Something to consider when it comes to declaring intention is the difference between a mechanics-first declaration and a fiction-first declaration.

A fiction-first declaration describes the intention in terms of the game world. After the fiction-first declaration has been made, a decision will be made (probably by the GM) about how to model that declaration mechanically. For example:

GM: The courtyard is filled with guards.

Player: Can I sneak around the perimeter of the courtyard? Stick to the shadows?

GM: Yes. Give me a Stealth check.

A mechanics-first declaration, on the other hand, states the mechanic the player wants to use. For example:

GM: The courtyard is filled with guards.

Player: Can I make a Stealth check to get past them?

GM: Yes. [after the check] You sneak around the perimeter of the courtyard, sticking to the shadows.

In my experience, a mechanics-first declaration usually results in the GM providing the fictional description (usually as part of the narration of outcome after the check has been resolved), but this isn’t always the case. You could just as easily see:

GM: The courtyard is filled with guards.

Player: Can I make a Stealth check to get past them? Maybe sneak around the perimeter of the courtyard?

GM: Sure. There are a lot of shadows. Give me the check.

If you’re still not clear on the distinction being drawn here, imagine a player who does not know the rules declaring actions for their character: They just tell the GM what they want their character to do and then the GM figures out what mechanic to use. Their declarations are, by necessity, fiction-first declarations.

Conversely, consider someone using a dissociated mechanic. For example, someone spending a Luck Point to re-roll a die. Their character doesn’t know what a Luck Point is, so the decision to use the Luck Point or not is, by necessity, purely mechanical and any declaration to use a Luck Point is automatically a mechanics-first declaration.

(One of the major disadvantages of dissociated mechanics is that they prevent or disadvantage fiction-first declarations. And their mechanics-first declarations aren’t roleplaying.)

Those distinctions are really clear, but the difference between fiction-first and mechanics-first declarations can get pretty muddy in practice. Generally speaking, the less abstract the mechanic is the muddier the distinction becomes. For example, when you say, “I attack him with my sword!” in most systems, you are making a statement which is simultaneously mechanical and fictional.

Things can also get muddy if the player is making their own fictional description of a mechanics-first declaration, but semantically swaps the verbal expression of their decision-making process. For example, this:

Player: I’m going to sneak around the perimeter of the courtyard and make a Stealth check to get past them.

Looks superficially like a fiction-first declaration because the “fiction bit” came first in the sentence. But, functionally speaking, it’s identical to:

Player: I’m going to make a Stealth check to get past them by sneaking around the perimeter of the courtyard.

That player is making a mechanical choice and declaring their intention to use that specific mechanic. (This is not to say, however, that a player can never make a fiction-first declaration and then be the person to suggest the appropriate mechanic to model that action. That’s why the distinction can get pretty muddy.)

ONE TRUE WAY

So which of these is the “wrong” way to do it?

Neither.

Occasionally you’ll get purists who think one approach or the other is the one-true-way of roleplaying games: The fiction-first purists will generally talk about how it’s more immersive or how a mechanics-first approach “isn’t really roleplaying”. The mechanics-first purists will talk about how a simple mechanical declaration is concise and clearer or get upset that the fiction-first purists have “forgotten the game part of roleplaying game”.

But while personal taste (of both the group and the individual players) will obviously have an impact on how intentions are declared at the table, the reality is that pretty much any game being played in the real world is going to see a mixture of fiction-first and mechanics-first declarations. It’s a pain in the ass to spend every single round trying to figure out whether the description of a particular sword thrust is a full attack, a standard action, or fighting defensively. And a roleplaying game that consisted of nothing except purely mechanical interactions would be bland as hell.

As for the claim that mechanics-first declarations aren’t “real” roleplaying, fuhgeddaboutit: With the exception of occasional dissociated mechanics like Luck Points or GM Intrusions, the mechanical decisions in a roleplaying game ARE roleplaying decisions. And if by “roleplaying” you just mean “speaking immersively and/or in character”, it’s also notable that mechanics-first approaches are also a prerequisite for fortune-at-the-beginning resolution techniques, which are frequently employed in order to create rich, challenging roleplaying-as-acting opportunities. (We’ll come back to that.)

