Twin Cities Theater Connection recently put a panel together of local artists working on summer productions of Shakespeare. You can hear the discussion on their “Summer of Shakespeare” podcast. So if you’ve always wanted to know what I sound like (and can’t afford to spring for the Call of Cthulhu audio book I did), this is your chance.

Posts tagged ‘shakespeare’

The Shakespeare Wars: Shylock vs. Godwin

I’ve recently been reading The Shakespeare Wars by Ron Rosenbaum and writing a few essays in an effort to dissect some of the irrational examples of scholastic exuberance he highlights in the book. This essay, however, changes the focus to Rosenbaum himself.

I’ve recently been reading The Shakespeare Wars by Ron Rosenbaum and writing a few essays in an effort to dissect some of the irrational examples of scholastic exuberance he highlights in the book. This essay, however, changes the focus to Rosenbaum himself.

The topic: Shylock.

Rosenbaum’s position:

It’s the most truthful and the most terrible Shylock I’ve seen. Truthful, in part, because it’s a throwback to the original, a throwback to the deeply repellent character Shakespeare created. A throwback that has no truck with contemporary cant of the sort that attempts to exculpate Shakespeare and Shylock, evade or explain away the anti-Semitism. It doesn’t fall victim to the intellectual fallacy, the comforting but deluded evasion that has pervaded many recent productions of The Merchant of Venice: the belief that if you make Shylock a nicer guy, play him with more dignity, play up the cruelty of the Christians as well, you can somehow transcend the ineradicable anti-Semitism of the caricature.

The problem with the warm and fuzzy Shylock, the feel-good Shylock you might say, is that it doesn’t diminish, it actually exacerbates, deepens the anti-Semitism of the play as a whole. The more “nice” you make the moneylender, the more you end up making the play not about the villainy of one Jew, but the villainy of all Jews, a deep-seated villainy that subsists beneath the surface even in those who appear “nice” on the surface. The more warm and fuzzy you make Shylock, the more you make it a play about the fact that even such a Jew will not hesitate, when it comes down to it, to take a knife and cut the heart out of a Christian.

The central contention of Rosenbaum’s argument is that Shylock’s final act (when he attempts to commit an act of legalized murder) is a piece of unforgivable villainy that confirms the bigotry of the anti-Semitic. Thus, the nicer you make Shylock, the worse the message becomes: No matter how nice a Jew may seem, the truth is that all Jews are murdering monsters.

THE PROBLEM

But for Rosenbaum’s thesis to stick, he has to overcome a rather sizable hurdle. In The Merchant of Venice, Shylock says:

Hath not a Jew eyes? Hath not a Jew hands, organs, dimensions, senses, affections, passions; fed with the same food, hurt with the same weapons, subject to the same diseases, heal’d by the same means, warm’d and cool’d by the same winter and summer as a Christian is? If you prick us, do we not bleed? If you tickle us, do we not laugh? If you poison us, do we not die? And if you wrong us, shall we not revenge? If we are like you in the rest, we will resemble you in that. If a Jew wrong a Christian, what is his humility? Revenge. If a Christian wrong a Jew, what should his sufferance be by Christian example? Why, revenge. The villainy you teach me, I will execute, and it shall go hard but I will better the instruction.

If you prick us, do we not bleed? This is one of the most beautiful and heart-rending evocations of the basic humanity which transcends all bigotries. And if The Merchant of Venice is, in fact, as viciously anti-Semitic as Rosenbaum claims, then it seems painfully out of place.

In short, the only way to accept an anti-Semitic reading of The Merchant of Venice is if you can explain away what may be the most eloquent skewering of anti-Semitism ever written. Rosenbaum, seeing the problem, writes:

But what about Shylock’s famous speech in his defense: “Hath not a Jew eyes? … If you prick us, do we not bleed?” one is inevitably asked. Some might argue that this indicated that Shakespeare had a more advanced consciousness than the medieval anti-Semitism that persisted into his time. Perhaps. But if the speech is read to its bitter end “do we not bleed” bleeds any poignancy dry as it turns out to be a rationale for vengefulness: If we are alike in these respects, “If you wrong us shall we [just as you] not revenge?” as well.

There are two problems with Rosenbaum’s argument.

