In Chapter 3: Fireball, an explosion kills nearly a dozen people in Trollskull Alley not far from the PCs’ front door. Their investigation takes them to Gralhund Villa, which is described in Part 2 of this remix.

WHAT HAPPENED:

- Dalakhar was attempting to meet with Renaer Neverember at Trollskull Manor. He was being tracked by the Gralhund, Zhentarim, Cassalanters, and possibly others.

- A small team of Zhentarim agents led by Urstul Floxin attempted to waylay Dalakhar as he came down Trollskull Alley.

- The Gralhund nimblewright, observing the scene from a nearby rooftop, used a necklace of fireballs to launch a fireball which kills Dalakhar and most of the Zhentarim agents, with the exception of Urstul Floxin (who barely survives, but is incapacitated).

- The Gralhund nimblewright jumped off the roof, dashed forward, rifled through Dalakhar’s pockets, and took the Stone of Golorr. It then ran off, returning to Gralhund Villa.

MOTIVATION: A core problem in this scenario is that (a) the PCs are not strongly motivated to investigate the explosion, (b) they are explicitly encouraged to NOT investigate the explosion, but (c) if they don’t investigate the explosion, the rest of the campaign doesn’t happen.

My recommendation is simple: Kill someone they care about in the explosion.

Who you choose to kill is going to be heavily idiosyncratic to your campaign. It’s really difficult to predict exactly which NPCs are going to resonate most strongly with the players during actual play. Honestly, it’s just as likely to be some random person that you improvised off-the-cuff. But here are a couple of possibilities:

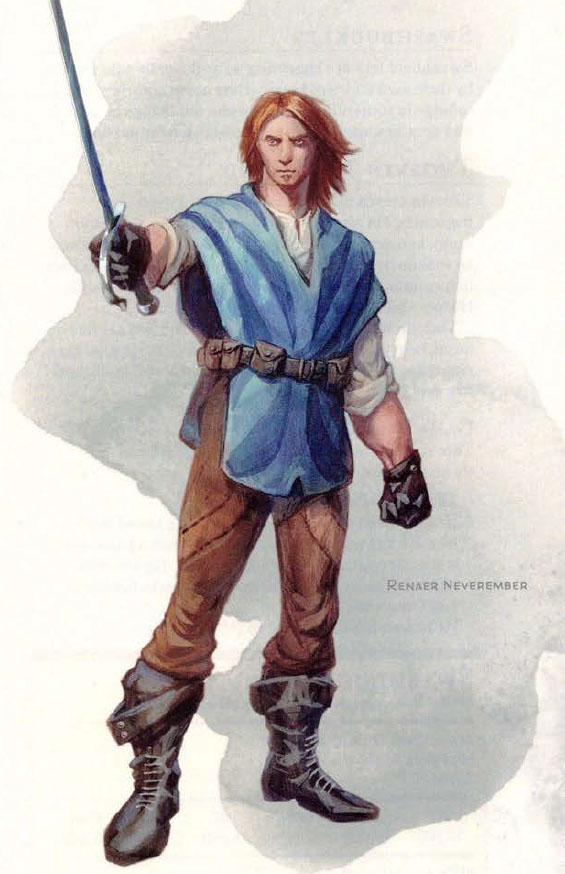

- Renaer Neverember. As described below, he arranged with Dalakhar to meet at Trollskull Manor. In this scenario, however, Renaer spotted Dalakhar on the street as they both arrived, approached him, and they were both killed in the explosion. (If you go this route, I recommend having a note from Dalakhar in Renaer’s pocket for the PCs to discover that will cover at least some of the information Renaer would otherwise impart.)

- One of the Three Urchins (see Part 3). If it’s not a deal-breaker for your group, introducing the cute little urchin kids and then killing one of them is virtually guaranteed to set the PCs on the warpath.

STRUCTURE: Generally speaking, this investigation will break down into three phases.

- First, the questioning of witnesses to the explosion. The primary revelation here is that a nimblewright was responsible.

- Second, finding and investigating known owners of nimblewrights. The primary revelation here is that they’re being purchased from Captain Zord of the Sea Maidens Faire.

- Third, either speaking with Captain Zord (aka Jarlaxle) or performing a heist (see Part 4B) to retrieve his customer information. If they perform the heist, they might also stumble across the crystal ball Jarlaxle is using to spy through the nimblewrights. Either way, the information will lead them to the Gralhunds.

THE CRIME SCENE: The crime scene is described on p. 44 of Dragon Heist.