As a final note, most of the problems I see people associate with mechanics-first declarations are actually the result of a missing method: If someone says, “I want to use Diplomacy to talk to Lady Veronica,” the problem isn’t that they invoked the name of a specific skill; it’s that they’ve failed to explain how they’re using it. Similarly, if someone says, “I want to attack the orc,” the correct response is, “What are you attacking with?”

MECHANICS-ONLY

The terms “mechanics-first” and “fiction-first” both inherently imply that the other half of the equation is following in the footsteps of the first: You do mechanics first, then fiction. You do fiction-first, then mechanics. You take the mechanical model of the game world and you describe what the model tells you happens in that game world. Or you describe what’s happening in the game world and you model that mechanically. It’s a linked cycle.

Because it is part of this linked cycle, the mechanics-first approach should not be mistaken for another style of play which I’m going to call mechanics-only. In the mechanics-only approach, the link between the mechanics and the description of the game world is broken and the course of play becomes solely determined by the mechanics.

In reading that description, you may be thinking of something like this:

Player: I attack the orc. 22 to hit.

GM: You hit.

Player: 18 points of damage.

GM: The orc swings at you. Give me a defense roll.

Player: 12.

GM: The orc misses.

But while that might be an example of mechanics-only play, it isn’t necessarily so and isn’t what I’m talking about. In fact, I’ve found it quite difficult to find a way to clearly explain the mechanics-only approach in a way that people can understand it, because superficially it seems so similar to forms of play from which it is actually very, very different. This is particularly true because mechanics-only play will often feature rich and detailed descriptions of what’s happening in the game world… it’s just that those descriptions aren’t connected to the mechanics. (And it’s intriguing to note that the people who seem to struggle the most in understanding the distinction are the people actually engaged in mechanics-only play, largely because they don’t seem to realize that they’re doing something different from everyone else.)

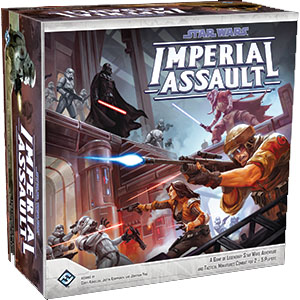

Perhaps it will be clearer if I point out that mechanics-only play frequently shows up in board games: When playing games like Arkham Horror or Imperial Assault, people will often describe narrative details or even make a point of speaking in character. But none of that material is ever fed back into the mechanics of the game; it’s merely an improvisational layer that’s separated from the game like oil is separated from water.

Perhaps it will be clearer if I point out that mechanics-only play frequently shows up in board games: When playing games like Arkham Horror or Imperial Assault, people will often describe narrative details or even make a point of speaking in character. But none of that material is ever fed back into the mechanics of the game; it’s merely an improvisational layer that’s separated from the game like oil is separated from water.

For example, consider a game of Risk. You’ve got an army in Yakutsk and you’re invading Siberia. You give a rousing speech to your troops and then describe how you divide your army in a brilliant flanking action. Then you roll the dice… and none of that has any impact on the result. And it’s not just that the game lacks a morale mechanic or that its combat mechanics are so abstract that precise troop movements aren’t mechanically modeled – it’s that the improvisation (while undoubtedly entertaining) is fundamentally divided from the actual game play. They are both happening in the same space, but there is no connection. (Or, at best, the connection is unidirectional.)

On the flip-side of the coin, in mechanics-only play you’ll see mechanical actions allowed even when the given circumstances of the fiction should disallow them.

For example, consider a roleplaying game which has a Leg Sweep combat maneuver: It’s specifically and explicitly designed to model you sweeping someone’s legs out from underneath them. Now imagine someone fighting an Undulating Hulk: It doesn’t have any legs, but for the mechanics-only players that won’t matter. Nothing in the rules say you can’t use the Leg Sweep maneuver on the Undulating Hulk, so you can do so.

Maybe you’re thinking that this is just an example of the GM deciding that a particular mechanic (the Leg Sweep) is close enough to whatever effect the PC wants to have on the Undulating Hulk (delaying them for a Minor Action or whatever) so that they can use it as the basis for adjudicating the action. But that’s not what’s happening in mechanics-only play.

