The adventure support for Mothership is out of this world.

(Pun intended.)

Mothership is a sci-fi horror RPG, inspired by films like Alien, The Thing, Annihilation, and Event Horizon. It takes a lot of inspiration from the Old School Renaissance, but it also pulls in a lot of new-fangled ideas from games like Apocalypse World. The result is a fast-paced, high-octane system that can somehow support both high body count slaughterfests and deep, long-term campaign play.

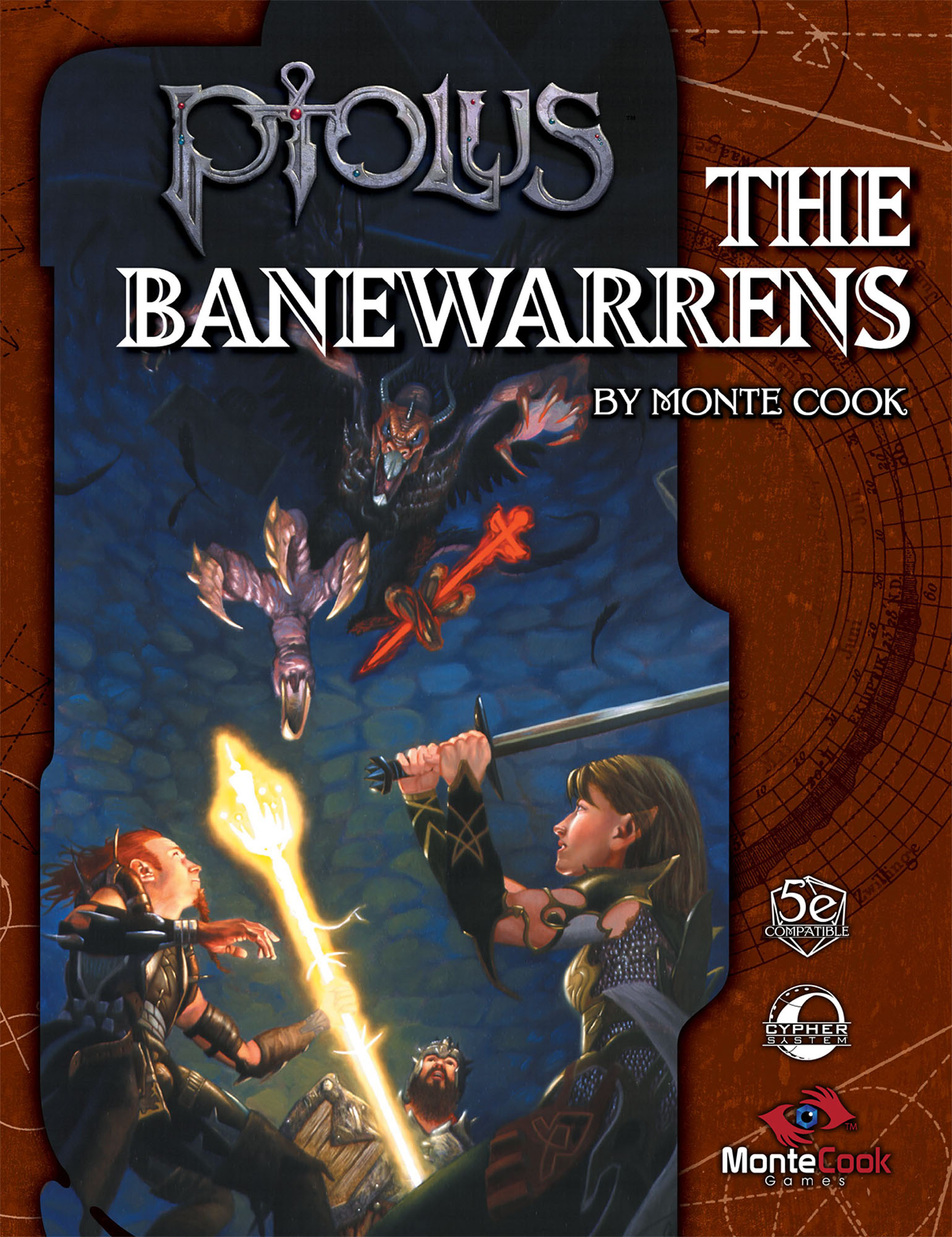

What I want to focus on right now are the plethora of trifold modules available for Mothership. Each of these is just two pages long – printed on two sides of a single sheet of paper and designed to fold up into a trifold pamphlet.

These are similar to One Page Dungeons and Monte Cook Games’ Instant Adventures. The intention is that the GM can grab one of these, read through it in just ten to fifteen minutes, and then immediately run it. They make it so that playing an RPG can be a spur-of-the-moment decision, no different than grabbing a board game.

And Mothership is an ideal game for this type of adventure support because character creation is lightning fast. You can take a group of complete newbies, teach them the rules, and have them roll up their characters in ten minutes or less.

Whether you’re looking for something to on a rainy day; need a pickup session because a player canceled at the last minute; or are just burned out on elaborate campaign prep and looking for something simple to run, these trifold adventures are a godsend.

This review is going to cover all of the first-party trifold adventures released by Tuesday Knight Games. Most or all of these exist in two forms: A 0E version designed for use with the original, “pre-release” version of Mothership, and an updated 1E version compatible with the boxed set. (I’m reviewing the current 1E versions.) Each is available in both PDF and physical formats.

Before we get started, let me share a couple of notes on potential biases here.

First, I got my copies of these adventures as a backer of the Mothership Kickstarter campaign. So I paid for them, but they did kind of feel like cool bonus content. With that being said, I will be trying to judge them with an eye towards what it would cost for you to buy them ($5).

