford the space to do that, why are there other things which you don’t give enough of?

RESOLUTION MECHANIC

The basic resolution mechanic is simple: Roll your applicable Attribute die type and your applicable Skill die type, add them together, and compare to an assigned Difficulty number. Unskilled actions are resolved by rolling only an attribute die. An opposed action is successful for whoever has the higher die total.

In addition, you can choose to “exert” on any particular action – by taking stun damage (representative of the amount of exhausting yourself by over-exerting) you can add an additional die to your resolution. The more stun damage you take, the higher the die type you can use. (Wait a minute, you say, stun damage? I thought damage in the system was handled through a Life Point pool? Yup. If you’re confused by this review, you’d be no less confused by Sovereign Stone which routinely pulls this “using the rules before explaining them” routine. Sometimes there’s no way to avoid this, but at the very least reference should be made.)

COMBAT

Speaking of damage, let’s take a look at the combat system.

As I mentioned in my review of the Quickstart Rules, it was here that I started getting excited about Sovereign Stone. The rules were clean, being a nice, clear extension of the basic mechanic. They felt very much to me alike an “AD&D done right”.

This hasn’t changed… mostly. There’s a couple of places where the rules have been altered from the Quickstart Rules. Usually for the worse. I’ll discuss this as it comes up.

First, the designers seem to have found a nice compromise between the easy bookkeeping of traditional Hit Points and the slight edge in verisimilitude of Wound systems. Your character has a pool of Life Points (which is shown as a strip of boxes on the character sheet) and can take two types of damage: Stun and Wound. If you take Stun damage you mark off from top down; if you take Wound damage you mark off from the bottom up (with Wounds superseding Stun if the two meet). If all of your Life Point boxes are marked off you fall unconscious. If all your Life Point boxes are marked off as wounds you die. Nice and simple.

[ That’s the way it’s described in the rulebook. If you want a more mathematical, rather than visual, approach to this record-keeping: You have a pool of Life Points. You can take Stun Damage and you can take Wound Damage. If your Stun Damage + Wound Damage total is higher than your Life Point pool you fall unconscious. If your Wound Damage total is higher than your Life Point pool you die. ]

Battles are divided into turns (lasting approximately six seconds) in which each character gets to take one action (which is declared at the beginning of the turn). Before anything is resolved everyone rolls the dice for their declared action (this is important) – the highest resulting roll goes first, the second highest next, and so on down to the lowest roll.

Now, if you are attacked before taking your action for that turn you have two options: You can attempt to defend or you can “tough it out”. If you decide to defend you roll your dice again. If your new total is higher than the attacker’s then the attack is unsuccessful. If it is lower then the attack is successful and damage is determined by Attacker’s Total – Defender’s Total + Weapon Damage Bonus – Armor; which is then divided evenly between Stun and Wound damage (round in favor of stun) unless the bonus states otherwise.

“Tough it out” replaces “take the attack” from the Quickstart Rules. With “take the attack” you weren’t actively defending, but would still attempt to dodge the blow, rolling your Agility Attribute only. Damage was determined the same way. “Tough it out” is handled exactly the same way, except that when you take damage it raises the Difficulty of whatever action you are attempting to take.

This change was badly thought out. The version found in the Quickstart Rules provided a nice dynamic. Before showing you how that dynamic has been ruined, let me explain one last catch: If you’ve already taken your attack (i.e., you went first in the turn) and someone attacks you, then you can actively defend without losing your attack for that turn.

Example. Using the Quickstart Rules you and a taan both want to beat on each other with swords for awhile. You both declare your intention (“I wanna beat up on the other guy”) and then roll your initial dice (Strength Attribute + Sword Skill). You get 14 and the taan gets 11, therefore you get to go first (since you have the higher total). The taan decides to take the attack, so he rolls his Agility Attribute and gets a 7. You subtract 7 from 14, add your sword’s damage bonus (let’s say it’s 3). The total damage would therefore be 10, making for five points of Stun damage and five points of Wound damage (evenly divided).

Because the taan took the attack, the taan now gets to attack back – using his original total of 11 (because this was his declared action). You still get to defend, because you went first – roll your Strength Attribute + Sword Skill and get 12. Because your total was higher than his, his attack is unsuccessful.

Under the new system, however, the taan has his difficulty raised by the damage which was inflicted. So let’s take a slightly different look at this example:

Example 2. Because the taan took the attack, the taan now gets to attack back – using his original total of 11. You still defend, but let’s postulate that you got a Strength Attribute + Sword Skill total of 10 this time. Under the Quickstart Rules you would have been unsuccessful and the taan would have hit you, but under the new rules you defend just fine – because the taan gets a -10 modifier and his effective total is reduced to 1.