- Add black flying snake tattoos to the Zhentarim corpses.

- Tracking the nimblewright? Physically tracking the nimblewright is not really feasible, its trail being quickly obliterated in the crowded streets of Waterdeep.

- Speak with dead? See p. 46 of Dragon Heist, but tweak answers to fit revised continuity where necessary. The key revelations from Dalakhar is that he was carrying the Stone of Golorr, what the Stone does (although he doesn’t know it’s been blinded), that he stole it from Xanathar, and that he was coming to meet Renaer. The key revelations from the Zhentarim is that they were seeking something that Dalakhar was carrying, they worked for Urstul Floxin, and they came from Yellowspire (see Part 3: Faction Outposts).

REMINDER!

During this investigation…

Don’t forget to have Renaer show up at the scene of the crime, probably 15-30 minutes after the explosion. When he does so, he’ll be able to tell the PCs:

Don’t forget to have Renaer show up at the scene of the crime, probably 15-30 minutes after the explosion. When he does so, he’ll be able to tell the PCs:

- That he had arranged to meet with Dalakhar at Trollskull Manor. The gnome had sent him an urgent message requesting the meeting and Renaer chose Trollskull Manor as the location.

- That Dalakhar was an agent working for his father.

- That his father had assigned Dalakhar to “keep an eye on me. He would skulk around and I would see him everywhere.” A few weeks ago, though, he abruptly disappeared and Renaer doesn’t know where he’s been. (If the PCs ask, it happened just before Renaer was kidnapped by the Zhentarim.)

- That he doesn’t know what Dalakhar wanted. “His message simply said that he was carrying something valuable for my father, was unable to deliver it, and was hoping that I could help.”

Don’t forget to have the Cassalanters contact the PCs and ask for their help in saving their children. It’s strongly recommended that this occur before they reach the Gralhund Villa.

PHASE 1: QUESTIONING WITNESSES

There’s generally three types of witnesses:

- Those who didn’t see anything, and merely relate their personal experience. (Heard a huge explosion, rushed into the street. Saw a friend immolated in front of their eyes and the heat of the flame on their face. All their windows blew out. Et cetera.)

- Those who saw the nimblewright throw a bead from a necklace of fireballs. (Variation: As described on p. 45, young Martem Trec recovered the spent necklace from where it fell in a rain barrel after the nimblewright tossed it away.)

- Those who saw the nimblewright approach Dalakahar’s body, take something from it, and run away. If the PCs inquire about which direction it went, the answer is between two buildings and heading east. (Variation: Some people may have also seen the nimblewright leap down from the roof from which it launched its attack.)

Which witnesses saw which events doesn’t really matter. The key revelation is that a nimblewright was responsible for the attack.

BONUS CLUE – THE HOUSE OF INSPIRED HANDS: One of the witnesses who saw the nimblewright remembers seeing a similar automaton participating in the Twin Parades yesterday as part of the Temple of Gond’s procession. (Following up on the Temple of Gond will lead to the House of Inspired Hands, see below.)

Option: There’s no reason the PCs couldn’t attend the Twin Parades themselves (see Part 4). If they do, you can describe several impressive processionals participating in the parade, including the nimblewright who was operating a number of wonderous mechanical contraptions. (If you want to force it, arrange for one of the PCs’ faction missions to require action during the parade.)

DESCRIPTION OF THE NIMBLEWRIGHT:

- A construct made of both burnished copper and pale wood.

- Wore a red robe and foppish red hat with a feather.

- A long, stylized Van Dyke beard. (This is unique to the Gralhunds’ nimblewright and may help identify it to Captain Zord later.)

- You can see its clockwork mechanisms constantly whirring and pistoning under its rune-etched skin-plating.

POTENTIAL WITNESSES

- Fala Lefaliir, owner of Corellon’s Crown (Dragon Heist, p. 32)

- Tally Fellbranch, owner of the Bent Nail (Dragon Heist, p. 32)

- Rishaal, owner of the Book Wyrm’s Treasure (Dragon Heist, p. 33)

- Jezrynne Hornraven, client of Vincent Trench (Dragon Heist, p. 45)

- Martrem Trec, 12-year-old boy and friend to the dead halflings (Dragon Heist, p. 45)

- Emmek Frewn, owner of Frewn’s Brews and rival (Dragon Heist, p. 42).

