Lately I’ve been reflecting on the “nostalgia kids” subgenre of urban fantasy / supernatural horror. It’s epitomized by Stephen King’s It and Hearts in Atlantis, J.J. Abrams’ Super 8, and, of course, the recent sensation of Stranger Things. There are a lot of different elements which make this subgenre work, most of them shared by supernatural coming of age stories in general (e.g., E.T.) — the innocence of the protagonists; their vulnerability and isolation; the supernatural elements as metaphors for both the unseen aspects of a child’s life and also the “secret lore” of the adolescent passage to adulthood; and so forth.

But I think the aspect of the “nostalgia kids” stories which makes them unique and distinct is the contrast between the nostalgia-tinged view of the past and the supernatural abnormality. Most supernatural horror movies, of course, feature a rupturing of our expectations of the real world. But the nostalgic milieu heightens the sense of “rightness” and, thus, the fundamental wrongness of the supernatural element which disrupts our image of a well-remembered yesterday.

Well-told versions of these stories operate even when the reader/viewer is not personally nostalgic for the era in question, because the narrative conveys the nostalgia itself. (This is the case for me with, say, Back to the Future and It, which are soaked in nostalgia for an era I did not personally experience. Conversely, Stranger Things and Ready Player One both conjure forth eras I personally experienced, albeit in very different ways.)

You can see this same fundamental tension between nostalgia and the disruption of memory in the artwork of Simon Stålenhag:

Stålenhag conjures forth a nostaglic image of the ’80s and then disrupts that nostalgia through the presence of giant robots, rusting remnants of colossal technology, and levitating vehicles. You can see how the fantastical elements of these images are heightened by the context of the nostalgic imagery:

If you simply took the image of this giant mecha, for example, it would be pretty cool. But placing it the context of the ’80s police cars lends it a very specific and particular resonance.

RECURSION ERROR

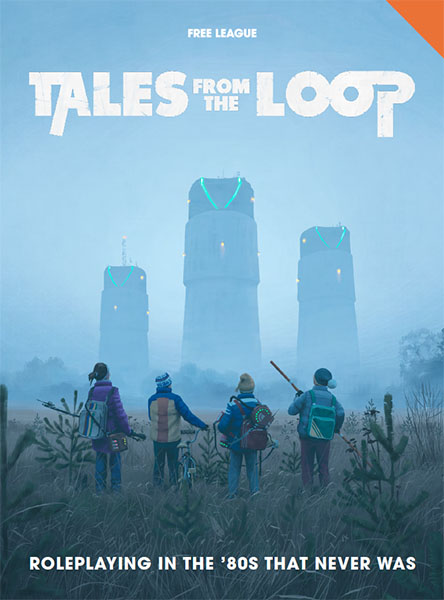

So at some point the designers of the Tales from the Loop thought it would be cool to set a roleplaying game in the world created by Stålenhag’s art.

But there’s a problem. When you take elements of Stålenhag’s art, use them to construct an alternative history of the ’80s, and then say, “this is the world your PCs think of as normal, but there will ALSO be these other elements which are totally weird and supernatural and stuff” you end up with a recursion error: The game wants you to evoke nostalgia and then disrupt it with the fantastic in order to create a very specific mood and emotional response… but then tells you to NOT feel that mood or have that emotion in response to these OTHER fantastical elements. The fundamental dynamic of the “nostalgia kids” genre is disrupted because the game is constantly undercutting the thing which the game is supposedly about.

But there’s a problem. When you take elements of Stålenhag’s art, use them to construct an alternative history of the ’80s, and then say, “this is the world your PCs think of as normal, but there will ALSO be these other elements which are totally weird and supernatural and stuff” you end up with a recursion error: The game wants you to evoke nostalgia and then disrupt it with the fantastic in order to create a very specific mood and emotional response… but then tells you to NOT feel that mood or have that emotion in response to these OTHER fantastical elements. The fundamental dynamic of the “nostalgia kids” genre is disrupted because the game is constantly undercutting the thing which the game is supposedly about.

