I saw Blade II in the theaters with a large group of people. One of my enduring memories from that film is from the drive home, when a member of the group insisted on criticizing the film because its vampires failed to honor the rules of Vampire: The Masquerade. I thought it was bizarre that someone felt that one piece of speculative fiction should be bound by the rules of another.

I saw Blade II in the theaters with a large group of people. One of my enduring memories from that film is from the drive home, when a member of the group insisted on criticizing the film because its vampires failed to honor the rules of Vampire: The Masquerade. I thought it was bizarre that someone felt that one piece of speculative fiction should be bound by the rules of another.

I mention this because I’ve noticed that fiction featuring time travel seems to bring this behavior out in people who would otherwise find it ridiculous to, say, hold Short Circuit to the Three Laws of Robotics (or whatever). It seems that a lot of people have very firm ideas about how time travel is “supposed” to work and they’re very unhappy whenever a film violates those “rules”.

SPOILERS AHEAD

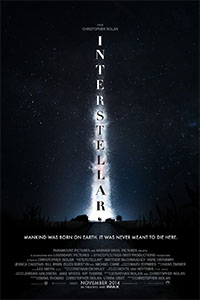

This is something I’ve mentioned previously while talking about the handling of causality in Looper. That made sense to me because the Looper’s version of time travel was so unorthodox and unique. But I was really kind of taken aback when Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar prompted similar outrage for its use of a pretty bog-standard bootstrap paradox.

For those unfamiliar with bootstrap paradoxes, they involve any situation where an event appears to cause itself. This most often occurs with information. For example, you send a message back in time to yourself and then, when the time comes, you know what message you have to send because you already received it. But… who wrote the original message?

It hurts your brain because you’ve spent your entire life living a temporally linear life, but it’s widely used in time travel stories. (In fact, sometimes it can seem as if it’s almost impossible to find a time travel story that doesn’t feature a bootstrap paradox.)

RESOLVING THE BOOTSTRAP

How can the 5-dimensional creatures in Interstellar create a wormhole that’s required for their own existence?

There are a couple of ways to resolve (or, perhaps, understand) bootstrap paradoxes and maybe relieve your headache.

First, assume that the linearity of time is an illusion. Interstellar talks about this in the form of time being a “canyon” that the 5-dimensional beings can climb into and out of: All of time exists simultaneously. This radically changes the concept of causality (possibly eliminating it entirely.) In this scenario the question, “How can they create a wormhole if they need the wormhole to create wormhole?” is like asking, “How can you drop a rock into the canyon if the rock will land at the bottom?”

Second, and perhaps slightly easier to grok, is the “hidden iterations” theory of establishing stable timelines with time travel. Take the scenario in Terminator, for example. We can imagine a first iteration of events in which causality proceeded normally: Sarah Connor had sex with some random dude from the 20th century and gave birth to a son who later led a rebellion. Then SkyNet tries to use time travel to kill her son, so her son sends Kyle Reese back in time. This creates a second iteration in which Sarah Connor has sex with Kyle Reese and gives birth to a different son who also grows up to lead a rebellion. The timeline is now a stable loop and no longer changes (until James Cameron gets a really cool idea for a sequel).

Similarly, one can imagine an “original” version of history where humanity’s space program never found a wormhole and decided to do something like colonize Mars instead: Most of the human race dies off, but our civilization survives and eventually evolves into the 5-dimensional beings. And then the 5-dimensional beings look back and say, “It still sucks that billions of people died on the planet of our birth. I think we can fix it, though.” And then they send the wormhole back through time and rewrite the history of their own creation (but this time without the mass extinction event).

Third, in the specific case of Interstellar, you can assume that there is no bootstrap paradox: Cooper is simply wrong about the 5-dimensional aliens being a future version of humanity. (One of the really great things about the film, actually, is that it features a lot of people being wrong about a lot of things…. or maybe being right about them, but in ways that the film is not interested in proving one way or the other.)

Complaining about the logic of time travel stories always seems like a bit of a pointless exercise to me. I accept the paradoxes as being part of the time travel conceit.

(I do think Looper is dumb but it’s because of what people in the setting do with time travel, not because of the rules of time travel presented by the film.)

I’m interested in seeing what Terminator 5 is going to be like because the trailer suggests that it is going to play around with time travel more than the previous films have done.

This is why I really enjoyed Primer (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Primer_%28film%29). You watch as the characters produce iteration after iteration of alternate pasts and struggle to produce stable alternates and even seem to discover there have been some hidden iterations they weren’t involved with.