Do you see what happens? Before you could decide to make yourself easier to hit in order to still get off an attack, but under the new system you make yourself easier to hit and the fact that you get hit means you are unlikely to have a successful attack (especially since the other guy still gets to defend). “Tough it out” ceases to be tactically useful.

I say all this, but let me now modify it by saying that I have no idea if what I just told you is correct. Why? Because the rules are presented in a muddy, incompetent manner. First, in the Quickstart Rules it is laid out quite plainly that if you attack first you can still defend against later attacks. In this rulebook, however, that is not plainly stated – although it is stated that a defensive action cancels your declared action. So it’s possible that this entire dynamic has simply been removed, which is even worse. (Plus, how does it all interact with the new mechanic which states that each additional defense costs a point a Stun? Does that apply to defenses taken after a declared action? And if you can’t defend if you’ve already taken your declared action, why not?)

Second, the rules state: “Of course, any Wound damage suffered in this attack will still modify the dice roll for the target’s declared action, changing the order of his action as well as affecting its success.” This is odd. “Of course”? “Still”? This rule is not mentioned anywhere else in the text. Is it an artifact from an earlier edition of the rules? If I ignore it the rules certainly improve. Does this apply to other attack situations or not? If I fail to defend against your attack, does the penalty apply to all future defense actions I take in that turn?

The rules are simply put together badly and explained worse. They’ve ruined what was presented as an elegant, simple system in the Quickstart Rules.

They make things even worse. In my review of the Quickstart Rules I mentioned specifically how happy I was that they had trimmed away the “needless and contradictory fat” of the AD&D combat system. I spoke too hastily. The fat is back with avengeance – special modifiers plague the system throughout, along with reference charts and special case options.

Another odd thing: The rules for determining what happens when two characters tie for initiative have mysteriously disappeared. In the Quickstart Rules the decision of defense type was left in the hands of the PC. Given that the decision is no longer palatable (you can either not attack at all or have a good chance of giving an ineffective attack) it is unsurprising that some other compromise should be found. Unfortunately, this compromise is never detailed.

MAGIC

I mentioned in my review of the Quickstart Rules that I thought they had a solid foundation laid down for their magic system – with a couple of additions and extrapolations (magical item creation, for example), they could easily be a contender for one of the best magic systems in the biz.

Well, the solid foundation remains. And that’s it. None of the extra material or extrapolation which should be present in a full-sized game are present here.

Basically it works like this: Magical spells have difficulty numbers. He rolls his Psyche Attribute + Magic Skill and totals the dice – if the total is higher than the difficulty number he succeeds immediately; if not he may try again on the next turn, adding the new total to the old total until he gets a total higher than the difficulty number. The more complex the spell the higher the difficulty number, the higher the difficulty number the more turns it will take before the mage is successful.

Unlike combat they haven’t weighed the system down with inconsistency, gaping holes, or needless complication. Across the board the system is clean and nicely handled.

The cosmology behind spell-casting is relatively simple: Each race is advantaged in one of the four elements (earth, fire, water, air). It is easier for a spellcaster to learn spells dealing with the element which his race is advantaged in, and more difficult in spells opposed or unrelated to his advantaged element. In addition there is a fifth element, the Void, which is opposed to all of the elements – but which any spellcaster can pick up. (There’s some nice “Taint of the Void” mechanics which I won’t take the time to get into here.)

SYSTEM SUMMARY

If there’s any reason to pick up Sovereign Stone at all it would be to cannibalize and fix-up the system, which is excellent. Basic Resolution, Combat, and Magic are all clean, simple systems which get the job done in an elegant and easy-to-learn manner. Even Character Creation is decent, although it needs the most work.

The only problem the system information has is that it is presented in such a shoddy manner. Besides the general problems discussed above, you end up with idiocies such as describing what attributes are at the beginning of the “Basic Rules” chapter – despite the fact that this chapter comes after the “Character Creation” chapter and therefore there is no need to explain what attributes are (particularly since you discussed them about a dozen times). (If I had to guess, I would say that they were initially going for a White Wolf-style lay-out where the basic rules would be explained before character creation. When they changed their mind they simply cut-‘n-pasted the section without thinking to rewrite it.) This problem is not the exception to the rule (if you’ll pardon the pun), but representative of a generalized fault.

THE WORLD OF LOEREM

Essentially the world of Loerem suffers from three things in this book: First, a lack of information (discussed above to some degree). Second, they try too hard at times to distinguish the world from other Tolkienesque worlds. And, third, they don’t try hard enough to distinguish the world. Here’s what we know of the world:

General History. A long time ago the Kingdom of Vinnengael ruled the continent under a golden age. Actually, I’m not sure it was that long ago – since no dates are given and one of the quoted human characters specifically references this earlier time period as if he had lived in it (I’m willing to chalk the latter up to one more instance of sloppy writing, though). At that time the Gods blessed certain humans with holy power. These humans became known as the Dominion Lords. The King of Vinnengael requested that he be given the power to make Dominion Lords for the other races, and he was given the Sovereign Stone in order to make that happen. At some point the Sovereign Stone was broken.

