SPOILERS FOR CANDLEKEEP MYSTERIES

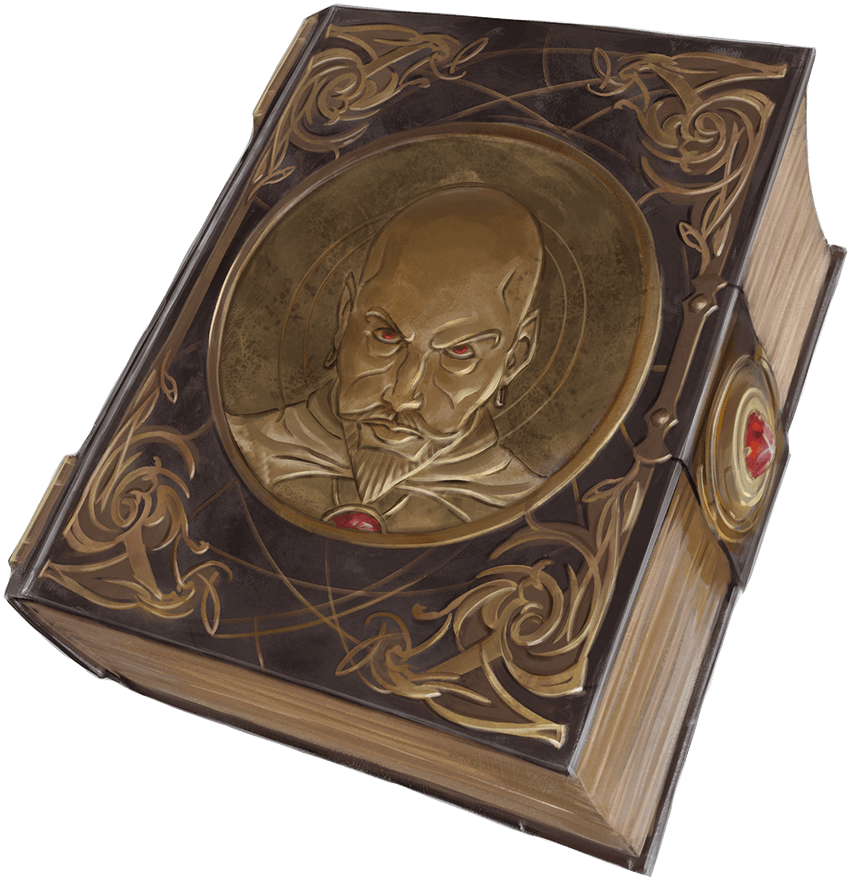

Candlekeep Mysteries is an adventure anthology for 5th Edition D&D featuring seventeen adventures — one each for every level from 1st to 16th (plus an extra one for 4th). The central conceit is that the hook for each adventure is a book: You find a book at the great library of Candlekeep. That book contains a mystery. You solve the mystery.

(The hook for the book is that the hooks are books? Try saying that five times fast.)

It’s a great premise. It gives the individual authors a huge amount of latitude in creating unique and imaginative scenarios. You can easily imagine an entire campaign where the PCs are a specialized team of acolytes or specialists working for Candlekeep to investigate new books being added to the collection (or resolving “cold cases” from the forbidden shelves), but it also makes it trivial to pluck out any one scenario and use it as a one-shot with the Dungeon Master having a huge amount of freedom in how they choose to actually use the scenarios: You can, after all, put a book basically anywhere.

It’s unfortunate, therefore, that the book so consistently fails to deliver on this promised premise. The problem is that Candlekeep Mysteries doesn’t trust the players to be tantalized by the strange mysteries at their fingertips. What if they open the book and — oh, no! — aren’t interested in it? So, with a few exceptions, every scenario in the anthology starts with a book… and then almost immediately has an NPC pop in to tell the PCs exactly what they’re supposed to be doing and often offering them a cash payment to do it.

The frequent result is an unnecessary railroad that simultaneously locks the adventure tightly to Candlekeep (since it now depends not on the book, but on a specific set of Candlekeep NPCs) and greatly limits the utility of the book. It’s particularly frustrating in those scenarios where the authors were clearly writing to the premise, but the railroad was then lathered on in development. In these scenarios, you get books with weird mysteries in them… and then an NPC pops into the room and solves the mystery for you before giving you a To Do List.