First, he doesn’t actually explain why we should ignore the speech. He seems to be relying on an unspoken premise that “revenge is evil”. But even if we accept the premise, Rosenbaum’s conclusion doesn’t follow.

Second, Rosenbaum is setting up a false dichotomy. He’s saying “if Shylock is a villain, then the play is anti-Semitic”. Then he concludes that Shylock is a villain, ergo the play is anti-Semitic. But in setting up this dichotomy, Rosenbaum may be missing the entire point of the play.

THE POINT

When we first see Shylock and Antonio on the stage together, Shylock says:

Signior Antonio, many a time and oft

In the Rialto you have rated me

About my monies and my usances:

Still have I borne it with a patient shrug,

(For sufferance is the badge of all our Tribe.)

You call me misbeliever, cut-throated dog,

And spat upon my Jewish gaberdine,

And all for use of that which is mine own.

Well then, it now appears you need my help:

Go to then, you come to me, and you say,

“Shylock, we would have monies.” You say so;

You that did void your rheum upon my beard,

And foot me as you spurn a stranger cur

Over your threshold. Monies is your suit.

What should I say to you? Should I not say,

“Hath a dog money? Is it possible

A cur should lend three thousand ducats? Or

shall I bend low, and in a bond-mans key

With bated breath, and whispering humbleness,

Say this: “Fair sir, you spat on me on Wednesday last;

You spurn’d me such a day; another time

You call’d me dog: and for these courtesies

I’ll lend you thus much monies.”

This speech, I think, sets up the core dynamic of the play: Hatred begets hatred.

It’s not that Shylock is pretending to be a nice guy while secretly being a Jewish monster. It’s that the Christians treating him like a monster is what turns him into a monster.

Elsewhere in his book, Rosenbaum quotes a speech from the “Hand D” of Sir Thomas More that many believe may be written by Shakespeare. In reading it, I was struck by a similar theme. Thomas More is confronting a riotous, anti-immigrant crowd. As Rosenbaum writes, “the sympathy is with the immigrant-bashing nativist poor”, but then Hand D takes over. Sir Thomas More stands up before the crowd and says:

Grant them removed and grant them this your noise

Hath chid down all the majesty of England,

Imagine that you see the wretched strangers,

Their babies at their backs, with their poor luggage

Plodding to th’ ports and coasts for transportation,

And that you sit as kings in your desires,

Authority quite silenc’d by your brawl,

And you in ruff of your opinions cloth’d,

What had you got? I’ll tell you: you had taught

How insolence and strong hand should prevail,

How order should be quell’d and by this pattern

Not one of you should live an aged man,

For other ruffians, as their fancies wrought,

With self-same hand, self reasons, and self right,

Would shark on you, and men like ravenous fishes

Would feed on one another.

Again, we see this theme of hatred creating hatred; intolerance breeding intolerance.

In the end I think this is not only a more legitimate interpretation of The Merchant of Venice, I think it’s also a more interesting one.

Rosenbaum presents his opinion of Shylock within the context of a larger thesis that Shakespeare’s villains don’t need any explanation or motivation — they’re just evil. I think this is, in general, an overly-simplistic, one-size-fits-all explication of the Bard. And I think it specifically causes Rosenbaum to overlook the complexity of The Merchant of Venice.

ROSENBAUM’S DEFENSE

But if Ron Rosenbaum were reading this essay, I know what his response would be, because he trots it out a half dozen times or more in The Shakespeare Wars:

Sorry, it’s just not a character you can make nice about, or rationalize as some do, by emphasizing the play’s critique of the cruel mockery of the money-hungry Christians as well. Christians weren’t slaughtered for their religious stereotypes in Europe; Jews were. None of the Christian characters played the ugly and vicious role Shylock did in Nazi propaganda. When one encounters this allegedly sophisticated Shakespeare-made-the-Christians-worse evasion, one has to ask why the Nazis put on fifty productions of Merchant. Because of its critique of the Christians?

Basically, this becomes Rosenbaum’s first and last line of defense: If you claim that there’s a sympathetic reading of Shylock to be had, then you’re a Nazi. (Or, at best, a Nazi-sympathizer.)