General Current Events. Dagnarus, Lord of the Void, was thought killed long ago (in circumstances so mysterious they’ve decided not to tell us about them), but he wasn’t (whoa!). He’s actually some form of undead and he craves the Sovereign Stone (for reasons so mysterious they’ve decided not to tell us about them). He has returned to this world with a massive army of Taan (“fierce creatures from another part of the world”… so mysterious that they’ve decided not to tell us where), led by his undead knights known as the Vrykyl.

Humans. There are five human kingdoms: Vinnengael, Dunkarga, Karnu, Nimra, and Nimor(e)a. Vinnengael is an empire which is in steep decline (they don’t even mind that they’re being invaded); Karnu split off from Dunkarga in a civil war which was comparatively recent (but at a time so conspicuously recent that they’ve decided not to give us any dates… oh wait, I don’t even know what the current year is), but not so recent that Karnuans don’t have an entirely different culture than Dunkarga; Nimor(e)a is a northern settlement of the Nimran people (settled so long ago that they’ve decided not to… oh nevermind). Vinnengael is the decadent one; Dunkarga is the timid one; Karnu is the aggressive one; Nimrans are the traders; Nimoreans are the hardy barbarians living in a harsh land.

Not Enough Information: Almost everything we are told about the human cultures is ancient – mainly how their modern borders and politics were defined by the Fall of Old Vinnengael.

Trying Too Hard: “And here’s a completely different culture….” Historically you end up with a lot of different nations, all very similar to one another, grouped together. You get “Asian Countries” and “European Countries” and “African Countries” – you don’t get “An Asian Country” and “A European Country” and “An African Country”.

Not Trying Hard Enough: You have probably already noticed that all these cultures can be broken down into traditional fantasy roles. There is, of course, a great deal of variation which could be done within any one of these roles – but we simply aren’t given enough information about any of them. As a result, everything defaults to a cliché.

Elves. Elves are the Asians of the setting (cunningly located to the north to throw you off the scent). They have elaborate customs, an ornate system social order, and so on.

Not Enough Information: Every elf in the book is shown with a face paint or tatooed design around their eyes. What does this design indicate? I dunno. It’s never explained.

Trying Too Hard: Elves don’t like magic. Why? Because elves do like magic in any other Tolkienesque fantasy setting.

Not Trying Hard Enough: Well, they have an elaborate set of customs. And they are…? They have an ornate social order. And it is…? Once again, we are given cliches where hard information would have been preferred.

Dwarves. Dwarves are Mongols who believe they will inherit the planet someday. They are members of large clans which travel through the eastern steppes on their horses. However, some dwarves are cast out of this clan and become known as the Unhorsed.

Not Enough Information: Nothing specific, although the dwarves are as poorly described as everything else in the book.

Trying Too Hard: Dwarves like magic. Why? Because dwarves don’t like magic in any other Tolkienesque fantasy setting.

Not Trying Hard Enough: You’ve heard this complaint before. We’re given the cliché, but nothing to back it up with.

Orks. Orks are largely a seafaring race, with a complex social system based on this fact and their life as traders.

Not Enough Information: Orks believe themselves to be the first race on Loerem, tracing their ancestry back to the sea monsters known as “orca”, from which they derive their name. Why aren’t the “orca” described in the book? Are they supposed to be whales, as their name might indicate?

Trying Too Hard: Actually I don’t have any problems here. The Orks have been differentiated to a large degree from your standard orcish fare, but they have been done so in an intelligent manner across the board.

Not Trying Hard Enough: Once more, Sovereign Stone proves itself to be King of the Cliché.

You might be thinking to yourself: “Wow, nice summary.” Afraid not. If you buy this book you won’t be getting much more information than I’ve imparted to you here. Personally I still think Loerem has a lot of potential, but it remains no more realized here than it was in the Quickstart Rules. Indeed, it is worse. With the Quickstart Rules you were given practically nothing in the way of world background – which was acceptable, since what was hinted at was promising. Here, however, you are given just enough so that everything strikes you as clichéd and nothing strikes you as original.

Very disappointing.

OTHER STUFF TO HATE

If you’ve read my review of the Quickstart Rules you probably remember me mentioning the foolishness of describing your magical Portals in terms which in no way distinguish them from the Waygates of Robert Jordan’s Wheel of Time. Let me say here and now that despite my complaints of the method used in the Quickstart Rules, that method is vastly superior to the method selected for this core rulebook.

To whit: The Portals aren’t discussed anywhere in this book. They are mentioned many times (and apparently there’s a major military action involving one of them, but it’s very vague), but never explained. This is symptomatic of the entire game – things simply are not discussed when they should be.