Imagine a spell that stops the target’s heart from beating and, thus, kills the target. Unless the explicit mechanics of that spell limited its potential target list, the mechanics-only player will allow it to be cast on a vampire, even though their heart is no longer beating in the first place. They’ll even allow it to be cast on an animated skeleton, despite the fact that the skeleton has no heart to be affected by the spell.

I generally try to avoid making one-true-way statements about how games are supposed to be played. The medium of roleplaying games is pretty flexible and, historically speaking, the best and most successful games have been those which have allowed multiple styles of play to come together at the same table (which is a testament to the breadth of experience that RPGs can provide). But when it comes to mechanics-only play, I’m comfortable saying that you are doing it wrong.

The net effect of mechanics-only play, when applied to a roleplaying game, is to needlessly turn associated mechanics into dissociated mechanics. As I’ve noted in the past, I don’t have an automatic objection to dissociated mechanics existing in an RPG, but those mechanics should bring some distinct benefit that would otherwise not be achievable. The mechanics-only approach has no discernible benefit. It’s not so much that you’re tossing the baby out with the bathwater, you’re just tossing the baby out.

It’s hard to say exactly how prevalent the mechanics-only style of play is. I haven’t encountered it much “in the wild”, so to speak, but online discussions of dissociated mechanics often attract these players. (Because mechanics-only players turn associated mechanics into dissociated mechanics, they can’t really comprehend how anyone else can see a distinction between them.)

I do have a sense that mechanics-only play may crop up more frequently in combat, even among players who don’t otherwise engage in it. This may even be a significant contribution to the common belief that there’s some sort of division between “combat” and “roleplaying”. (Which I’ve always had difficulty grokking, because life-or-death stakes should be a crucible of character development. It shouldn’t be a place where characters get turned off.)

(What about fiction-only? That’s playing “let’s pretend” without any mechanical structure. It tends not to crop up in roleplaying games because it inherently doesn’t require the game, although you can see certain tendencies towards it in certain types of dice-fudging or groups that simply ignore certain types of mechanics.)

Just a meta-comment. I stumbled on your blog just a few days ago and having chewed through a good bit of it, I’m super-pleased with what you’re offering. As I slowly get spun-up on reviving my old AD&D habits, it’s been a good source of inspiration for me. Thanks and keep it up!

A less extreme (but probably more common) variant of the “mechanics-only” playstyle is something we could call “mechanics-priority”, where most (or even any) situation is resolved through a careful reading of the rules (“legalistic” is probably a better name), and that it always trump a more “commonsensical” or “fiction-sensical” interpretation; in other words, the criterion is always the letter of the rules, never the spirit. So if the “leg sweep” rule does not specify that this maneuver works only when the enemy stands on some kind of appendages, the interpretation would be that leg sweep is a fair move. If the rule specified that the leg sweep is possible only if the target stands on feet, a legalistic reading would say that a monster standing on tentacles cannot be targeted by this maneuver.

In a sense, some rules in mechanics-heavy games kind of need the players to accept them even if they do not seem to make much sense (at least, not always). As an example, the “hide in plain sight” ability in D&D 3.5 (I think it was a Ranger ability) eventually let a PC just nonmagically “vanish” in front of people. Another is the “coup de grâce”, where one would need to stab a totally immobile and helpless enemy in the throat many times to kill them. I started to have a lot more fun playing D&D once I decided to stop trying to make sense of a lot of rules and just accepted to play with them. Playing Risk is more fun if you don’t try to understand why surrounding you enemy does not gives you an edge and play the games as it’s meant to be played instead (unless we start to homerule the game, but that’s beside the point.)

Moreover, some rules are “arbitrarily” specific, probably for the sole reason to balance the game. One clear example of this is a Nano esotery in Numenera; I can’t recall the name, but this power let the PC resist any hostile environment, letting them swim in burning lava or survive in a world with 50G gravity. The description specify that this power does not let the PC resist damage from attacks; so swimming in lava is fine, but not a fireball; 50G gravity is fine, but not a constrictor snake.