One could delve into the problems with Rosenbaum’s defense. (For example, just because Shylock can be played as a racist caricature, it doesn’t follow that he should be. Or perhaps the fact that the German productions would have been translated, offering plentiful opportunities to strip out Shakespeare’s theme and replace it with something uglier.) But it’s pointless, because there is no actual substance behind Rosenbaum’s repeated insistence that “if the Nazis performed it, it must be evil”. If he pulled this online, he would be rightfully called out for Godwinizing the discussion.

(And it was, in fact, this particular bit of intellectual dishonesty that prompted me to start writing this response.)

HEDGING MY BETS

With that being said, I have never performed a deep study of The Merchant of Venice. And even my casual readings and viewings have made it abundantly clear that there are no easy answers when it comes to the text. For example, before offering any other rationale, Shylock says, “I hate him for he is a Christian.” And there remains the open question of exactly how the behavior of the Christians in the play would have been interpreted by an Elizabethan audience: We see their behavior as abhorrent and are thus inclined to interpret them as negative portrayals. But if you don’t view their behavior as abhorrent, does that remain true? Is the play condemning them or are we condemning them?

But whatever complexities the text may offer, it remains absolutely true that it explicitly says both that, “Shylock does what he does because Antonio did what he did.” and “There is no difference between a Jew and a Christian.”

Any responsible reading of the text must take those elements of the text into account. It cannot, as Rosenbaum does, simply ignore them.

The Shakespeare Wars: Shakespeare Myopia

I’ve been reading The Shakespeare Wars by Ron Rosenbaum and writing short essays in response to some of the more dunder-headed bits of scholastic self-indulgence that Rosenbaum has been discussing. (Rosenbaum also discusses a lot of good stuff, and despite some reservations over the quality of Rosenbaum’s writing, I recommend checking his book out for a good review of current controversies in Shakespearean scholarship.)

I’ve been reading The Shakespeare Wars by Ron Rosenbaum and writing short essays in response to some of the more dunder-headed bits of scholastic self-indulgence that Rosenbaum has been discussing. (Rosenbaum also discusses a lot of good stuff, and despite some reservations over the quality of Rosenbaum’s writing, I recommend checking his book out for a good review of current controversies in Shakespearean scholarship.)

Today I want to take a peek at one facet of the debate between the theories of the Lost Archetypes and the Revisions.

To offer a simplistic summary: All modern editions of Shakespeare are based on versions of the plays published during the late-16th and early-17th centuries. All of these texts feature various typo-like errors that must be corrected.

In the case of nineteen plays, however, things get a little more complicated because we have multiple versions of each play published during or near Shakespeare’s life. (For example, we have three extant versions of Hamlet.) In producing a modern edition, the differences between these versions must be resolved in order to produce a single text.

This is where the difference between the Lost Archetype theory and the Revision theory comes into play.

The Lost Archetype theory says that Shakespeare wrote one, authoritative version of each play. In other words, the original manuscript, written in Shakespeare’s own hand, is the Lost Archetype for each play. The differences between the primary sources for a play are the result of different editions making different errors in transcribing Shakespeare’s text, and our goal in rendering a modern edition is to remove these errors.

The Revision theory, on the other hand, says that Shakespeare continued revising his plays throughout his lifetime and that the differences between the various versions of each play are the result of Shakespeare’s rewrites.

For example, the 1604 Second Quarto of Hamlet contains an entire soliloquy which is missing from the 1623 First Folio. Under the Lost Archetype theory, this soliloquy was somehow lost: Perhaps the page was misplaced. Or the typesetter accidentally skipped it. Or the typesetter was working from a theater promptbook that had been cut for length. Basically, there are many different theories to explain how this soliloquy went missing, but the underlying theory is that Shakespeare intended the soliloquy to be part of the play and, therefore, it should be included in the modern text.

Under the Revision theory, on the other hand, the idea is that Shakespeare rewrote the play. At some point between 1604 and 1623, Shakespeare came back to Hamlet and decided to cut that soliloquy. Maybe he cut it for length or pace; or because it was repetitive; or because it cast an inaccurate light on Hamlet’s character. Again, there are many theories for why Shakespeare might have cut it, but the underlying theory is that Shakespeare changed the play and we should ask the question, “Why did he change it?”