Despite this systemic failure, many of the adventures in Candlekeep Mysteries nevertheless succeed. In some cases, they succeed brilliantly. And so we’re going to take a look at each of them in turn.

CANDLEKEEP GAZETTEERS

Before we dive into that, however, let’s take a quick moment to look at the brief gazetteer of Candlekeep that’s included in the book.

If you’re not familiar with Candlekeep, it’s a library-fortress built along the Sword Coast in the Forgotten Realms. It’s the Library of Alexandria on steroids. In order to access the library, you need to offer Candlekeep a book which does not already exist in its collection. (This can be a great adventure seed in its own right.) Even after you’ve gotten your foot in the door, however, there are layers of secrets to be peeled away within the strange and labyrinthine buildings and vaults.

In 2020, about a year before Candlekeep Mysteries came out, there was a DMs Guild supplement called Elminster’s Candlekeep Companion. I reviewed the book in June 2020, and I thought it very, very good. So one of my first questions as I sat down to read Candlekeep Mysteries was actually: Will this book render the Companion by Justice Arman, Anthony Joyce-Rivera, M.T. Black, and others obsolete?

The answer: Not at all. In fact, I would say that it actually super-charges it.

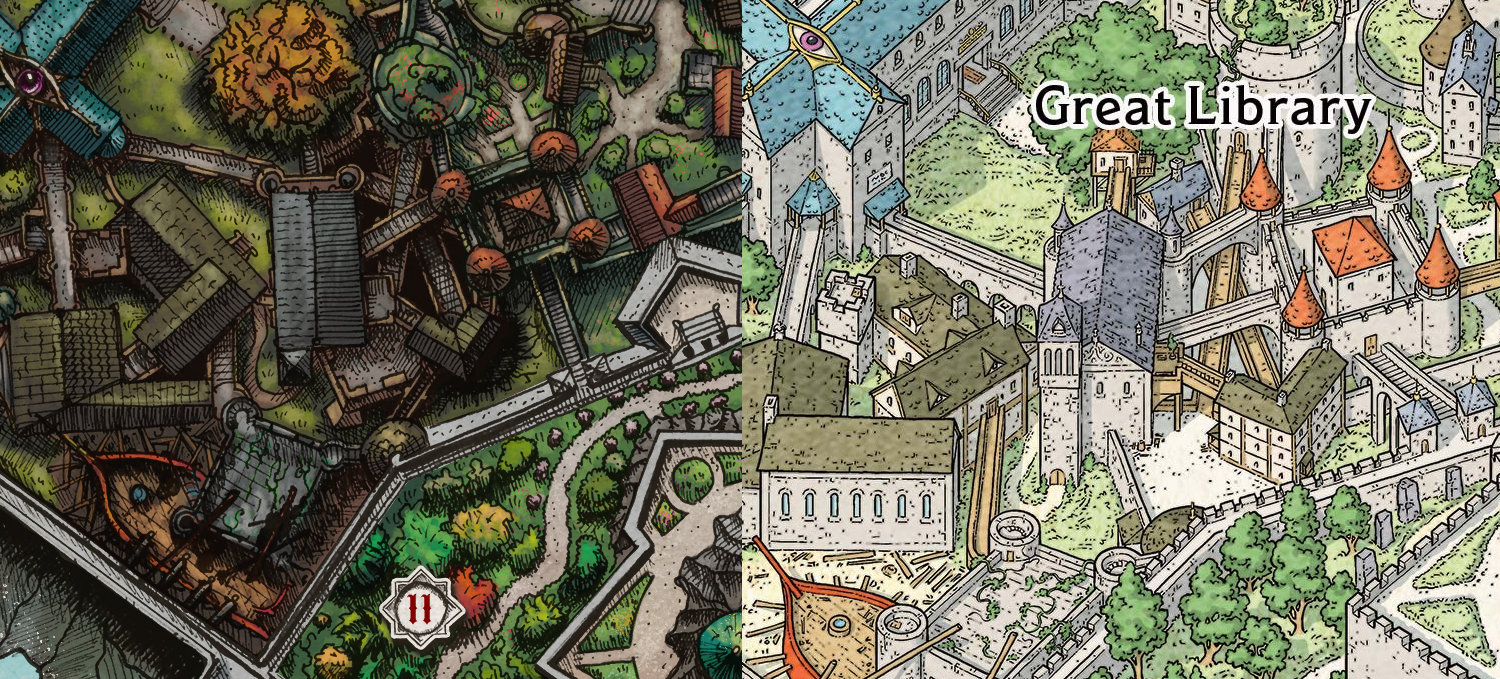

And this appears to be the thoughtful and intentional effort of the team at Wizards of the Coast. To take one simple, visual example of this, consider the incredible poster map created by Marco Bernardini for the Candlekeep Companion and the equally impressive poster map created by Mike Schley for Candlekeep Mysteries, as illustrated by these insets:

These maps are not just similar. It’s the same place mapped from a different perspective.