I’m not saying it’s a good or a bad way to play, but these kind of rules kind of encourage a “legalistic” playstyle.

Great post, I’ve been chewing on this exact idea myself, but from a slightly different angle, mostly inspired by experiences with Mouse Guard.

In the interplay between mechanics and fiction, I’m interested in individual decision-making processes and utterances. For example, here’s one breakdown of play from a hypothetical fight (I’ll number them for their order)

1. player describing their character’s intent (e.g. “I attack the orc”)

2. GM clarifying intent (e.g. “How?” “I run across the ice and hit him with my mattock!”)

3. selecting a corresponding mechanic (e.g. “Okay, that’s a to-hit roll.”)

4. quantifying the fictional state (e.g. “..and you’re on ice, so that’s going to be a -2”)

5. mechanical resolution (e.g. “I rolled a 17. Yes! And 7 points of damage.”)

6. fictionalizing quantities/describing mechanical outcomes (e.g. “Awesome, you chop off the orc’s arm and he goes down like a sack of rocks.”)

Boardgame play often consists of just 3. and 5. There’s no fictional state to quantify, and it’s not necessary to produce any. You can, but it’s only decorative, because the mechanics make it clear that the quantities are a sufficient representation of the game’s state, and there are no inlets for fiction anyways.

Mouse Guard’s detailed Conflict system is a little board-gamey because a) step 3, choosing a mechanic, happens first, and b) there are no rules for quantifying fiction mechanically (i.e. there are no modifiers for doing things quickly, carelessly, or coming up with a good idea for a tactical advantage). (Interestingly, its regular resolution mechanic is expressly not like this.)

But even when fictional state /could/ have an effect, I find some systems do tend to produce board-gamey play – the recipe seems to be a) when the mechanics resolve situations at more or less the same granularity at which the participants want to talk about then, and b) the quantities and mechanics are sufficiently detailed that they form a sufficient representation of game state.

For example, in D&D 3e combat, there are so many rules, governing nearly every aspect of contentious situations that you could play mechanically and not feel like you missed any important events – and there are already so many modifiers encoded in the rules that actually using all of the relevant rules displaces some appetite for introducing a steady stream of modifiers.

You can play a long D&D fight and not really notice that none of the purely fictional utterances contributed to resolution at all, because the mechanics are doing a decent job for representing most of the state we’d care about, tactically.

Also, in some games you get sequences like 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 – with no fictionalization of the mechanical outcomes. (e.g. You run across the ice to hit the orc with your mattock and do 7hp damage.)

There are also hybrid mechanics that make it hard to classify as either entirely fiction-first or mechanics-first – take Volley in Dungeon World. The player expresses a fictional intent, there’s a choice of resolution mechanic (the ‘Volley’ move), then resolution starts. On a 7-9, however, there’s an additional step where the player has to make a mechanics-first choice (they have three choices), and only then is outcome of resolution given a fictional characterization.

“fortune-at-the-beginning resolution techniques”

I’m not familiar with that term. Can you spell out what you mean by it?

@andrewsw: Thanks! Glad you’re finding useful stuff here! And I’m always excited to hear people getting back in the RPG habit!

@Wyvern: There’s a much longer post about fortune positioning coming up, but here’s the short version.

Ron Edwards coined the terms “fortune-in-the-middle” and “fortune-at-the-end”. He later mucked them up pretty badly, but if you look at his original (and actually useful) definitions of the terms, fortune-at-the-end mechanics have you establish your method and then you turn it over to the mechanics and the mechanics tell you what happened.

Fortune-in-the-middle mechanics create an additional decision point in the middle of resolution. Michael offers a hard-coded example of that with Volley in the comment immediately above yours. This can also happen on-the-fly with things like partial success or partial failure: You make a Jump check and miss it by 2 points, so the GM says “you come up short, barely grabbing the ledge on the side of the crevasse; your legs are dangling over the abyss, what do you do?”. (There are other varieties of this, too, but that’s the basic idea.)