- Shard Shunners, gang hired by Frewn to interfere with the PCs’ business (Dragno Heist, p. 42)

- Ulkoria Stonemarrow, regular at Trollskull Manor (Dragon Heist, p. 42)

- The Three Urchins, particularly if one of them was killed (see Part 3C)

WITNESS – URSTUL FLOXIN: Urstul Floxin obviously survived the explosion, but he was badly hurt and will attempt to leave the area as quickly and surreptitiously as possible. If the PCs respond to the explosion quickly, however, they may have the time to briefly question him (particularly if they immediately move to assist the wounded).

- Somewhat disoriented, Urstul will give his real name if questioned.

- He’ll claim to have come to Trollskull Alley in order to go to (he glances around and points at a storefront) the Book Wyrm’s Treasure. He doesn’t know what happened; there was just a bright light and a lot of heat and he’s pretty sure he was knocked out.

- A DC 13 Wisdom (Insight) test suggests that he’s not being entirely truthful. If pushed, he’ll say, “Look, I must have been hallucinating. But just after the explosion, I could have sworn I saw a mechanical angel of death moving among the bodies. I thought he was going to come for me next, but then it turned and ran away.” (GM Note: Urstul doesn’t actually believe it was an “angel of death”, but he wants to present himself as a confused rube who just happened to be passing by.)

Note: Urstul also has a black flying snake tattoo, but his is located on his left breast and is not visible unless the PCs somehow (and for some reason) strip him down.

THE WATCH ARRIVES: See Dragon Heist, p. 44-45.

DESIGN NOTES

The witness list has been expanded here specifically to reincorporate NPCs the characters may have been interacting with during Chapter 2. Accent the list with any other familiar faces the PCs might recognize, although not everyone in the area should be someone the PCs know.

Note that the in the published version of the campaign Urstul is the one to steal the Stone of Golorr from Dalakhar’s corpse, but in this continuity the nimblewright steals the Stone (and it’s the nimblewright’s trail the PCs will be following). This also means Urstul can still be onsite, allowing the PCs to encounter him face-to-face before interacting with him at the Gralhund Villa.

PHASE 2: ON THE MATTER OF NIMBLEWRIGHTS

Once the PCs have the description of the mechanical man responsible for the attack, the next step is to figure out exactly what it was and where it came from.

RESEARCH: A DC 13 Intelligence (Arcana) can reveal that it was a nimblewright, most likely built by the technomancers of Luskan and based on ancient Calishite designs of the Shoon  Imperium. They had not previously been seen in Waterdeep and the Luskan technomancers have been reticent about sharing their secrets. If they succeed at DC 17, however, they learn that Bowgentra Summertaen, Lady Master of the Watchful Order of Magists and Protectors, is known to have recently come into possession of one.

Imperium. They had not previously been seen in Waterdeep and the Luskan technomancers have been reticent about sharing their secrets. If they succeed at DC 17, however, they learn that Bowgentra Summertaen, Lady Master of the Watchful Order of Magists and Protectors, is known to have recently come into possession of one.

Following up on the Luskan angle is possible, with a DC 17 Charisma (Investigation) check revealing that the Sea Maidens Faire carnival ships recently came to Waterdeep from Luskan and the performers might know more.

CANVASSING: A DC 13 Charisma (Investigation) check reveals two owners of nimblewrights (see below). For every two points of margin of success, they discover an additional owner.

OTHER APPROACHES: Perhaps the PCs approach their faction for information on the mechanical man. Or they could easily come up with some completely unanticipated idea. If the approach seems plausible, default towards providing them 1-2 nimblewright owners.

THE BONUS CLUE: The bonus clue, described above, will also point the PCs towards one of the nimblewright owners (the Temple of Gond).

DESIGN NOTE

The PCs aren’t meant to find all the owners of nimblewrights here. The intention is for them to trace the nimblewrights to Jarlaxle. If they do so and then steal Jarlaxle’s records of sale, they’ll find a list of all the owners, including those on the list below that they didn’t already identify + the Gralhunds.

(This path is actually more difficult than just asking “Captain Zord” for help – because the PCs have to (a) steal the records and then (b) investigate all the different buyers before identifying the Gralhunds. But it has the advantage of not tipping off Jarlaxle, possibly eliminating an entire faction from the Grand Game.)

The bonus clue will preferentially point the PCs towards the fully developed Temple of Gond from the published scenario. If you want to open things up a bit, give the PCs two owners via the bonus clue. For example: “I think I saw a similar automaton in the Twin Parades yesterday. He was part of the Temple of Gond’s procession.” And then a bystander pipes up, “Hey! You’re right! I’ve seen something like it before, too! It was dueling down at the City Armory!” Or whatever owner you want to evoke.

