Technoir continues to be a big hit at my game table. It’s proven to be a success not only with my hardcore players, but also with the casual brigade. The question now is whether it can be bootstrapped into either an open table of some sort or settle down into a dedicated group. (We’ve had a few thoughts on both.)

Technoir continues to be a big hit at my game table. It’s proven to be a success not only with my hardcore players, but also with the casual brigade. The question now is whether it can be bootstrapped into either an open table of some sort or settle down into a dedicated group. (We’ve had a few thoughts on both.)

Technoir is also helping me clarify a lot of my thinking about the roles and functions of GMing.

I’ve talked in the past about the concept of “smart prep”, by which I’ve generally meant focusing your prep on stuff with high utility while avoiding prep which is either unnecessary or likely to be wasted during play. (For example, the entirety of “Don’t Prep Plots” is about focusing on smart prep.)

On that note, here are a few general principles of “smart prep”.

(1) Try to avoid prep which cuts off options during play.

Note, however, that prep inherently does this: If you decide that the walls of Castle Shard are purple during prep, then you’ve cut-off the option of making them black during play. So what you want to focus on is leaving open the meaningful options.

Another way to look at this is that you want to retain as much flexibility in what you prep as possible. This not only allows you to avoid redundant prep, it also means that you’re generally reducing your overall prep while actually increasing the utility of your prep at the same time.

For example, imagine that you’re prepping a goon squad for Baron Destraad. If you spend a lot of time figuring out exactly how to position them in Room 16B and the tactics they’ll use in Room 16B, then you’re limiting the utility of that goon squad to Room 16B. (You could, of course, simply ignore that prep. But, of course, that means you’ve wasted that prep work.)

(2) Don’t prep anything which could be just as easily generated during play.

Technically, of course, everything can be improvised during play. So what you want to focus on is the stuff that adds value by virtue of being prepped: For example, prepping stat blocks ahead of time instead of trying to generate them during play will generally speed things up at the table. Detailed floorplans or handouts can provide valuable and evocative visual aids for the players which generally can’t be created on-the-fly.

In general, look for the stuff that’s time-consuming; that requires special tools; that will benefit from considered thought; or which you know you just aren’t particularly good at winging.

(3) Try to avoid prepping any specific plots. And definitely avoid prepping any outcomes.

By which I mean stuff like “after A happens, then B will happen… unless the PCs do X, in which case C will happen instead.”

This applies at both the micro- and macro-levels. And, in many ways, it’s just a specific iteration of the first two guidelines: When you prep specific sequences of events, you’re self-evidently cutting off options (the other ways in which that sequence could play out) and prepping stuff that could be just as easily generated during play. (In fact, it would probably be easier to generate it during play since you won’t waste time with contingency planning: What happens will be what happens.)

Of course, all of these principles should be thought of as guidelines. In actual practice, there will be exceptions (often very useful exceptions). But I suggest thinking long and hard about your prep methods to see if there are ways in which you could be achieving the same results (or better results) with less prep. (Or using the same amount of prep to achieve more.) In my experience, most GMs spend a lot of time on wasted prep.

SMART PREP IN TECHNOIR

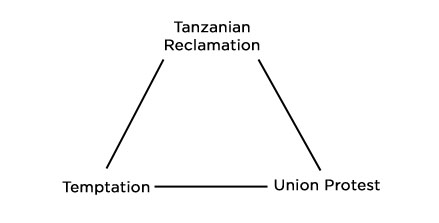

I want to take a second now to talk about how smart prep applies to Technoir, because the plot mapping scenario structure of the game ends up drawing a very clear and very specific line between smart prep and wasted prep that I think is useful in understanding the difference between the two.

As I’ve discussed before, scenario prep in Technoir takes the form of a transmission. Each transmission consists of six connections, six events, six factions, six locations, six objects, and six threats arranged onto a 6×6 master grid which allows you to randomly generate and connect these nodes to each other. The connections you generate between the nodes will spontaneously create the conspiracy-oriented scenario the PCs are engaging.

There are three transmissions included in the rulebook and you can also download the free Twin Cities Metroplex transmission. In these transmissions, each node receives a single sentence of description. For example:

Archangels of Saint Paul

A militant religious organization looking to cure the city of its sins.

Objects receive a set of tags (allowing them to act like other equipment). Connections get a full stat block (including the favors they can do for PCs). And threats get a set of 3-6 stat blocks (to be used as antagonists). But other than that, the single sentence is all you get.

Clearly there is no wasted prep here. And, speaking from experience, this minimalist approach works.

But, if we wanted to do more prep within this structure, is there value to be added? I think so. Notably, however, it would also be trivial to reduce the value of your prep even within the minimal profile presented by the sample transmissions.

Let’s start with the latter. Imagine a transmission in which we define one of the locations as:

Club Neo

A plain block of concrete glitzed in overlapping layers of multi-sensory AR.

In the same transmission we include a connection:

Madame Ling

A lady of refined manners and the drug mistress of the Lowtown party scene.

Looks good. On the other hand, imagine that we describe Madame Ling like this:

Madame Ling

The owner of Club Neo and the drug mistress of the Lowtown party scene.

Same minimalist approach, but – in the specific context of Technoir – this latter example is flawed. Why? Because it locks down the relationship between Madame Ling and Club Neo. This not only functionally “forces” Madame Ling onto the plot map if Club Neo is generated (which I’ve found can disrupt the flow and robustness of the map), it also drastically reduces the flexibility of these elements in play. (For example, without that constriction, Madame Ling could consider Club Neo a rival; she could be trying to take it over; she could be romantically entangled with the owner; and so forth. All of these options disappear if we’ve established that she’s the club’s owner.)