Second, I’m planning to run Mothership as an open table. The primary reason for this is because the trifold adventures are so ideal for an open table – just grab one and run it for whatever group shows up each night – but it does mean that as I’m reading, evaluating, prepping, and running them, I’m definitely thinking about how they can fit into that open table.

SPOILERS AHEAD!

CHROMATIC TRANSFERENCE

Our first adventure, Chromatic Transference, is a riff on H.P. Lovecraft’s “The Colour Out of Space,” but venue-shifted to an abandoned secret laboratory built inside an asteroid.

I’m a big fan of “The Colour Out of Space” (see my own The Many Colours Out of Space), so this is right up my alley. Reece Carter makes the most of their material, presenting a delightfully creepy nine-room location crawl coupled to an excellent treatment of the strange colour and its mind-rending / body-altering effects. (It’s notably well-integrated with the mechanics of Mothership and also gives the GM excellent support for responding to PCs attempting a scientific inquiry into the colour.)

The only real weak point of Chromatic Transference is that it’s lacking any kind of scenario hook. Given the strong, iconic nature of the premise, though, you shouldn’t find it terribly difficult to brainstorm some options:

- The PCs are hired by the Corporation. They recently bought out a smaller company and, while sorting through the assets, discovered records of an abandoned research base. They’d like the PCs to go check it out. (Maybe accompanied by a corporate assessor?)

- The ship’s sensors detect the dormant docking bay of the asteroid base while the PCs are on a cargo run… do they want to go check it out?

- While sorting through a mass of data they pulled out of Aerodyne’s computers, they stumble across references to the asteroid research facility.

- They’re trying to track down Dr. Everton, who’s been missing for several years. They finally find records indicating that he was sent to a top secret research facility built into an asteroid.

However you decide to use it, the quiet horror of Chromatic Transference makes it a perfect pace-change from blood-drenched bug hunts, while the high stakes risks of allowing the colour to escape the facility – which the PCs may only figure out after it’s too late – ensure that the adventure will be a memorable one.

GRADE: B+

CRYONAMBULISM

A microbial parasite has infected the ship’s cryopods, trapping the PCs in a nightmare-infused hypersleep.

Things begin with the PCs “waking up” at the “end” of their journey. The nightmare version of their ship that they end up exploring is very smartly presented in a modular system that makes it easy to swap out rooms on whatever ship the PCs might be traveling on.

The core gimmick of the adventure – by which the PCs “wake up” one sense at a time (so that, for example, their eyes might be seeing the real world while their ears are still hearing the nightmare; or vice versa) – is a brilliant twist, elevating the kaleidoscopic action to a whole new level. (While also proving a very unique challenge to actually run.) The melding of real world and nightmare world also keeps all of the PCs involved in the action.

Ian Yusem also does a good job of considering how android PCs fit into the scenario’s biological threat. (For a game where Android is one of the four core character classes, a surprising number of adventures just kind of blindly assume all of the PCs will be human.)

If you’re running a Mothership campaign, Cryonambulism is the perfect filler episode: Don’t have the next adventure prepped yet? Good news! As the PCs blast off to their next destination, you can just hit the pause button by having the nightmare parasite infect their hypersleep!

On the other hand, I’m a little more skeptical about using this adventure as a stand-alone one-shot. The setup for the adventure seems to work best if the players are a little disoriented and uncertain about what’s happening. (Did we actually arrive at the destination and our ship was bizarrely wrecked in transit? Or is something else going on here?) And a lot of the payoffs feel like they’ll land a lot better if the players are more familiar with (and personally attached to) their ship. As a stand-alone, I think it can still work; but I think it’ll also be a tougher sell.

GRADE: B-

HIDEO’S WORLD

Hideo K designed a video game console that lets you play video games in your dreams. Unable to mass produce it, Hideo hooked himself up to his prototype and put himself into a drug-induced coma where he could live in the game world he’d created forever. To wake Hideo up, the PCs will need to enter the game world themselves!

This adventure doesn’t do it for me.

For starters, the lack of a scenario hook really hurts here: No reason is given for why the PCs might be motivated to seek out a washed-up video game developer. And when you start thinking about the premise to gin up your own scenario hook, you quickly realize that there are a lot of unanswered questions. (For example, where is Hideo’s body?)

Unfortunately, once you’ve entered the game world, it doesn’t get better. Hideo is supposed to have been trapped in this world for years or decades, but, of course, in just two pages you can’t really describe a world with a scope that would sell that idea. Most of the module actually describes the game’s main menu, and the rest is a single tower with eight rooms which is apparently the entirety of the game world.

This also contributes to the game world just not being very interesting, which is kind of a death knell for this sort of adventure. There’s possibly a weak stab in the direction of satire and also a friendly wave in the direction of Inception’s dream world logic, but there’s a lack of a strong, coherent vision.

I should also mention that Hideo’s World also comes with an audio file representing the soundtrack of the virtual world. This is okay, but has the pretty typical problem of many tabletop soundtracks of being too short: Do you really want to listen to three minutes and thirty seconds of video game menu music on a loop for a couple of hours?

GRADE: F

It occurs to me that you might be able to make a bit more sense of all this if you ditch the idea of Hideo being trapped for years and instead make the machine a prototype device whose code has been corrupted by Hideo’s subconscious mind. Then you could have his investors hire the PCs to go in and pull him out. Or, in a long-running campaign, you could even set things up by having Hideo pitch the idea to the PCs after a big pay day and try to get them to invest. That’s a lot of remixing for a two-page adventure, though.