Edwards later mucked these terms up by trying to separate them from mechanical resolution (even though the fact that they’re about mechanical resolution — i.e., fortune — is literally in the name of the damn term). At this same time he claimed that fortune-at-the-beginning doesn’t exist. He’s wrong. Fortune-at-the-beginning is a technique where you ask the mechanics what happens and then you use the mechanical result to describe what you attempt.

This often means that fortune-at-the-beginning occurs between intention and method. It’s a rare technique, and it seems to be used for best effect in social interactions: You state your intention (“I want to convince the Duke to give us troops”), then you’ll make a Diplomacy check (or whatever), and you’ll use the outcome of the Diplomacy check to inform how you roleplay the scene.

Similarly, personality mechanics often use this: You make a madness check or you make a check to see if you can resist temptation, and if you can’t that determines how you play the next action.

I also occasionally see people do things like making an Intelligence check to see if their character is smart enough to think of the idea they just had. Over the years I’ve had a couple of players in old-school D&D systems who would make Charisma checks to see how they would roleplay the next scene.

Michael, I’m not sure I follow what you’re trying to say in the second half of your post (especially the paragraph starting with “But even when…”).

You seem to be suggesting that D&D3e encourages “board-gamey” (i.e. mechanics-only) play because it has specific rules for every contingency the designers could think of. But I don’t see how that differs from what you described as “quantifying the fictional state” in your earlier example: you get a -2 to attack rolls while moving on ice. What difference does it make whether the penalty was spelled out in the rules or the GM made it up on the spot? It sounds a bit like the false dichotomy of “rules vs. rulings” that Justin picked apart in another article, although I don’t get the impression that’s what you intended to suggest.

Wouldn’t it be more accurate to say that detailed rules systems make it more difficult to *distinguish* between mechanics-only play and mechanics-plus-fiction play, rather than actually favoring the former? The way they do this is by closing the loopholes that would make it obvious when you’re playing in a mechanics-only fashion. (For instance, if the rules explicitly state that Stop Heart doesn’t work on undead or constructs, a mechanics-only player isn’t going to attempt to use it on a skeleton.)

@ Justin: Okay, that makes sense. Not speaking from personal experience, since I haven’t played any of them myself, but aren’t fortune-at-the-beginning mechanics rather common in storytelling games? I’m thinking of the sort of mechanic where you roll dice or whatever to determine the outcome of a “scene”, and then someone (usually whichever player won narrative control) describes how the scene plays out based on the result of the mechanical resolution.

I would say that 4e combat was far more mechanics-only than 3e. The 4e rules even explicitly stated that the flavor text and name of a maneuver/power had *no effect* on whether or not you could use it on a particular opponent – you were encouraged to change description on the fly if necessary, but often this meant players simply ignored any kind of narrative description during combat.

Personally, I don’t have undying faith in players’ (or the GM’s) willingness to accompany all their mechanical checks with engaging fiction.

I’ve witnessed it on a number of occasions when people seemed to intuitively accept that the only appropriate method of play is mechanics-first + optionally describing the result in fictional terms, the latter mumbled awkwardly more often than not. Obviously, my experience isn’t universally indicative, but I’ve seen that sort of complaint in a number of places. Roleplaying is somehow approached like boardgaming + narration, possibly because people aren’t really wired for the “get into character, engage with the fiction from inside” task of roleplaying.

Now, what I’m thinking, spurred by your Undulating Hulk/Vampire example, is what if the game, mechanically speaking, simply couldn’t proceed if the fiction isn’t sufficiently well-established before the dice are thrown (irrespective of whether it’s fortune-at-the-end or in-the-middle)? What if the players need the GM to establish the scene well enough so they can choose the proper mechanics to engage?

I mean, yeah, you describe the guards and the players automatically decide “Combat/Stealth/Diplomacy”, but what if the rules reward describing stuff at a higher/more interesting level of detail, with a corresponding set of finer-grained choices that the players can make to affect the scene?

