Tagline: Power Kill questions some of the unspoken assumptions behind our entertainment in a pithy, biting, and utterly provocactive way.

Hogshead Publishing has, in my mind at least, successfully exploded without ever letting us hear the bang. As of this writing they are producing Warhammer Fantasy Roleplaying, SLA Industries, and the developing New Style line of RPGs (including Baron Munchausen, Puppetland, and Violence). If you haven’t heard of these, it is quite possible that you’ve been dead for the last two years.

Hogshead Publishing has, in my mind at least, successfully exploded without ever letting us hear the bang. As of this writing they are producing Warhammer Fantasy Roleplaying, SLA Industries, and the developing New Style line of RPGs (including Baron Munchausen, Puppetland, and Violence). If you haven’t heard of these, it is quite possible that you’ve been dead for the last two years.

(FYI: It’s March of 2000. Check with friends and families if you’re missing time. Besides temporary death, you may have also been abducted by aliens or the Illuminati or both. If this is the case, you’ve never heard of me, and I’ve never heard of you.)

But I digress.

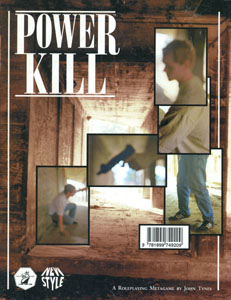

POWER KILL

Unspoken assumptions. Unquestioned premises. Unexamined beliefs.

There are things we hold to be such basic truths that we never stop to ask ourselves why we believe them – or to entertain the conjecture that it might be possible to believe in a contrary point of view. Often this poses no problem, but every so often you’ll find yourself in a heated argument with someone and neither one of you will quite be able to figure out why the other one isn’t “seeing commonsense”. Nine times out of ten it’s because you and your opponent are working from different premises – premises so intrinsic to the way you think about life that you don’t even hesitate to consider them.

A common example: Almost everyone believes that “murder” is an immoral activity – and they do so at such a basic level that they never really stop to ask themselves why murder is immoral, or even what murder is. Often this doesn’t pose any problems (no one really wonders whether or not Charles Manson was a murderer), but at the points where common belief frays (for example, do soldiers commit murder in war?) conflicts can arise without either party ever realizing where the true dissent lies.

This concept of unexamined premises can crop up pretty much anywhere – not just in debates about moral absolutes. Which, for those of you who are thinking I’ve gone completely off my rocker, brings us around to John Tynes’ Power Kill.

Power Kill is a “roleplaying metagame”, designed as an extra “layer of ‘game’ that you add to whatever Normal Roleplaying Game (NRG) you are currently playing”. In three short, hard-hitting pages it is a pithy assessment and satire of some of the unexamined beliefs which go into your common roleplaying session.

Basically it works like this: Everyone creates a “Power Kill Character” (PKC). There are no rules associated with this – just pick a name, gender, “race”, and background for the PKC (the setting is modern day Earth). You then “play” Power Kill in brief sessions before and after your normal roleplaying session.

In the session before play the GM (known in Power Kill as the “Counselor”) asks a few probing questions of the character played in the “NRG”. For example, “How many times a month do you find yourself in genuinely life-threatening situations?” These are filed in the PKC’s patient record, and play begins.

In the closing session the player assumes the role of the PKC. The Counselor spends a few brief moments describing the events of the roleplaying session in it’s real world context. For example, if the game session consisted of going into a dungeon and killing all of the monsters, then the Counselor explains that PKCs entered a low-rent tenement building inhabited primarily by ethnic minorities. “Moving methodically from room to room, the PKCs murdered the residents and took readily portable valuables such as cash, illegal drugs, and jewelry.” Once this summary is completed, the Counselor will again ask the PKC the standard set of Power Kill questions.

The Counselor should then analyze the two sets of questionnaires – comparing the assumptions of the PKC with the assumptions of the NRG character. Evidence that the answers of the NRG are closer to the PKC than to the delusional NRG personality are a good sign – it indicates that the schizophrenic PKC is beginning to associate more closely with reality.

“If the PKC refuses to refute the character in the NRG, continued therapy is required. If the PKC refutes the NRG character, but the player does not refute the PKC, continued therapy is recommended but not required.”

WHAT SHOULD YOU THINK OF ALL THIS?

There are two common refrains to the reviews and discussions concerning Power Kill that I’ve seen:

1. That Tynes is “biting the hand that feeds him” by criticizing the roleplaying industry as it exists. Worse yet, that Tynes is a woeful hypocrite. After all, just look at Delta Green — isn’t that exactly the type of game he’s criticizing in Power Kill?

2. That Tynes’ analysis of the roleplaying industry is “right on” – that any conscionable member of the hobby should reform their game-playing style in accordance with Power Kill’s criticisms.

Both of these suffer, I think, from a basic misconception of what Tynes is attempting to accomplish with Power Kill. The work, in my opinion, functions at two distinct levels – one simple, one complex:

At its more basic level, Power Kill is a rather humorous satire of some of the more recent trends in the roleplaying industry. A mock serious tone, bizarre and unusual acronyms and titles for the common roles of GM and player – the whole nine yards.

At its more complex level, however, Power Kill is an elegant (and, to a certain extent, eloquent) attempt to rip away the unquestioned exterior of the premises we bring to the table with us every time we sit down to a session of roleplaying. Why do our forms of entertainment basically consist of various forms of “crime fantasies”? “What is the source of our FAE [Fun And Excitement] anyway?” Why do we do these things with our spare time?

As he says in the summary at the end of the game: “Power Kill is meant to suggest a few answers. Or at least, to ask a few questions.”