In actual play, we found that this tended to result in Stålenhag’s elements being minimized or even eliminated during play. But isn’t the entire point of the game to be an RPG about Stålenhag’s art? (I think they might have been better served making a game about those police cars: Embrace the alternate history and make a game about law enforcement needing to deal with the complexities of mecha and robots and hovercraft in the ’80s. But I digress.)

CHARACTERS ARE COOL

What works great, on the other hand, is the character creation system. It generates really rich PCs with very game-able home lives in a surprisingly small amount of time: It is absolutely possible to sit down with a group, walk them through character creation, and have a meaty and significant first session of play all in a single evening.

At the end of character creation, your Kid will be fleshed out with a drive, anchor, problem, pride, favorite song, and significant relationships. And what makes this really work is that the mechanics make these elements immediately meaningful through gameplay. For example, the action of play will generally leave your Kid afflicted with Conditions (like Upset, Scared, Exhausted, and Injured). The only way to deal with these Conditions (before they pile up and overwhelm you) is to either have a meaningful scene of interaction with the other kids (which helps a little) OR to have a meaningful scene of interaction with the adults in your life.

This constant “touching base” with the home life of the character is really essential for the game to sing (and something we’ll be coming back to in a second).

SYSTEM IS BROKEN

Unfortunately, the biggest problem with Tales from the Loop is that the system is broken. Not quite in a “this is terrible and unplayable” way but in a “this is really making for a mediocre experience” kind of way. (It’s like driving a car with a shattered windscreen: The car technically performs its function, but it’s not exactly ideal.)

The key problem is that the success rate for the core mechanic is abysmal. You Kids will generally have about a 40-50% chance of succeeding at a test, and that’s before you get hitched into the death spiral that’s the typical result of failure. (Failure generally applies a Condition; Conditions drastically reduce your chance of success.) It creates an incredibly frustrating experience. And maybe that’s intentional (you’re playing Kids), but it becomes really problematic in a game designed entirely around mystery scenarios with skill tests as the gateways for navigating those mysteries.

As an experienced GM I had a number of ways of routing around these problems, but watching a relatively new GM ram her face into the mechanics and having her scenarios grind to a painful halt over and over again was unpleasant. (And even rerouting around them is, obviously, a needlessly frustrating experience.)

The system is also kind of curiously random in the narrative control it gives to the players. For example, the game features the “description on demand” technique in which the GM randomly asks a player to fill in the details of the world (because, hey, that’s like having narrative control, right?). And it mechanically does stuff like giving players the ability to create NPCs out of whole cloth with whatever skill set and background they want without the GM being able to say anything about it. But then it runs in abject TERROR at the idea of letting players decide what NPCs can be reasonably convinced of and strenuously emphasizes that the GM can veto it.

It also contrasts even more oddly with the book’s raging hard on for railroading. A frequent refrain is, “Are your players not interested in something? Remind them of their Drives AND TELL THEM TO GET WITH THE FUCKING PROGRAM.” (I might have made the subtext into text there.)

UNSTATED ASSUMPTIONS

Contributing to the systemic problems of Tales from the Loop is that the designers seem influenced by games like Apocalypse World, but don’t seem to fully understand what makes Powered by the Apocalypse games tick: They’ve got Principles and a discussion of how mystery scenarios can be constructed… but don’t seem to grok that the reason these things work in PbtA is because they’re mechanically supported RULES. After a great deal of experimentation, I’ve concluded that the game works best if you follow three “best practices” (which are, unfortunately, not clearly called out in the text):

First: Fail Forward Resolution. This makes the abysmal success rates less painful, and the game does include the Conditions mechanic which can be used as a default consequence: You’ll still achieve your goals, but you’re going to pay for it with a physical or emotional condition which you need to deal with.

Second: Narrative Resolution. Partly because this approach lends itself towards fewer checks resolving larger chunks of narrative (which reduces the number of tests and makes the whiff rate of the core mechanic less painful).