And the opposite, and maybe more important: what if the GM could mechanically influence the scene, hanging an interesting consequence or complication from a narrative detail that a player supplies? In mechanics-first plays you decide to use Diplomacy, but what if that “Diplomacy” is actually narrated as a subtle, casual threat, detectable only by the target? And what if the rules offer the GM a choice to either fit the consequences into a Diplomacy “table” of resolutions, or an Intimidation one? Then the GM, I imagine, would want to know what they can play with, so they’d have to ask the players for more details in the fiction. (Now did you mean to actually threaten that guy of butter him up? How exactly do you do it?)

This isn’t unimportant to pure combat, I’d imagine, as well. Conscientious fictional positioning before the start of a battle could make things easier and tactically more interesting when the time comes to roll the dice. (“Yeah, while he threatens the shopkeeper, I sneak a peek outside the shop to see if anyone would make a fuss should things turn violent.”)

@Wyvern I’ll see if I can clarify what I meant.

Let me back up and say that I think Justin’s terms of “fiction first”, “mechanics first” are a great way of starting the conversation, but I don’t see them as elemental or fundamental.

Justin’s own example of the orc attack has no fictional content, so it’s meaningless to try to classify it as being either mechanics-only or mechanics-first. These styles may be very different in other situations, but not in this case. (Just like it’s meaningless to argue about whether a solid blue painting is “really” blue-only or more-blue-than-red. It’s both. The solid blue painting illustrates that these labels we’re coming up with don’t tell the whole story.)

You ask, “What difference does it make whether the penalty was spelled out in the rules or the GM made it up on the spot?” and.. good question, I don’t think I was saying anything about that.

By “quantifying fictional state” what I’m getting at is when the GM takes something that doesn’t have a mechanical representation (e.g. ‘the floor is a bit icy’), weighs it, and assigns it a mechanical significance (e.g. -2). This is one way for fiction to have significance.

I’m contrasting with things like Maneuver in Mouse Guard or D&D 3e attacks of opportunity which only have mechanical inputs. Nothing in Mouse Guard suggests the GM ought to give PCs an advantage to maneuver if they’ve got a tactical advantage; nothing in D&D 3e suggests the GM should be thinking about whether the AOO player is maybe a bit too sleepy to react.

So, these particular mechanics tend to sideline the established fiction. If you have enough mechanics like this jammed together into a subsystem, it tends to sideline the fiction for large parts of gameplay. You /can/ describe all of your attacks, or how alert your character is, but you don’t need to (except for its inherent entertainment value) because none of it affects what happens. The mechanics are a closed system. I think of this as 3, 5, 6 play. (Select mechanic, resolve mechanic, describe mechanical outcomes.)

You ask, “What difference does it make whether the penalty was spelled out in the rules or the GM made it up on the spot?” Good question. (I don’t think I was saying anything about this in particular.)

If there’s a to-hit modifiers play chart has a few entries, one of them being “-1 to -4 – minor to serious disadvantages”, then that’s an encouragement to the players and GM to produce and consider ways to fictionally disadvantage their opponents. That’s one way that a game can make room for the fiction, slanting resolution toward 1,3,4,5,6 and not just 3,5,6.

Going to take a slightly different tack here – I think your “luck point” complaint is a little bit offbase. Or rather, that it’s a bad example of the disadvantage of a dissociated mechanic.

A luck point for a re-roll necessarily happens during a mechanics only phase ANYWAY. If we use Michael’s chart from up about, the “I use a luck point” decision is basically happening during stage 5 – the same as like, doing the math on your die roll, and picking up another die for damage or whatever. There’s no roleplaying here because this is a strict ‘resolution’ phase. The Luck Point or whatever is just another ‘modifier’ on the die roll like +2 for flanking or +5 for “divine favor” or whatever. Just because the player decides to use the luck point after the first die roll rather than before doesn’t mean the mechanic is any more or less ‘just mechanics’; This whole step is ‘just mechanics’. All you do here is tabulate your modifiers, roll a die, add up some numbers, and compare it to a target number. No roleplaying ever occurs during this step.

So in this particular case, the objection of that dissociated rules are “purely mechanical and any declaration to use a Luck Point is automatically a mechanics-first declaration.” is… moot. Because it is happening during a part of the game where only mechanical things happen. Perhaps you find it undesirable that there should be decisions made at this point, though I think that is separate from associated/dissociated mechanics, because it is easy enough to imagine associated mechanics that add a decision in this area – such as any sort of magic weapon power that can be ‘activated’ on a hit to deal extra damage.