I don’t think Tynes is, necessarily, saying that what we do in a typical roleplaying session is wrong – I think he merely wants to make us aware of what we do in a typical roleplaying session. Is this really what we want to be doing? If so, why? If not, why not? And even if we like what we’re doing now, are there other options we haven’t tried?

Awhile back, on one of the many discussion lists I participate on, someone asked the group why we all loved the work of Tynes so much. What makes his stuff so special? There were many answers – “his talent”, “his evocative settings”, “immense creativity”, “he’s a genius”, etc. (all of which are true) – but after giving it some thought I responded with an answer something like this:

Tynes doesn’t just write roleplaying games, he understands them.

We had been recently discussing his unfinished Stargate RPG (the notes for which you can find on his website, Revland), and I blundered on to point out the way in which Tynes was instantly capable of spotting the gaming potential in the Stargate universe, to target that potential, and then begin to design a game around it which accented, highlighted, and improved upon that potential.

The original questioner then asked me how Tynes did this. At the time I thought about it, but I couldn’t come up with an answer. After re-reading Power Kill a few times, though, I think I’ve finally figured it out:

Tynes doesn’t have any unspoken assumptions when it comes to roleplaying games.

Ultimately, I believe, Tynes is very self-aware. He doesn’t just let himself assume something — he asks himself why he holds that assumption, whether it’s a good assumption, what strengths that assumption has, and what strengths other options have (and in what contexts those strengths would manifest themselves).

Let me give you an example: One of the quickest ways to start a fruitless flame war in a roleplaying discussion group is to say one of two things – “Diceless games aren’t really roleplaying!” or “Dice ruin storytelling!”

The reason this will lead to a fruitless flame war (even if the original statement is made in a non-provocative fashion, rather than the belligerent tones presented here) is that you will very quickly have the two sides of this argument (the pro-diceless and the pro-diced) square off against each other – neither one ever really asking themselves what the relative merits and weaknesses of the two mechanical options are.

The real truth – and the truth Tynes, I think, understands – is that neither side holds the ultimate truth. For some things, dice is the better option. For others, diceless. If you move beyond your simple belief that, for example, “diceless games aren’t really roleplaying” to the question of why you think dice are essential for roleplaying (usually dealing with making the experience a “game” or introducing the “random factor” into the equation) you’ve made a good deal of progress.

If you take the next step and ask yourself: What about games which don’t use dice – can’t we base a roleplaying game in those traditions, too? What about situations where randomness isn’t necessarily an important component (or even a situation where randomness would be a downright substandard choice)? Well, at that point you’re on the verge of making some important breakthroughs (Baron Munchausen, Puppetland, and Amber being some key examples of innovative designs which have come about by such questioning).

I’ve been discussing rule systems, but this applies equally to world building, plotting, adventure design, character design, and pretty much anything else. You just have to learn to ask the right questions.

And I think, at the end of the day, that’s what the message of Power Kill really is: Asking the right questions, and seeing where the answers take you.

Or, at least, that’s the conclusion it’s questions took me to. Your answers might lead you somewhere else entirely.

Which is the whole point.

Style: 4

Substance: 4

Author: John Tynes

Company/Publisher: Hogshead Publishing, Ltd.

Cost: $5.95

Page Count: n/a

ISBN: 1-899749-20-9

Originally Posted: 1999/10/23

[ Note: Power Kill is packaged back-to-back with Tynes’ Puppetland game. Rather than do both games the disservice of attempting to review them together, I am instead going to review them separately. The page count listed for Power Kill is for Power Kill alone; the price is the cost of both games together. The review of Puppetland can be found here. ]

It was really fascinating re-reading this review nearly 15 years after I wrote it. There’s that section in the middle of it where I’m struggling to express the insight I had about Tynes’ fan-brewed Stargate game: Add ten years to those thoughts and you get my (hopefully much clearer and more useful) series discussing Game Structures.

Upon further consideration, I’m forced to conclude that this is probably one of the five best reviews I ever wrote. (Although that feels like a bit of a cheat because so much of it was prompted by the superb quality of Tynes’ work.)

For an explanation of where these reviews came from and why you can no longer find them at RPGNet, click here.

In an amazing coincidence, I had just started to read “Delta Green: Strange Authorities” on my phone this afternoon because I had put it in my limited number of items in iBooks. I actually don’t remember doing this, so there might be aliens or a conspiracy involved.

Fascinating idea. I think people often do game to gain a sense of power, but it is sometimes appalling what people fantasize about doing with that power.

In a way, the whole alignment schtick may have set us on the course of murder-hoboism in RPGs because the original Monster Manual quite clearly labeled which monsters were evil and therefore deserving of summary death. I think alignments also encourage playing “evil” characters rather then characters with more nuance. “Hey, my thief is chaotic evil, so I have to burn the village.” Enough rambling.

More importantly, here it is…

http://johntynes.com/revland2000/rl_powerkill.html

It started with missing livestock. A couple sheep, a foal, an old milk cow. Then the daughter of one of the local farmers went missing while fetching water. Every able bodied man, and not a few hardy women scour the glen in search of lost child. The heroes discover a set of strange tracks leading to a dark cavern. They venture inside the lair and slay a clutch of giant spiders that have been stalking the countryside. Within they find the desiccated remains of deer, sheep and two people: the lost girl and what appears to be the body of the sorcerer responsible for unleashing the horrors upon the land. In addition to some personal jewelry there is a jeweled dagger, a golden cup, and a polished silver mirror- treasures that no doubt were tools of the magician’s dark ritual. The heroes collect the riches so that no one else may unleash the monsters again, wrap up the girl’s body and return it to her family for proper burial.

Yeah, that sounds exactly like stalking a low-rent tenement murdering innocent black families for their jewelry and loose change.