OWNERS OF THE NIMBLEWRIGHTS

Jarlaxle has sold 9 nimblewrights. His asking price is just 25,000 gold dragons – which is a lot of money, but shockingly cheap as far as constructs go. That’s because he’s selling them at loss. His interest is not in making a profit from selling mechanical constructs: The nimblewrights have clairvoyance crystals built into them, allowing Jarlaxle to use a special crystal ball to capture “records of witness” through the eyes of each nimblewright, which he can review at his leisure. (See “Nimblewright Crystal Ball”, below.) He simply wants to get nimblewrights positioned in as many advantageous households and organizations as possible, collecting intelligence and blackmail opportunities.

TEMPLE OF GOND: The House of the Inspired Hands is described on p. 46 of Dragon Heist. The nimblewright they’ve named Nim has, much to their surprise, proven remarkably adept at interacting with and even creating their mechanical marvels. (He does not, however, have a nimblewright detector.)

- Appearance: Its “hair” consists of multi-layered, overlapping metal feathers.

BOWGENTRA SUMMERTAEN: Lady Master of the Watchful Order of Magists and Protectors, a guild for wizards and sorcerers in Waterdeep. Her nimblewright is serving as a majordomo-cum-curiosity piece at the Order’s guildhouse.

- Appearance: The nimblewright’s head is is featureless – no eyes, no mouth, no nose, no ears, no hair. (This does not impede its senses of sight or hearing.)

LORD LABDAR ADARBRENT: Head of a noble Waterdhavian family who owns the fourth-largest shipping fleet in the city and has strong ties with the Master Mariners’ Guild. His nimblewright stands as a guard in his front hall, replacing the human guard who once stood there.

- Appearance: Its eyes are black onyx and its face is fixed in a permanent, rictused scowl. It wears the tabard of House Adarbrent.

LORD CORIN DEZLENTYR: The wizened, half-elven head of the Dezlentyr family. They first rose to prominence in the 13th century as caravan masters, traders, and explorers. They own a villa in the Sea Ward ($51 on the 3rd Edition City of Splendors map). The nimblewright was actually purchased by his headstrong, swashbuckling daughter, Hermione Dezlentyr.

- Appearance: Its right eye is a green gemstone which glows faintly. Hermione has dressed it in traditional swashbuckling gear – the hate, the doublet, and so forth. (This lends it an appearance quite similar to the Gralhunds’ nimblewright, although it lacks the Van Dyke beard.)

HOUSE OF WONDER (TEMPLE OF MYSTRA): Jarlaxle may have gotten a little cocky here. The servants of Mystra obtained the nimblewright in the hope of unraveling the secrets of its construction. They have not done so (at least not yet), but they did discover the clairvoyance crystal and have successfully removed it from their nimblewright. (If you want to complicate things, send a Bregan D’Aerthe response team to reclaim the compromised nimblewright from the House of Wonder.)

- Appearance: Feminine in appearance, dressed in a simple white robe. Silver “hair” has been carved to resemble a bob cut.

MOTHER TAMRA’S HOUSE OF GRACES: A finishing school catering to young ladies of ambitious families located on Mendever Stret in the Castle Ward. Their nimblewright is serving as a housecleaner.

- Appearance: Eight halos of different precious metals circle the nimblewright’s head at strange, intersecting angles.

CITY ARMORY: Located in the Sea Ward ($75 on the 3rd Edition City of Splendors map), the members of the Armory Guard have a nimblewright who serves as a fencing partner. They appropriated the funds to purchase the nimblewright without really having proper authorization.

- Appearance: Simple, generic facial features, but this nimblewright has additional plates of gleaming metal positioned around its body to resemble a stylized breastplate and greaves.

THE GRALHUNDS: The guilty party.

FACTION MEMBER: A prominent member of one of the factions the PCs belong to. Possibly their direct contact, but it’s arguably more effective to have it be someone they’re not personally acquainted with yet: It will make the outcomes of the investigation less certain, raise more questions in their mind, and have wider-ranging consequences in terms of deepening (or radically changing) their relationship with the faction.

INVESTIGATING THE OWNERS

As the PCs track down and question the owners, their stories and interactions will all be different, but make sure to establish the key revelations:

CORE REVELATION: The nimblewrights were all purchased from Captain Zord of the Sea Maidens Faire. His carnival ships are currently docked at a rented pier.

SECONDARY REVELATION: Captain Zord is selling the nimblewrights for a shockingly low price.