@Emanuil: You can’t “solve” mechanics-first declarations by creating more mechanical categories. If you create a mechanical distinction between “stealthy Diplomacy” and “open Diplomacy”, that still won’t prevent someone from declaring that they want to use the stealthy Diplomacy mechanics.

Generally speaking, the only way you can “force” fiction-first declarations is for the GM to set their threshold for method at a point of fidelity beyond whatever mechanics they’re using. IOW, any time somebody makes a mechanics-first declaration the GM asks, “How are you doing that?” until they get an answer that isn’t an explicit mechanic. (e.g., “I attack the orc” “how are you doing that?” “I carefully approach, testing its defenses”) Ironically, the more detailed and finely-grained you make the system, the harder it would be to actually push through to fiction-first approaches. (e.g. “I attack the orc” “how are you doing that?” “I fight defensively” “how are you doing that?” “I carefully approach, testing its defenses”)

Having said that: Check out Technoir. The core mechanic of Technoir involves using Verbs to push adjectives onto your target. (A character’s Verbs basically work like skills.) The adjectives have a mechanical impact, but it’s not specific. That means you necessarily have to think about the effect you want to have in the Fiction.

(This can still result in mechanics-first declarations: “I use Hack to push Exploited on him.” But, in general, the system is still encouraging a more specific focus on the fiction.)

Actually, I wasn’t thinking about creating more mechanical categories, but of mechanical rulings that take place within a more detailed fictional context. So it’s not going to be stealthy diplomacy against open diplomacy, but an effect that takes place each time you play rough with someone, which could happen in a number of contexts not bound by utilizing specific skills but by utilizing a specific narration. And a GM response could be:

“Okay, so from what you’ve told me you seem to qualify for a “playing rough” roll/bonus/penalty/etc. Is that right?”

And in turn different descriptions of playing rough could carry some descriptory tags (playing rough with a serene smile probably qualifies for some sort of “psycho” custom effect) that could activate some more of that sort of adjudication.

My main point was that a system, and Technoir is an excellent example now that I look at it, should make narration necessary not by admonition, but by being designed in such a way that either the GM or the players wouldn’t know what to say next if they don’t hear a decent grounding piece of narration before that. (For instance the GM in Technoir wouldn’t know what actions to counter with or what other tactical variables to include if they didn’t get a decent impression of how the player has used their own verbs, not of just which one they chose, and also what sort of nuance they’re going for with a particular adjective.)

Emanuil, most PTBA moves are designed to have players speak in the fiction rather than with the mechanics.

However, as John Harper commented, the crux of the issue is how do you achieve a balance between satisfyingly exploration of the fictional space, and moving the game and conflicts forward.

I don’t see why some comments here assume that by making mechanic-based decisions you are not roleplaying. To roleplay is to make decisions as if you were the character, not to ACT or to speak in character, that’s theater. To choose a high ground because it gives you a bonus to attack and defend is to engage the fictional world as your character. “Don’t try it Anakin, I have a higher ground”(Obi Wan). Sure, players aren’t professional actors so they would just go for “I jump over that stone to take a high ground bonus”, that’s bad acting but good roleplaying.

The difference between Luck Points/Fate Points, etc. is that the player is taking decisions that the character is not aware of. “Now I have only 1 Luck Point left, I better be more careful” That’s a player decision, but not a character decision, so it’s not roleplaying.

“For example, consider a game of Risk. You’ve got an army in Yakutsk and you’re invading Siberia. You give a rousing speech to your troops and then describe how you divide your army in a brilliant flanking action. Then you roll the dice… and none of that has any impact on the result.”

I have read this quite a few times and still don’t know whether I agree with the idea Mr.Alexander is trying to present here or not. I have to agree with Charlie’s comment and have to question what you mean? Since I am unclear as to whether or not it’s agreeable, perhaps points could be clarified?

