Hamilton may be clearly wrong in identifying the Second Maiden’s Tragedy as the lost Cardenio, but there remains an important and lingering question: If the handwriting in the Second Maiden’s Tragedy manuscript does belong to William Shakespeare, what does that mean?

Well, it could mean that this is, in fact, a lost play by Shakespeare. It’s almost too easy to conjure up a hypothetical scenario in which Shakespeare and Fletcher, fresh from their success with Cardenio (assuming they actually wrote it), decided to pluck a different story from the pages of the popular Don Quixote and use it as the B-plot in a new play.

Or perhaps Shakespeare somehow ended up scribing the fair copy for one of the scripts purchased by his company. (And perhaps cleaning it up a bit in the process?) In the modern world it’s perhaps too easy to imagine that a shareholder would hold themselves aloof from such a “common” duty, but theater has always seemed to engender a spirit in which everyone pitches in to make the magic happen.

Or perhaps Shakespeare somehow ended up scribing the fair copy for one of the scripts purchased by his company. (And perhaps cleaning it up a bit in the process?) In the modern world it’s perhaps too easy to imagine that a shareholder would hold themselves aloof from such a “common” duty, but theater has always seemed to engender a spirit in which everyone pitches in to make the magic happen.

Another possible explanation would be that Shakespeare asked the company’s scribe to write out the fair copy of his will. (This assumes that Hamilton is wrong in claiming that the will was both written and signed in the same hand, but right in claiming that Shakespeare’s will and The Second Maiden’s Tragedy were.)

Of course, even if Hamilton is wrong about the handwriting entirely, some of his other conclusions may have merit. For example, he hypothesized that the play shows clear stylistic signs of having been a collaboration. W.W. Greg, in the Malone Society Reprint edition of the play, similarly hypothesized the potential for two literary correctors working on the manuscript (although both of those correctors were in hands different from the scribe’s).

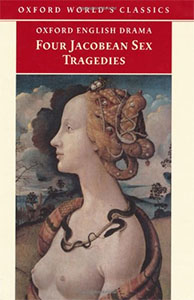

Hamilton is also likely right in believing that the play was never performed under the title The Second Maiden’s Tragedy. In Four Jacobean Sex Tragedies, for example, Martin Wiggins argues that even George Buc wasn’t referring to it as such. When he wrote “this second Maydens tragedy” he didn’t mean “this [play called] The Second Maiden’s Tragedy“; he meant “this second [play called] The Maiden’s Tragedy“ (in either case referring to the Beaumont/Fletcher play The Maid’s Tragedy written a few years earlier).

It’s certainly true that the script would have originally possessed a paper cover (now lost) which would have contained its proper title. In light of that, some have simply titled the play as they pleased. In Thomas Middleton: The Collected Works, for example, Julia Briggs published it as The Lady’s Tragedy (after the unnamed protagonist).

And it is, in fact, Thomas Middleton to whom the play is most commonly ascribed in a scholastic consensus which has, if anything, only strengthened over the course of the past decade in response to Hamilton’s claims.

For myself? Middleton seems like the most plausible candidate. I am occasionally teased by the thought that the play might be Massinger’s lost tragedy The Tyrant, but in this I think it likely I’m being led astray by the same temptation I suspect plagued Hamilton: To recover something precious which has been lost.

After all, Massinger didn’t start writing plays until two years after Buc had approved The Second Maiden’s Tragedy for performance.

Originally posted August 2010.