Third: Treat the suggested mystery structure as LAW. Most notably, make sure you are consistently alternating between Mystery Scenes and Everyday Life Scenes. When confronted with a mystery scenario, many gamers will dive in and not come up for air until the scenario is resolved. Although, somewhat incoherently, several of the scenarios in the book don’t lend themselves to this style of play, the Conditions mechanics will push you in this direction naturally and we consistently found it was essential to get anything remotely playable out of the system.

CORE SCENARIOS

Speaking of scenarios, I should note that the core rulebook for Tales from the Loop is chock full of scenario material. (It actually takes up a majority of the 196 page book.) This includes four traditional scenarios and a “Mystery Sandbox”.

The latter is interesting because it’s tied into the character creation system: If you use the default character creation options, the resulting PCs will be inundated with scenario hooks for the sandbox. Unfortunately, the actual design of the sandbox mostly consists of scenario ideas that the GM needs to develop into fully playable material. I think this is a misstep: The space spent on the fully-developed scenarios would have been better spent fully-developing the Mystery Sandbox so that GMs could just run it out of the box.

It doesn’t help that the fully-developed scenarios are… questionable. There’s some cool ideas in there, but their continuity, structure, and content will frequently leave you scratching your head. I think my “favorite” moment is the scenario where the Kids are out in the middle of nowhere in the middle of winter, they stumble across a cabin, and the owner of the cabin basically says, “Would you kids like to take my car? Here are the keys. Make sure you don’t scratch it on your way to the next plot point!” Which is really weird.

There are a lot of these types of interactions which will leave you wondering whether the scenario authors have any actual understanding of how adults talk to children.

The setting and scenario material is not helped by the attempt, in the English language edition, to adapt the original setting (a small set of islands in Sweden) to an American alternative (a desert town in Nevada). This localization effort is carried out by placing American names in parentheses after the Swedish originals. For example:

- Riksenergi [DARPA]

- Gunnar Granat [Donald Dixon]

- Nordiska Gobi [Sentinel Island]

It’s a clever idea. The result, unfortunately, is an abysmal failure. First, the parentheses aren’t consistently executed, resulting in scenarios that are only half-way converted and creating an immense amount of confusion for the GM trying to keep frequently large casts of characters consistent. Second, it turns out that just swapping names isn’t enough to re-contextualize Swedish islands to American desert.

For example, one scenario features the wreck of a Russian mining ship. That makes sense off the coast of a Swedish island. In Lake Mead, however? That demands some sort of explanation… and none is forthcoming.

CONCLUSION

My initial experiences with Tales from the Loop leaned heavily towards the negative… but there was a spark of potential in there that tantalized me and brought me back over and over again to see if I could fan that spark into something greater.

I described the recommended procedures and approach I eventually figured out above. But my overall impression kind of boils down to the core mechanic: The reroll mechanics help. The rules for Helping help. A GM making extensive use of the Extended Trouble mechanics will help. Using narrative resolution techniques helps. But you still end up with a very tenuous bubble, and you’re still running headlong into some very hard limits based on some very limited resource pools that strongly curtail the flexibility of the system.

But even using all of these recommendations, we ultimately found the system to be… meh.

What I’m left with is a game which largely shares the enigma I found in D&D 4th Edition Gamma World: Is a really kick-ass character creation system enough to save an otherwise mediocre and/or broken gaming experience?

For Gamma World, my answer was Maybe… and then I never played it again.

Tales from the Loop seems to be a better game than that, so I will answer: Some times.

And I say that in large part because we found that the strengths of the character creation in Tales from the Loop extended deeper into actual play, resulting in some very emotionally powerful play. I also suspect many will find much greater utility (and even revelatory innovation) in the game’s Mystery Sandbox than I do. (It was certainly refreshing to see such an approach headlined so prominently and centrally in an otherwise mainstream RPG.)

Style: 5

Substance: 3

FURTHER READING

Tales from the Loop: System Cheat Sheet

Tales from the Loop: Nintendo Slugs