Now, I’ve read a bunch of stuff from a bunch of people on role playing games online, and some of it actually had to do with circumstances that look similar to what I quoted above. “If a person makes a rousing speech for a persuasion roll, we should give them a bonus or just automatic success simply because of the quality of the speech.” Or similar arguments.

Now let’s be clear on my stance, I’m going to try to present an open mind here. Curious and willing to discuss rather than presenting my own opinion. Maybe opposing advocate or something.

But I find it hard to disagree with the people who say it isn’t correct to allow that kind of happening, because it’s “playing the gm rather than playing the game”, or rather allowing “flowery” descriptions to overrule the actual statistics of the game.

If an improvised speech from a player is allowed to give a bonus to a persuadion roll, does that not diminish the value of putting skill ranks into persuasion at all? If in your previous ruling articles I allow someone to say “I use water to find the trap in the hall.” Doesn’t that imply that using water to find the trap in the hall is not already part of the “training” in trap finding skill?

On the other hand, part of my mind wants to give a reward for actions with player creativity. This is because I think it’s been sort of agreeable by a good portion of Gms that if people find a creative solution to an adventure – even if it means skipping encounters- that it is fine and it should be allowable. This seems remarkably similar to the +2 bonus, and I’m wondering if it is or not? Maybe this is completely unrelated.

I think these statements by Mr.Alexander here need a lot more explanation, at least for me.

This is of course, related to “circumstance bonuses” of +2 supposedly given by GMs willy nilly right? From the articles text I don’t know if you think I’m supposed to give +2 or advantage for “quality” descriptions or not.

I also have questions about “dissociated mechanics”. Let’s discuss this further?

@Alex: You’re kind of muddling together two completely separate thoughts, so I’m not really sure exactly what you’re asking.

As far as the “rousing speech” example is given, you should note that the next sentence makes it explicit that the impact of the speech does not necessarily need to be mechanical in nature.

An example of a non-mechanical impact could be: You want to convince Bob to do something. You might bribe him. You might threaten him. In the system you’re using, either option will be modeled as a Social skill check (so there’s no mechanical difference between the two). Nonetheless, successfully bribing Bob to do something for you would play out differently than if you threatened him to do it.

In mechanics-only play, it wouldn’t.

As far as mechanical impacts go, there is a judgment call to be made about how a player’s decision should be mechanically modeled (should “I search with water” be different than “I search”?). But that’s really a completely separate issue than what I’m talking about here.

If we were going to consider a mechanical impact, though, we could look at the bribing of Bob in the example of Bob: Should it be easier to bribe Bob with 100,000 gp than with 1 cp? Probably, right? But in mechanics-only play, the size of the bribe wouldn’t make any difference (unless there was an explicit mechanic for it).

With regards to the first example, okay then. But I still wonder about the article.

It seems that your mechanics only is not mechanics first in the way that mechanics first is similar to having the choice of bribing or intimidating or anything else. Whereas mechanics only does not allow a choice? Is that what you mean? Having a choice of what to say and how it impacts the game rather than not as in RISK?

I mean to say having the mechanics first being a choice between “I bribe with persuasion” and “I threaten with intimidate”, whereas mechanics only does not have that choice? Doesn’t RISK have a choice in which place to attack? I’ve confused myself I think.

Now for the second example, I’m not sure I get the comparison. To me right now, currency is different in a bribery example than common water is in a trap finding example. Gold would be a resource of the players that can provide a bonus as you described – 1 being different than 100,000.

But in a trap finding example, the water does not seem to be a potion of improved trap finding, it seems to be a creative improvised use of the players thoughts on the situation to solve the problem at hand. To me right now, it seems similar to saying in the bribery example that the person being bribed is thirsty…just think of using common water or beer to get him less thirsty and it’s a bonus to the roll. However, it seems that this doesnt seem to be a test of the characters but rather a test of the players. Furthermore as I said before, it is hard to imagine someone trained in persuasion that upon seeing a thirsty person is not aware enough to give them a drink.

Did you mean for the use of the water itself to be a meaningful choice somehow? To me right now, it doesn’t seem to be so, but rather a common carried object that will habitually be thrown down corridors to help checking for traps.