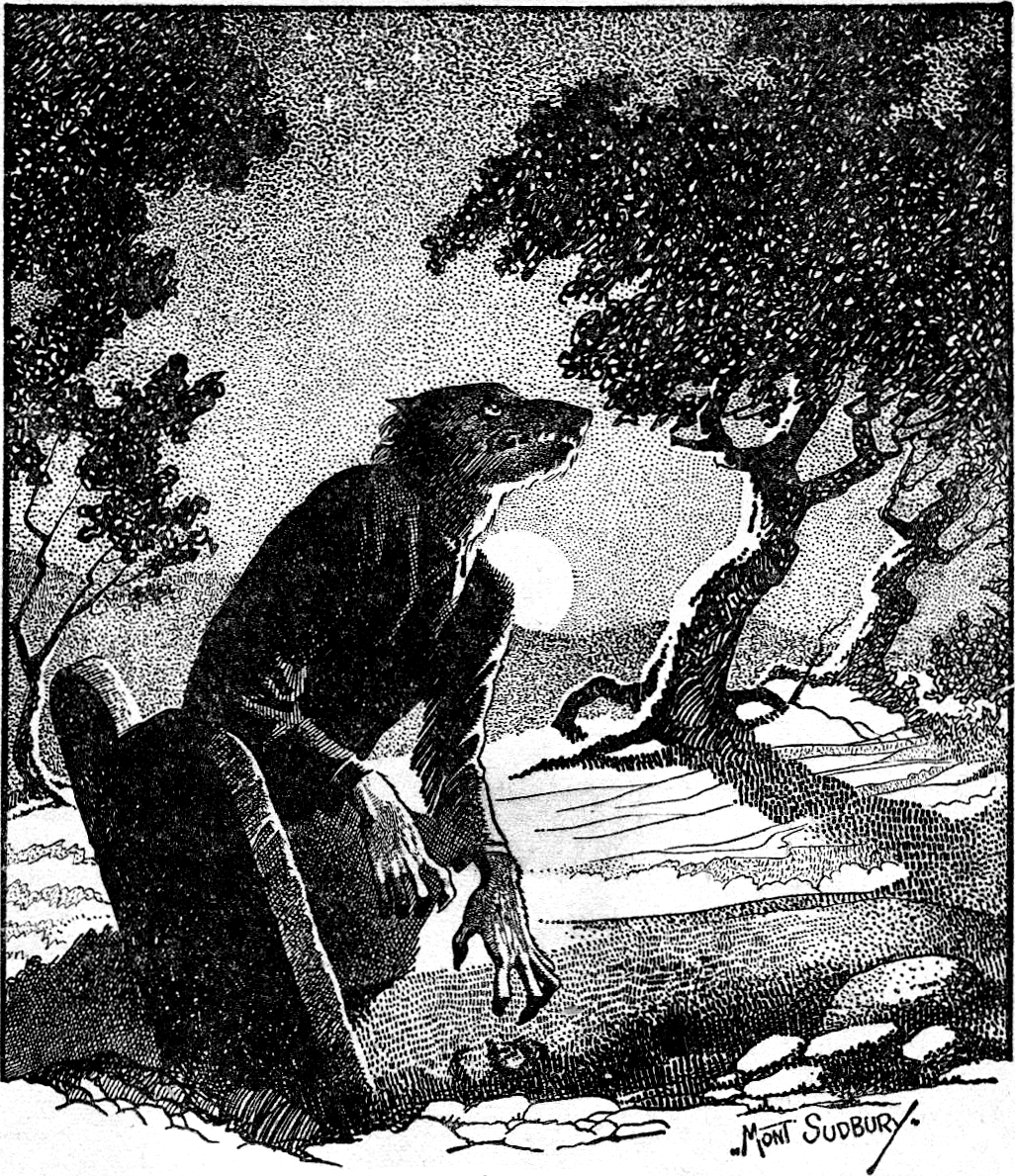

Let’s say that you have a scenario featuring a pack of werewolves that have taken up residence in a ruined castle a few miles away from a small village. What scenario hook could you use to get the PCs involved in this scenario?

Let’s say that you have a scenario featuring a pack of werewolves that have taken up residence in a ruined castle a few miles away from a small village. What scenario hook could you use to get the PCs involved in this scenario?

Perhaps:

- The villagers could ask them for help, or perhaps a local burgher could offer to pay them to root out the werewolves. (This is an example of patronage; an NPC is requesting that something specific be done.)

- The PCs could hear rumors in the local tavern about the spate of recent werewolf attacks, or perhaps they see bounty notices posted by the local sheriff. (This is an example of an offer; the GM is simply offering information and it’s up to the PCs to determine what they want to do with that information, if anything.)

- As the PCs ride past the ruined castle, a couple of the werewolves come racing out to attack them. Or perhaps they hear screams of terror emanating from a farmhouse. (This is a confrontation; the scenario is directly encountered by the PCs.)

In each case, the PCs generally come away with a basic understanding of the situation and an understanding of what action they’re expected to take: There are werewolves in the ruined castle and they need to get rid of them. (With some of the hooks they might only know that there are werewolves in the area and need to do some investigation to identify the ruined castle as their den, but that still constitutes a general understanding of the situation. It’s also possible, of course, for the PCs to choose a course of action that doesn’t involve getting rid of the werewolves: But when you design a scenario with slavering werewolves who are killing innocent people, it’s fairly clear what the expected decision will be.)

