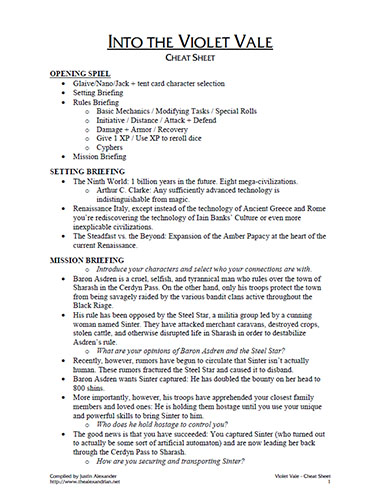

This adventure for Numenera is designed as a prequel to “The Beale of Boregal” scenario from the core rulebook. For my Wandering Walk campaign I felt the events of “Beale” would be enhanced if the PCs were already familiar with the aldeia of Embered Peaks and the peculiar properties of its numenera.

BACKGROUND

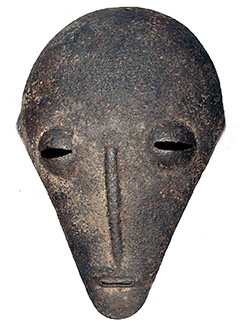

The kokutai is a hive religion made up from many different factions (each of which is also referred to as a kokutai). The kokutai as a whole is led by the Mask, a holy leader marked by his or her  face: A strange, mask-like biotech growth which extrudes into a faceless visage.

face: A strange, mask-like biotech growth which extrudes into a faceless visage.

Before their death, each Mask is supposed to reveal the identity of their next reincarnation in the form of a prophetic riddle. Solving this riddle (a process referred to as the Race of the Riddle) is meant to be a competition between the kokutai, with the winning kokutai (i.e., the one who finds the next incarnation of the Mask) receiving favor for their particular teachings within the religion.

The Seventh Mask, however, failed to deliver a riddle before his death. Some kokutai are interpreting this as a riddle in itself. The Bensal kokutai, however, have a different plan: They are carrying the body of the Seventh Mask to the aldeia of Embered Peaks, where it is said that the devoirs possess a machine which allows them to as a single question of the deceased. If they can uniquely receive guidance from the Seventh Mask through the devoirs, they’ll have an obvious and significant advantage in finding the Eighth Mask and securing their position of dominance within the kokutai.

THE MASK: If surgically detached, the mask functions as yesterglass when worn by another. (See Artifacts & Oddities 1, pg. 8.) The kokutai are unamused by this sacrilege.

THE HOOK

While traveling, the PCs spot the camp of the Bensal kokutai. Fassare, their leader, is concerned: Her scouts have disappeared and she has been receiving dreams of black prophecy during her meditations over the body of the Seventh Mask. She wants to hire the PCs as bodyguards and escorts to see the Bensal kokutai expedition safely through to Embered Peaks. She can offer them in payment:

- 20 shins

- Image Caster (L5 cypher, see Cypher Collection 1, pg. 6)

- Nectar Dispenser (L3 cypher, see Cypher Collection 1, pg. 8)

- Visual Diplacement Device (L5 cypher, see Numenera, pg. 297)

If the PCs push for more information, Fassare will tell them that she fears that they are being hunted by “apotheoite kokutai”. These false worshipers, according to Fassare, seek to find the Seventh Mask’s body and destroy it.

Alternative Hook: They could be directly hired to track down the Bensal and steal the corpse of the Seventh Mask. Their employer could be another faction of the kokutai (including those described below), a bizarre collector, or a time-traveling version of the Seventh Mask intent on creating a trans-temporal rumor (depending on how weird you want to get).

THE JOURNEY

1. BENSAL CAMPSITE: Where the PCs meet the Bensal kokutai for the firs time.

2. SCRUB BRUSH PASS: There’s a pass which cuts between the peaks here and heads straight to Embered Peaks. It has an artificial look to it and, unlike the surrounding landscape, is filled with scrub brush giving way to a brown and desiccated forest.It’ll cut time off the trip, but it gives unique opportunities for ambush.

3. GEYSER OF DUST: Going the long way around the mountains takes longer. Here you pass a geyser of dust which plumes perpetually thirty feet into the air. (It can be seen from about about 7 miles away.)

EMBERED PEAKS: Nestled in the palm of a mountain that looks like a giant seven-fingered hand (from which the town takes its name).

THE FIRST NIGHT

During the first night, the Bensal kokutai camp is attacked by six ravage bears. (This attack is a coincidence and has nothing to do with the hostile forces arrayed against the Bensal’s mission.)

If the PCs track the ravage bears back to their lair, they will find two ravage bear pups.

If the PCs track the ravage bears back to their lair, they will find two ravage bear pups.

RAVAGE BEARS (x6): L4, health 30, damage 7, armor 1

- Movement: Long

- Might defense L6.

- Runs, climbs, and jumps at L7.

- Ravage Grasp: Grab foes with powerful arms. Victim suffers 4 points of damage per turn in addition to damage from attacks.

- Fury: If it takes more than 10 points of damage, reduce defense by one step and increase attacks by one step.

- Blind: Immune to visual effects. Olfactory effects can confuse and “blind” it temporarily.

BENSAL KOKUTAI

The Bensal kokutai was favored by the Seventh Mask. Their leader is Fassare, who is intent on retaining her kokutai’s favor during the time of the Eighth Mask.