TAYLOR’S FOLLY

With these two theories in mind, let’s take a closer look at a particular argument proffered by Gary Taylor (one of the primary advocates for the Revision theory), as shown by Rosenbaum in The Shakespeare Wars:

“There’s always someone standing between you and him. It’s like being at a cocktail party and there may be one person in the room that really interests you most, but there’s other people around, and so it’s like seeing Shakespeare across the room at a party. There’s always going to be parts of him you can’t see, and which parts you do see is partly accidently…”

And yet, he tells me, it was his communion with the inky traces of the compositors and typographers that led him to see, through an ink-smudged glass, darkly, a vision of Shakespeare as a reviser.

It was a reaction to what he calls the “demonization” of the compositors by the partisans of the Lost Archetype who try to blame the variations between the two Hamlets on the inattention, the “eye skip”, the carelessness, the willfulness and wandering eyes of an array of compositors. On the contrary, Taylor believes, “You need only one agent to account for all those variations and that’s the agent who’s present in all these cases: Shakespeare.”

And right there is the point where Taylor’s logic runs aground.

I can say this with a fair degree of confidence for three reasons:

(1) We know that compositors made errors because the publisher would frequently correct them during a print run. In other words, there are differences between the various copies of the 1604 Second Quarto of Hamlet that survive today. I suppose one might still imagine that Shakespeare was actually at the printers, looking over their shoulders and doing rewrites while the book was being published, but…

(2) Compositor errors are not limited to the work of Shakespeare. They can be found in every single book published in this era. The King James Bible is particularly noted by many scholars because it contains so few errors compared to other texts of the era, but it still contains hundreds of known errors. And maybe, like our hypothetical Shakespeare, every author of the era — including the translators of the King James Bible — made a habit of going down to the print shop to make rewrites on the fly, but…

(3) The errors continue long after Shakespeare is dead. For example, the First Folio was published in 1623 (seven years after Shakespeare was dead). Over the course of the 17th century it was followed by the Second Folio (1632), Third Folio (1663-1664), and the Fourth Folio (1685). These later editions are essentially never used in the creation of modern editions because

(a) We know that they were based on the text of the First Folio. (In other words, the typesetters of these later editions were looking at copies of the First Folio or other editions derived from the First Folio.)

(b) They introduce even more errors of the exact same type seen in the earlier texts. (They also attempt to fix some of the existing errors, but since they’re doing so without any reference to a primary text, we have no particular reason to invest trust or value in their decisions.)

This is what I refer to as Shakespeare Myopia. Shakespeare is such a towering figure in English literature that lots of people will study him exclusively. And this, in my experience, results in all kinds of half-assed theories that wouldn’t have any kind of traction if people would look outside of the Shakespeare Box once in awhile.

(Another example of Shakspeare Myopia can be found all over the so-called “Authorship Question”. For example, people looking to discredit Shakespeare’s authorship of his own plays will often declaim the lack of historical evidence we have for Shakespeare’s life. The only problem? We have more documented evidence of Shakespeare’s life than for any other Elizabethan playwright with the possible exception of the always self-promoting Ben Jonson. For those interested in a thorough debunking of the “Authorship Question”, I recommend Irvin Leigh Matus’ exceptional Shakespeare, In Fact.)

SHADES OF GREY

In any case, unless one is willing to believe that Shakespeare was still rewriting his plays as late as 1685, we know for an absolute certainty that at least some of the variances between the texts are the result of typesetting errors and not Shakespeare’s revisions.

And if we have concluded that some of them must be, then doesn’t it make sense to apply Ockham’s Razor and say that all of them are the result of typesetting errors?

Well… maybe.

But misplacing a whole soliloquy seems like quite the slip of the eye, doesn’t it? Maybe we could hypothesize that the soliloquy was on a page all by itself in the manuscript and either that page got misplaced or two pages got flipped over at the same time or… Well, any number of things. But it seems just as likely that the soliloquy was deliberately removed from whatever text the compositor of the 1623 First Folio was working from.

But here we run into two more problems with the Revision theory:

(1) We have no way of knowing who did the revising. It might have been Shakespeare who cut that soliloquy. But it could just as easily have been a theater manager who thought the play was too long. In other instances, of course, words have been added. But it was a well-documented practice for other playwrights to touch-up older works and it remains a common (if often frowned upon) practice in the theater for promptbooks to reflect improvisations from the actors of the current production.