This, however, is not a necessary characteristic of a scenario hook. In each case, you can twist the scenario hook by misleading the PCs regarding either the situation or the expected course of action or both.

For example, you might mislead them regarding the nature of the threat: The villagers, discovering dismembered limbs and unfamiliar with lycanthropic activity, think that the attacks signal a return of the tribe of cannibalistic ogres who plagued the region a generation ago. That’s what they tell the PCs, who will be unpleasantly surprised — and perhaps wish they had stocked up on silver weapons! — when they head out to the ruined castle and discover the truth.

You might also mislead the players regarding the motives of the various NPCs involved. For example, it turns out that the werewolves in the ruined castle have actually come to the area to END the attacks by hunting down their former packmate who is now suffering from silvered rabies.

Or when the werewolves come rushing out of the castle towards the PCs, it’s because they’ve just escaped from the hidden torture dungeons of the local baron, who is transforming innocent villagers into werewolves to build a powerful, supernatural army. Reversing good guys and bad guys like this is an extreme example of the principle.

When NPCs are involved in delivering the misleading scenario hooks, it can be useful to distinguish between whether the NPCs are deceiving the PCs or if it is, in fact, the NPCs being deceived (or mistaken) about the situation: If the villagers know that the werewolves are just peaceful nature-lovers and they want the PCs to eliminate them so that they can claim the werewolf clan’s ancestral property in the valley, that’s a very different story from the villagers honestly believing that the werewolves are guilty of horrible crimes.

The possibilities are basically endless, and can obviously vary greatly depending on the actual details of the scenario in question.

The reason to use these misleading scenario hooks is because you’re creating a reversal: The players enter the scenario thinking that it’s one thing, and when they discover the truth the entire scenario changes into something new. In practice, delivering a strong reversal like this can turn even an otherwise pedestrian scenario into a truly memorable one.

MULTIPLE MISLEADING HOOKS

Having multiple hooks for the same scenario is a good idea, for the same reason that the Three Clue Rule is a good idea in general. Ideally, you want each of these scenario hooks to be distinct: Coming from different sources. Including different (although probably overlapping) information about what’s going on. Being driven by different motives.

(It’s less interesting for three different villagers to all follow the same basic script in asking the PCs to help them fight the werewolves. It’s more interesting if they see werewolf tracks in the forest and then a villager asks them for help and then they spot a poster offering to pay a bounty for werewolf pelts.)

When some or all of these scenario hooks are misleading — particularly if they are misleading in interesting and different ways — it not only becomes much easier to vary the hooks, it immediately creates a sense of mystery that will tantalize the players and encourage them to engage with the scenario in order to figure out what the heck is going on.

THE BAIT HOOK

The other form of a misleading scenario hook is one that is only “misleading” from a metagame perspective: This “bait hook” can be completely legitimate from the perspective of the game world, but the reason the GM includes it is in order to put the PCs in a position where they can be confronted by the true scenario.

For example, they might be hired to guard a package of diamonds that’s being delivered to a bank vault. But the only reason that job exists (and it might even go off without a hitch) is to put the PCs in the bank when the bank robbers show up.

On rare occasions, bait hooks like this can also be diegetic when an NPC gives the PCs a false job offer in order to maneuver them into a location or situation for an ulterior purpose. This plot conceit is quite common in pulp fiction, for example, when detectives are hired to keep a person or location under observation so that they can be framed for a crime.

I’m having a hard time understanding the difference between an “offer” and “patronage”. Does patronage relate to the NPC in question being proactive and pursuing the PCs instead of the reverse?

If so, would “confrontation” involve the scenario (or it’s elements) coming to the PCs? In this case, the opposite would be impossible without either an “offer” or “patronage” first.

I got confused because of the “bounty notices posted by the local sheriff” example. It seems like “an NPC is requesting that something specific be done”. I know these are not strict definitions though, but my head likes to put things in boxes.

@Kaique If I understand correctly, the difference is that in patronage a specific known NPC has made a personal request specifically to the PCs, while an offer is an impersonal, open invitation to anyone who wants to do it. In the first case, there are unlikely to be rivals going for the same job, and refusing it will likely have consequences for the party’s relationship with their would-be patron. In the second case, the party can expect (or at least shouldn’t be surprised by) others going after the same bounty, and more importantly that the party is free to decline to get involved without any direct consequences for them.

The Dark Canuck has the right of it.

To expand a bit, the WANTED poster example is definitely lying in a gray area, but it’s the lack of an ask directed specifically at the PCs that makes me classify it as an offer rather than patronage.

To expand on that a bit:

– An offer is not specifically directed at the PCs.

– An offer doesn’t necessarily tell the PCs what they’re supposed to do.

– Patronage, if accepted, enters the PCs into a specific agreement to do X for Y.

The bounty poster DOES give the PCs specific instruction (“you’re supposed to capture/kill this bounty for a reward”), which is what puts it in a gray area.

But the fact that the PCs aren’t agreeing to do a specific task for a specific patron is, IME, the most significant thing in terms of how patronage/offers work in play.

Got it. Thank you guys!