And the beautiful result is that both maps complement each other.

What’s true visually here is true in general: Candlekeep Mysteries provides a good, well-rounded briefing on Candlekeep as a setting. Elminster’s Candlekeep Companion goes deep, with a ton of play-oriented material that will add a ton of value to anyone running the scenarios from Candlekeep Mysteries.

I’m not here to regurgitate my review of the Companion, but check it out if you’re thinking about grabbing a copy of Candlekeep Mysteries. It’s like peanut butter and chocolate.

THE ADVENTURES

THE JOY OF EXTRADIMENSIONAL SPACES (Michael Polkinghorn) is a good scenario. The PCs come to Candlekeep to meet a researcher and find them missing. The subsequent investigation leads them to a hidden extradimensional sanctum, where they have to solve a puzzle to figure out the passphrase home.

The sanctum uses a hub-and-spoke design for exploration and is studded with flavorful environments. There’s a nice mix of roleplaying and combat encounters with the surviving experiments and constructs of the mage (although having a few of these encounters designed to go either way, instead of each being clearly designed for specifically combat or specifically roleplaying would have been appreciated).

The sanctum uses a hub-and-spoke design for exploration and is studded with flavorful environments. There’s a nice mix of roleplaying and combat encounters with the surviving experiments and constructs of the mage (although having a few of these encounters designed to go either way, instead of each being clearly designed for specifically combat or specifically roleplaying would have been appreciated).

There are a handful of continuity errors, but the one significant flaw here is that all of the PCs need to go through the portal together and get stuck. The scenario’s whole premise breaks if only one or two PCs go through first to scout things out: When the portal snaps shut, the PCs back with the book can just open the portal again.

Even if all the PCs go through the portal at the same time, all they need to do is tell someone at Candlekeep what the password for opening the portal is (or leave a note) and the scenario similarly breaks.

I’m honestly confused how this survived playtesting, and it’s not an easy problem to fix if you keep the metaphysics the way they’re set up in the adventure, but there are a few different solutions that aren’t too difficult to graft into place. So this should not, in the grand scheme of things, overly detract from the top line here: Good adventure.

Grade: B-

MAZFROTH’S MIGHTY DIGRESSIONS (Alison Huang) is a really nice, tight scenario that demonstrates Huang’s trademark style of layering complexity into her antagonists: The PCs are sent to investigate some criminals who are indirectly defrauding Candlekeep and putting people in danger. Except it turns out the criminals aren’t aware of the true dangers of their actions and their motivations are closer to desperate altruism.

Except it turns out the criminals aren’t aware of the true dangers of their actions and their motivations are closer to desperate altruism.

… until you take a closer look and all the ethics turn murky.