FASSARE: L5, health 15, damage 3, armor 1.

- Defend at L6.

- Resist mental effects at L6.

- Gain 4 Armor for 10 minutes via a force field device implanted in her cerebellum.

- Minor telekinesis (from same device).

BENSAL KOKUTAI WARRIORS (x8): L2, health 6, damage 4, armor 1. Speed defense L3 (due to shield)

OPPOSING FORCE: CARAL KOKUTAI

The Caral kokutai think the Bensal kokutai’s plan is a great idea… they just want to do it themselves. Their primary interest is taking control of the Seventh Mask’s body and taking it to Embered Peaks. (And if they have to do it over the dead bodies of the Bensal, that’s fine.)

ATTACK PLATFORMS (L8): The Caral have access to briefcase-sized cyphers that, when activated, separate into four parts which form the corners of a solid energy field that can be used to fly through the sky with 4-6 people.

- Energy Weapon: 8 points of damage. (The perimeter of the attack platform pulses, coalesces, and then expels the energyform.)

- Duration: 1d4 hours of flight

- Movement: Long

The Caral have three of these platforms, although they’re likely to only use two in their first attack.

MOORA: L5, health 15, damage 3, dual wields a pair of ray emitters. Moora dual-wields ray emitters.

- Ray Emitter – Concentrated Light (L8): 200 feet, 8 damage, 1 in 1d6 depletion

- Ray Emitter – Concentrated Light (L5): 200 feet, 5 damage, 1 in 1d6 depletion

CARAL KOKUTAI WARLORDS (x2): L4, health 15, damage 4, armor 3. Speed defense L6 (due to shield)

CARAL KOKUTAI WARRIORS (x12): L2, health 6, damage 4, armor 1. Speed defense L3 (due to shield)

OPPOSING FORCE: GATHA KOKUTAI

The Gatha kokutai believes that the Bensal kokutai’s plan is a sacrilegious corruption of the Seventh Mask’s body. They’re more bloody-minded than that the Caral and seek to wipe out the “Bensal apotheoites” and their “Bensal heresy”.

LIGHTNING FENCE (L5): The Gatha have four reality spikes (Numenera, pg. 293) which can be activated in conjunction to form a four-sided fence of lightning 15 feet high. Passing through the fence inflicts 5 ambient damage. (They’ll use the fence in an effort to divide the Bensal’s forces and, if possible, isolate the Seventh Mask’s Body.)

MIGALA: L5, health 15, damage 5. Attacks at L6. Resists mental effects at L6. Migala carries a bandolier of detonations. Roll on the Cypher Danger Chart (Numenera, pg. 279) once per encounter.

- 8 detonations (Numenera, pg. 284; determine randomly)

- Detonation (gravity) (Numenera, pg. 284)

GATHA KOKUTAI WARLORD: L4, health 15, damage 4, armor 3. Speed defense L6 (due to shield)

GATHA KOKUTAI WARRIORS (x15): L2, health 6, damage 4, armor 1. Speed defense L3 (due to shield)

A local chirog tribe has become aware of the Bensal’s pyred procession. Like all chirogs, they despise numenera. Because they consider the body of the Seventh Mask to be a numenera relic, they now seek to destroy it.

The pack leader does not speak, but is surrounded by a choir of three alpha males who speak for her in alternating voices.

CHIROG PACK MEMBERS: See Numenera, pg. 235.

PACK LEADER: L4. Has a mental attack that inflicts 4 Intellect damage (bypassing armor).

ALPHA MALES (x3): L5, health 18, damage 6, armor 4.

TACTICAL NOTES

This scenario should not be run as a simple string of three mass combats. The various kokutai and chirogs should use varied tactics; retreat in the face of unexpected danger or loss; and the like. A few thoughts:

- One group or another may attempt to suborn the PCs, either by convincing them that the Bensal kokutai are in the wrong or simply promising to pay more for their services.

- A kokutai group that has been badly damaged might try to parley with the Bensal kokutai. (Or ally with the other kokutai, allowing for a joint assault featuring both attack platforms and a second lightning fence.)

- The Bensal kokutai might ask the PCs to approach one of the harrassing apotheoite kokutai in order to form an alliance against a common enemy. (For example, the Gatha might be convinced to forgive their heresy and protect the Seventh Mask’s holy vessel from the chirog. Or the Caral might be convinced to help them drive off the Gatha in order to assure that the riddle of the Seventh Mask can be discovered.)

- The Caral might launch a stealth operation to steal the body (either during the night or while the PCs are distracted by an attack from another group). The scenario could turn into either tracking them down or racing them to Embered Peaks.

If the players are losing interest, it’s probably time to launch an all-out assault to finish things up. Or go the other way and have a kokutai appear on the horizon, give a ceremonial chant of mutual respect, and then leave (signaling the permanent end of the conflict).

Embered Peaks itself can make a good location for a final ambush. It will provide a distinct environment from the overland ambushes and encounters and you can get innocent bystanders involved and/or caught in the crossfire.

Note that the opposition presented here assumes that the Bensal kokutai will be assisting the PCs. (You may wish to use my rules for NPC allies.) Without assistance, PCs — particularly low-tier PCs — will find themselves rapidly overrun by the powerful factions seeking the Seventh Mask.

Tales from the Table: Precepts of the Seventh Mask in Actual Play