Did I mention that they don’t appear in the Index, either? They share this trait with many other things, and the things which are mentioned usually aren’t comprehensively referenced. The index is a piece of crap.

To give you a total understanding of just how shoddy this thing is, let me draw your attention to something else: The game is called Sovereign Stone. Why? Because there is a major artifact of some sort known as the Sovereign Stone. It’s of fairly significant importance even beyond the implications of its titular role – it leads to the fall of Old Vinnengael, the separation of Nimra from Nimor(e)a, Dagnarus’ invasion, and is what allows for the creation of the Dominion Lords. What is it, though?

How the hell should I know? Although it is mentioned a couple of times it is not discussed in any detail. This is like the core Dragonlance manual not discussing the dragonlances.

WRAPPING THINGS UP

Why am I so furious? Why is this review filled with invective I have never before unleashed?

Because this game is so damn disappointing.

Sovereign Stone is a travesty. It has a world brimming with potential. It has a rock solid set of rules. It has a creative team with a proven track record any other start-up in this industry would die for.

And it sucks.

Unreservedly. Without qualification. With utter conviction. Sovereign Stone sucks. It is a waste of paper. It is in serious competition for the worst roleplaying game I have ever owned. The World of Synnibar was done better.

I wish I could say, “Go out and buy this game. If nothing else, it’s got some great ideas.”

In all good conscience I can’t say that. There are some good ideas in there, but they are not only presented in an ugly, debilitating fashion – their potential is completely unrealized and is hidden away at every possible opportunity.

Sovereign Stone is not worth your money or your time. Stay as far away from it as you can.

Style: 1

Substance: 1

Author: Don Perrin and Lester Smith (Larry Elmore)

Company/Publisher: Corsair Publishing, LLC and Sovereign Press, Inc.

Cost: $25.00

Page Count: 168

ISBN: 0-9658422-3-1

Originally Posted: 1999/08/16

This review caused an uproar. First, there were the people who were incredulous that my opinion of the Quickstart Rules and the core rulebook could be so diametrically opposed. Second, there were the authors and publishers who were absolutely furious. Third, there were the people who had also bought the rulebook and were generally confirming every negative thing I had to say about the game.

The publishers would later admit that they had sent the wrong file to the printers: Instead of the final draft of the book, they sent a much earlier draft that had not been fully proofread.

Which explained some of the horrible editorial problems the book had and possibly even some of the design issues, but didn’t explain the massively underdeveloped (to the point of being unusable) setting.

One incident that stands out in particular for me happened at Gencon: Despite the crushing disappointment of the core rulebook, my interest in Sovereign Stone had not abated. So I stopped by the Corsair Publishing booth and was looking over the product line. Someone associated with the company came over and started chatting with me. Then I very distinctly remember them looking down at my name badge, reading my name, and then looking up into my face. “Oh,” they said. And then turned and walked away.

So I put the book back down and walked away.

For years now, I had placed this memory at Gencon 1999: That I had written the review, there had been an uproar, and then I had gone to Gencon and in the heat of that uproar the fellow from Corsair had simply wanted nothing to do with me.

But in prepping this review for reposting here at the Alexandrian, I’ve realized that this timeline doesn’t work: My review didn’t appear at RPGNet until a couple weeks after the convention. So the incident in the Corsair booth actually happened at Gencon 2000. This actually makes sense, because this definitely happened at the same convention that Orkworld was released at (which I remember because of the “feud” John Wick and I supposedly had going on, which neither John Wick or I actually considered a feud… but that’s a story for another time), and Orkworld was definitely released in 2000.

Memory is a tricky thing. On the other hand, that actually makes it a sadder story. I was in the booth because I was genuinely interested in seeing how the Sovereign Stone product line had developed, but the fellow from Corsair apparently thought I was there to do some sort of “hit” on their new books. As a result, I’ve never actually picked up another book related to Sovereign Stone and they didn’t get the positive reviews I might have written (assuming the books had actually improved, of course).

C’est la vie.

For an explanation of where these reviews came from and why you can no longer find them at RPGNet, click here.

Cheapass Games has created quite a reputation for itself. Producing games from the cheapest materials possible, they create highly affordable games with highly original premises. Almost all of their games have catchy titles and/or taglines, and their concepts are usually intriguing and amusing enough in their own right so that, even if the gameplay doesn’t catch your fancy, the product is still well worth the cost of entry.

Cheapass Games has created quite a reputation for itself. Producing games from the cheapest materials possible, they create highly affordable games with highly original premises. Almost all of their games have catchy titles and/or taglines, and their concepts are usually intriguing and amusing enough in their own right so that, even if the gameplay doesn’t catch your fancy, the product is still well worth the cost of entry.