NIMBLEWRIGHT APPEARANCE: It’s important to note during these visits that the nimblewrights all look different from each other. While they share certain key features (a slight, nimble build; construction from thin, curved plates of burnished metal and pale wood; their visible clockwork mechanisms), each is a bespoke creation with distinct, unique features. If you slip up and describe the nimblewrights as all being identical to each other (and, particularly, identical to the Gralhunds’ nimblewright), the PCs will have no way of figuring out who the guilty nimblewright belongs to and their investigation is likely to turn into a muddle.

THE JARLAXLE CONNECTION

Once the PCs have tracked the nimblewrights back to “Captain Zord”, there’s generally three directions their investigation can take.

TALKING TO ZORD: If the PCs simply seek a meeting with Captain Zord, it’s relatively easy to obtain. If they ask him about the ownership of a particular nimblewright, he’ll first want to know why they’re looking for it. His curiosity satisfied, he’ll excuse himself for a few minutes, and then return to tell them that the nimblewright they’re looking for was purchased by the Gralhunds. He can even give them an address.

TALKING TO ZORD: If the PCs simply seek a meeting with Captain Zord, it’s relatively easy to obtain. If they ask him about the ownership of a particular nimblewright, he’ll first want to know why they’re looking for it. His curiosity satisfied, he’ll excuse himself for a few minutes, and then return to tell them that the nimblewright they’re looking for was purchased by the Gralhunds. He can even give them an address.

Easy-peasy. (Except for the part where they’ve inadvertently tipped off Jarlaxle and brought him into the Grand Game.)

ZORD’S RECORDS OF SALE: If the PCs stage a heist to steal Zord’s records of sale, they’ll find the Ledger of Nimblewright Sales in Area J30 of the Eyecatcher (see Part 4B). This ledger records all the current owners of nimblewrights in Waterdeep.

THE CRYSTAL BALL: If the PCs discover the existence of the nimblewright crystal ball (see below), this can be found in Area U4 of the Scarlet Marpenoth (see Part 4B). If PCs stage a heist to access or steal the crystal ball, they can review the records of witness and easily discover that the nimblewright responsible for the fireball was sent by the Gralhunds.

THE NIMBLEWRIGHT CRYSTAL BALL

The nimblewright crystal ball is actually a rare and incredibly powerful crystalmantic artifact that’s not inherently associated with the nimblewrights: It is attuned to specially created clairvoyant crystals, and is capable of not only perpetually scrying through those crystals, but also creating and storing records of witness. Basically, it allows you to not only view “live feeds” from any attuned clairvoyant crystals, you can also review everything those crystals have “seen” in the past.

Jarlaxle and his agents killed the dragoness Asphosis and stole the crystal ball from her horde. The technomancers of Luskan have been creating attuned clairvoyance crystals and building them into the nimblewrights. Thus, the crystal ball is currently capable of seeing out through the eyes of any nimblewright.

STUDYING THE NIMBLEWRIGHTS: The clairvoyance crystals are very carefully hidden deep inside the nimblewrights’ clockworks (and, at least initially, appear to be an integrated part of their operation; they’re not just wedged in there randomly). If several hours can be taken to carefully study a nimblewright (including at least partially disassembling it), a DC 18 Intelligence (Arcana) check will discover the crystal’s superfluous nature and then normal efforts can be used to identify its function.

The attunement between crystal and crystal ball can be traced. A detect magic spell combined with a DC 15 Intelligence (Arcana) check is sufficient to identify that the crystal is attuned to something onboard the Eyecatcher (assuming the trace is followed to the harbor).

DESTROYING A CLAIRVOYANCE CRYSTAL: A clairvoyance crystal is actually quite delicate and will shatter like glass if appropriate physical force is employed.

CREATING A CLAIRVOYANCE CRYSTAL: Players who take possession of the nimblewright crystal ball have a very powerful and versatile tool. Attuned clairvoyance crystals can be scavenged from the nimblewrights (both those “in the field” and also those still located in Jarlaxle’s ships), but if they want to create more crystals, they’ll need to visit Luskan and perform a raid on the technomantic workshops there.

WHAT ELSE CAN YOU SEE? In addition to identifying the Gralhunds’ nimblewright, the PCs can access records from all of the other nimblewright owners. This is a vast body of knowledge that is either banal or essential.

You might even include older records of witness from before the time that Aphosis took possession of the ball. These might be fragmentary and incomplete, but their study could reveal any number of adventure seeds for the PCs.

Perhaps there’s even a very old crystal that remains attuned to the crystal ball and located somewhere within Undermountain.