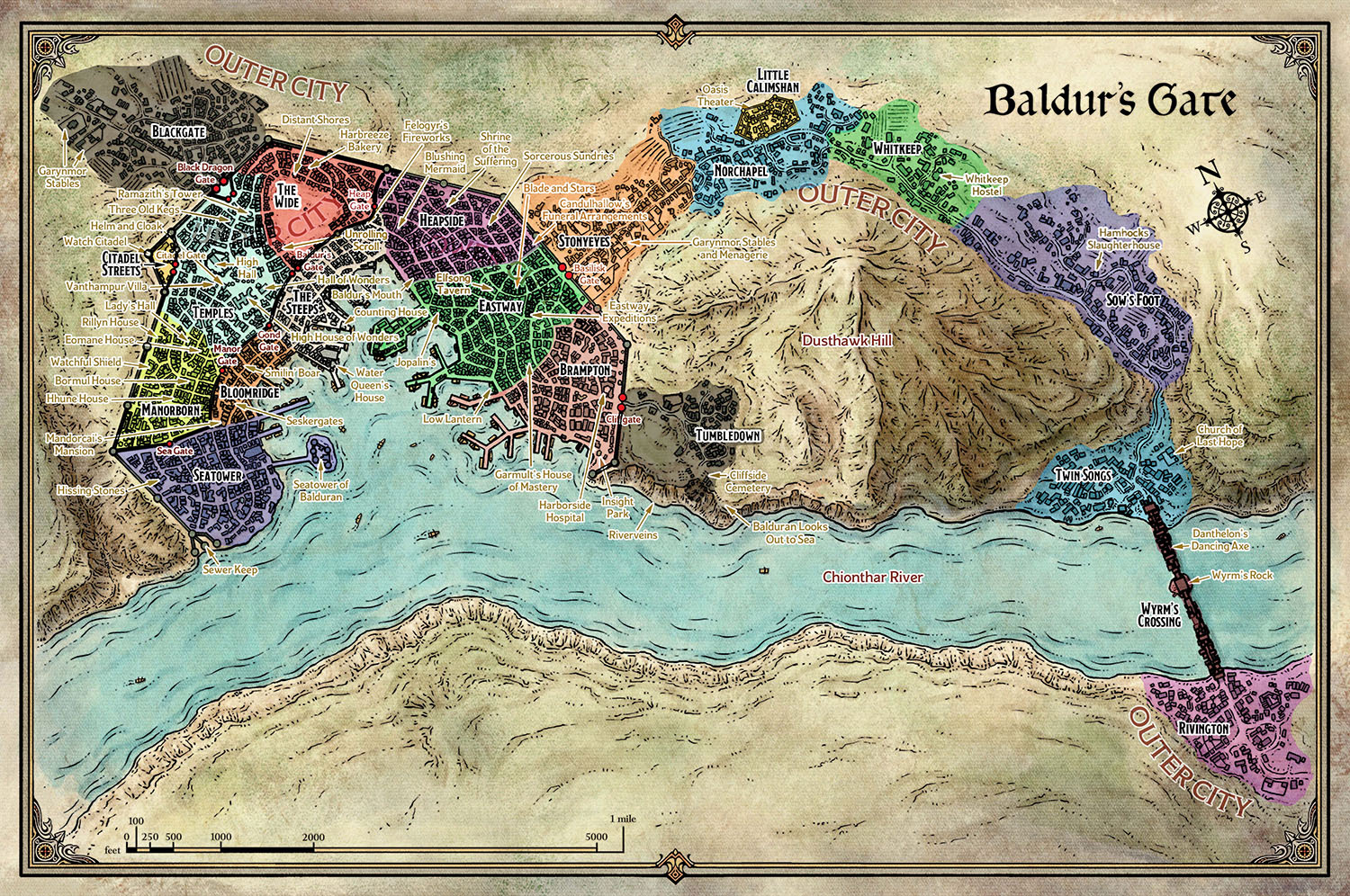

The hook is that the PCs are attacked by a book that they’re reading in Candlekeep. It turns out that this is the third such incident in recent weeks, all occurring with books that have recently been donated to the library. When the PCs investigate the source of these books, the trail leads them back to a bookseller in Baldur’s Gate.

(You could experiment with this hook by having the book that comes alive and starts attacking people be the one that the PCs themselves submitted to gain entry to Candlekeep! This would sacrifice some of the intrigue, since the PCs would know where they got the book, but crank up the stakes on the hook, since the PCs would now be responsible for the situation.)

The meat of this scenario, as I say, is that there’s no simple or straightforward solution. The villains aren’t villains (except they are?), and it’s not hard to imagine the PCs getting themselves tangled in knots trying to unravel the complications here. It’s an elegant bit of adventure writing.

Grade: B

BOOK OF RAVENS (Christopher Perkins) is, to put it bluntly, bafflingly bad.

The first thing to understand is that this isn’t really an adventure. It’s more of an extended scenario hook: “Book of Ravens” leads the PCs to an isolated chateau where they can be recruited by a secret guild of wereravens who monitor the Shadowfell and fights its evils.

There’s nothing wrong with setting up an entire campaign premise.

The problem is that literally nothing in the scenario makes sense.

Let’s start with the hook: The PCs find a treasure map in a book that leads to the chateau.

Why is the map there?

Well, 150 years ago a member of the wereraven society decided that they should recruit new members by putting the map in an obscure book at Candlekeep on the off-chance that somebody reading the book would (a) follow it and (b) be the sort of person to join their secret society.

That’s not necessarily the worst marketing idea I’ve ever seen, but…

Actually, no. That’s definitely the worst marketing idea I’ve ever seen.

