Tagline: A really great card game, although with fewer twists than we’ve come to expect from Master Garfield.

THE CONCEPT

“’One day I will ride a horse like that,’ said the child to the woman as they watched the noble procession. ‘Yes dearie.’ ‘And I will have a palace, and lots of cake.’ ‘Maybe,’ she said, remembering the marble-lined halls of her youth. ‘But today let’s just to try to finish planting to the stream.’ The only place that peasant and princess change places faster than in a fairy tale is in The Great Dalmuti!”

“’One day I will ride a horse like that,’ said the child to the woman as they watched the noble procession. ‘Yes dearie.’ ‘And I will have a palace, and lots of cake.’ ‘Maybe,’ she said, remembering the marble-lined halls of her youth. ‘But today let’s just to try to finish planting to the stream.’ The only place that peasant and princess change places faster than in a fairy tale is in The Great Dalmuti!”

Life isn’t fair… and neither is The Great Dalmuti!

According to the introduction of the little multi-lingual instruction pamphlet of The Great Dalmuti (English, Spanish, German, and French rules are all presented in one), Richard Garfield first encountered the rules for this game while attending graduate school. As he says: “I had never seen a game like it before; it rewarded the player in the lead and penalized the player who was falling behind. The game was played for no other purpose than to play. There was no winner or loser at the end; there was only the longest-lasting ‘Dalmuti’, and the ‘peon’, the player most talented at grovelling.”

THE RULES

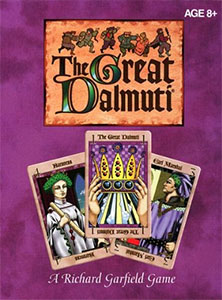

There are twelve ranks of cards. The ranks symbolize various levels in a fantasy society – with the Great Dalmuti at Rank 1; the Baronesses at Rank 4; Peasants at Rank 12; etc. The rank also doubles as the card’s effectiveness (with lower numbers being more effective) and as the number of cards of that type in the deck (thus there is one Great Dalmuti in the deck, four Baronesses, twelve Peasants, and so on ). There are also two Jesters, who are assigned Rank 13 – but can also act as wild cards when played in conjunction with other cards.

At the beginning of the game everyone draws a random card, which assigns their rank: The player with the highest card is the Great Dalmuti; the second highest becomes the Lesser Dalmuti; the lowest becomes the Greater Peon; and the second lowest becomes the Lesser Peon. Everyone in between becomes a Merchant (of varying ranks depending on where their cards fell).

Here’s the really cute part of the game: You have to change the seating arrangment according to your rank. The Great Dalmuti can stay where he is, but everyone else needs to array themselves out to his right, until you finally return to the Greater Peon to the Great Dalmuti’s left.

All the cards are dealt at this point (by the Greater Peon) and the goal is simple: Get rid of all your cards. Before play begins, though, is a stage of taxation – in which the Greater Peon gives his best two cards to the Greater Dalmuti in exchange for two of his cards (which the Dalmuti selects), and the Lesser Peon gives one of his cards to the Lesser Dalmuti in exchange for one of his cards.

The Greater Dalmuti then leads the first round by playing one or more cards of the same rank. Play proceeds to his right (through the Lesser Dalmuti to the Greater Peon) with each player being able to play either more cards of the same rank which was last played, or a set of cards in a higher rank. The round proceeds until no one can (or will – you’re not forced to play just because you can), and then whoever played last wins the round and leads the next.

The first player to run out of cards becomes the Great Dalmuti in the next round; the second player out becomes the Lesser Dalmuti; and so on until you reach the last player (who becomes the Greater Peon).

There are some other flairs (for example the ability to call a Revolution and an optional scoring system), but that’s the gist of the game.

SUMMARY

You may be asking yourself why you should buy this game. After all, I’ve told you almost all the rules; Garfield didn’t invent it; and you can play it with a regular deck of cards.

Well, quite frankly, because the deck of cards which is being furnished to you is really great – and cheaper than buying the several decks of cards which you would need to in order to assemble the specialized deck needed to play.

Win-win.

Which, of course, leads to the obvious question: Is the game worth playing?

Absolutely. The bigger the group, the more fun it is. It’s open-ended, while remaining competitive, and the interactions (both socially and strategically) which the dynamics of the rules lead to are really entertaining.

Garfield says one thing in the instruction manual that really captures, I think, why he has had such incredible success in designing (and, in this case, presenting) card games that capture the minds and hearts of their players: “If you’ve enjoyed The Great Dalmuti and don’t usually play regular card games, give them a try. For me there are more hours of amusement in a single deck of cards than in all the world’s movies combined. And I love the movies.”

Amen.

Style: 4

Substance: 4

Author: Richard Garfield

Company/Publisher: Wizards of the Coast

Cost: $7.95

Page Count: n/a

ISBN: 1-880992-57-4

Originally Posted: 2000/03/12

For an explanation of where these reviews came from and why you can no longer find them at RPGNet, click here.

I remember this game; we played it quite a lot when it first came out and it was a lot of fun. But not very long. We pretty soon went back to playing mostly Risk and Settlers when we had a group around. I wonder why, maybe just because we tended to have the time for a long game and you get enough of Dalmuti after a hour at the most.

I think we probably still have the cards somewhere at my parents house.

This is also one of the favourite games of Steve Jackson and Ian Livingstone, and they know a thing or two.

This is my go-to relaxed game for mixed audiences, particularly at parties where people are at various levels of intoxication; serious gamers can enjoy it and bring some strategy to it, and casual players have fun without feeling like they need to be strategic.

The more I think about it, it’s really the metagame that makes the game as fun as it is and not so much the rules of playing the cards itself. With the beginner keeping his seat and everyone else reshuffling around him, him getting a small bonus while the loser gets a penalty, and the loser having to deal the cards creates a lot of fun around the table. The effect on the game is almost nothing, but it adds so much satisfaction to winning a round and drama to being last.

Take note of this, RPG designers. Metagame considerations do make a difference for how fun your game is.

I just started reading the rules of Atlantis: The Second Age, and it specifically says to give experience for doing cool things immediately and not at the end of the game, to pour extra fuel on the flames when everyone is already excited about the cool thing that just happened in the game.

We played a game very similar to this during our high school lunch breaks. The game was played with just a regular deck of cards. The reward for winning finishing well in a given round, though, was the forced exchange of cards at the beginning of the next round. In a four person game, for example, the last place finisher would be required to give his two best cards (say, his only ace and one of his two kings) to the top place finisher. The last round’s winner would look at this bounty, then decide what two cards to dump off with the last place finisher. Play sounds similar, although you were required to match the number of cards in the set led. So a previous round’s lose might catapult to the lead with a timely played set of four twos, because no one else would have a four of a kind to play on it. Tremendous amounts of fun, even without the fantasy milieu.

Minor nitpick:

“with each player being able to play either more cards of the same rank which was last played, or a set of cards in a higher rank.”

The first of these is not actually allowed, at least by the rules in my copy. Each play must be exactly the same number of cards as was led, at a strictly higher rank than the last play.

This is/was one of my absolute favorite camping games as a kid! I haven’t had gaming groups large enough to play it in years but I still love it. We’d add the conceit of literally arranging seats so that the dalmuti’s was the best, most cushions, etc, and of course require that the peons act sufficiently deferential, and shuffle, and deal… I think as a kid it was really fun to have that element of “”roleplay”” and good natured teasing, and it was a good combo of luck and strategy.