And I guess the proof is in the pudding here because no one HAS found the map in the past 150 years. Although maybe this wereraven society was running a huge ARG and these TR3AZURR MAPZZ were being spammed everywhere. Outhouse in Daggerdale? Treasure map in the toilet paper! The Well of Entry at the Yawning Portal was choked full of them. This map is just the forgotten detritus of a huge 14th century fad.

Okay, regardless: Treasure map! Treasure maps are cool! Puzzling them out! Figuring out how the map relates to the territory! Following a treasure map is a cool adventure!

… one that they didn’t include in this book. “Book of Ravens” instead chooses to literally say, “Please design this adventure yourself.”

Hmm. All right. That’s fine. The real focus is on getting recruited by the wereravens, right? And the bulk of the scenario is dedicated to describing the secret sociey’s cool chateau hideout in detail. If you decided to embrace this campaign concept using, say, the Ravenloft sourcebook, having all this detail for the society’s hideout would be really useful!

… if any of it made a lick of sense.

Which it doesn’t.

First, at least 150 years ago (because that’s when they ran the ineffectual ARG) everyone in the chalet died and the wereravens moved in. But, despite living there for 150 years, they’ve done literally nothing to fix the place up: Every single room still lies in decaying ruin as a testament to the Brantifax family who built the place and then died in various gothic tragedies.

150 years! Multiple generations of wereravens!

Second, the wereravens came to the chalet because there’s a shadow crossing into the Shadowfell here. They monitor the crossing, keeping tabs on whatever crosses over.

… except the end of the scenario reveals that the shadow crossing has literally never been used. Not once. Not ever.

The wereravens have been monitoring a closed, unused door for One. Hundred. And. Fifty. Years.

Third, the wereraven society’s modus operandi is to find evil magical items and secure them, removing their evil from the world. When the PCs arrive, in fact, the society is currently discussing what they should do with an evil statue of Orcus that they’ve just gotten their claws on.

If the PCs don’t interrupt the meeting, the ravens conclude that the statue should be hidden here in the chalet.

Three important facts:

- They’ve been doing this for 150+ years.

- They hide the items they find in the chalet.

- There are no other such items at the chalet.

… is this literally the first time they’ve ever done this?

In any case, this is how the scene plays out:

Wereraven 1: We should hide it here in the chalet.

Wereraven 2: Good idea!

And then Wereraven 2 hops over to the corner of the room, drops the statue on the floor, and piles some random rubble on top of it.

Job done!

(There’s rubble lying around, of course, because, once again, they’ve done literally zero cleaning in the chalet for the past 150 years.)

This is unusable nonsense.

Grade: F

A DEEP AND CREEPING DARKNESS (Sarah Madsen) is one of the best scenarios I’ve seen in recent years. It’s actually been awhile since I read an adventure I would run without making any changes and it’s a pleasure to find one here.

In “A Deep and Creeping Darkness,” the PCs are hired by a mining consortium: A few decades back there was a small village with a platinum mine that was abandoned. The consortium has found the records detailing the mine, but they don’t know why it was abruptly abandoned. They have, however, heard that there’s a trove of documents from the survivors that was deposited at Candlekeep and they’d like the PCs to investigate and determine if it’s safe to the re-open the mine.

When the PCs go to investigate, of course, they have an opportunity to end the horror which plagued the mining village in its final days.

What makes this scenario sing are the personal stories that Madsen laces into the experience. These stories are layered, but also presented in myriad ways: A journal. Meeting with survivors. Clues in the ruins themselves.

Even better, the PCs are invited to become a part of these stories, bringing closure to the tangled emotions, painful enigmas, and unfinished business of those final, chaotic days.

Meanwhile, in a contrapuntal rhythm with these stories of loss and nostalgia, Madsen weaves a creepy horror laced with suspense: The events of the past begin to echo into the present as the same horror threatens to sweep over the PCs.

And then, of course, there is the ultimate closure, as the PCs end the horror which destroyed the town and, ultimately, help to bring the town back to life.

It’s just fabulous stuff.

The only thing I’ll flag is a small bit of undisclosed homework for the GM: A NPC named Lukas “can give them a rough map of the village.” But no such handout is included in the published adventure, so you’ll want to take a few minutes to sketch it out. (It’s probably also worth working up the titular journal that the PCs find at Candlekeep as a lore book handout.)

Grade: A