(2) We have no way of knowing which text is the original and which text is the revision. It’s easy, for example, to assume that the 1623 First Folio text of Hamlet would be the revision of the 1604 Second Quarto text. But the 1623 text could just as easily be the copy that Shakespeare originally gave to the Globe Theater to perform in 1600, while the 1604 text is the result of Shakespeare revising the text before submitting it for publication.

Personally, I feel like attempts to apply a one-size-fits-all solution to the relationships between the various primary sources of Shakespeare’s plays is somewhat foolish. Among these theories:

(a) Bad Quartos. The result of pre-copyright publishers trying to surrepititously obtain a copy of a play to publish without paying for it, either by having someone in the theater trying to write down the lines as fast as they can or by hiring a former actor to reconstruct the text from memory.

(b) Revision. Shakespeare rewrote the plays to lesser or greater extents.

(c) Derived texts. Some texts in the First Folio appear to have been set from previously published quartos; some from manuscript (although whether it would be Shakespeare’s original or a scribed copy is often open for debate); some from theater promptbooks.

In my opinion, all of these have some merit. In fact, it makes sense that different texts would have different relationships (both to each other and to Shakespeare). It seems silly to argue that if King Lear was rewritten by Shakespeare, then it must also be true that Shakespeare rewrote Hamlet. (Or, vice versa, that if Shakespeare didn’t rewrite Hamlet, it must be true that he didn’t rewrite King Lear.)

But this is so often what happens: Somebody comes up with a nifty theory and then they try to apply it everywhere. They overreach.

For example, A Midsummer Night’s Dream exists in three primary sources: The 1600 First Quarto, 1619 Second Quarto, and 1623 First Folio. We are almost completely certain that the 1619 Second Quarto was set from a copy of the 1600 First Quarto (based on textual similarities in which the 1619 text duplicates the unusual spellings, incorrect speech attributions, typographic features, and various other errors of the 1600 text in a way that only makes sense if the compositor of the 1619 text were looking at the 1600 text).

In most cases, therefore, moden editor would largely ignore the 1619 text as a mere reprint. But here it gets weird because the 1623 First Folio was almost certainly set from a version of Q2 (once again we have similarities between the texts, but where the 1619 Second Quarto differs from the 1600 First Quarto, the 1623 First Folio always follows the 1619 Second Quarto). And, once again, we would normally ignore this text… except that information from the theater’s prompt-book has apparently been added to it.

(How do we know it was a prompt-book? Several bits suggest it, but the clincher is a stage direction in V.1: “Tawyer with a trumpet before them.” Tawyer was the name of a company member, not a character.)

Dover Wilson postulated that a copy of the 1619 Second Quarto must have been used as a prompt-book at the Globe and then that prompt-book was used to set the type for the 1623 First Folio. Some doubt has been cast on this theory due to errors in various entrances and exits (which would never be tolerated in a theater manager’s copy of the script), but it seems more likely that those errors were introduced by the compositor.

The result is that we have a very clear textual lineage for these scripts: The 1600 First Quarto was published from some unknown source. The 1619 Second Quarto was set from the 1600 edition and was accurate enough that the theater started using it as their promptbook, which was then used (in turn) for the 1623 First Folio.

But I think it would be foolish to draw any broad conclusions from this. (For example, by assuming that all First Folio texts were printed from theater promptbooks.) When it comes to the history of Shakespeare’s texts, there are no easy answers. No one-size-fits-all solutions that will remove all doubts. (In this, they are much like the plays themselves.)

Current Projects

I know things have been pretty quiet around here of late. I’m afraid that’s because everything else in my life has been so ridiculously busy. So, on that note, here’s a quicky summary of upcoming projects I’m involved with:

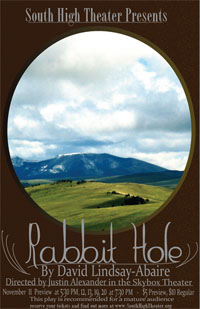

I directed David Lindsay-Abaire’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Rabbit Hole for South High School. Most high school theater can only be loved by the parents, but South High Theater sets a higher standard for itself and Rabbit Hole achieves it. (I may be biased, but if it didn’t, then I wouldn’t be promoting it here.)

Rabbit Hole has two performances left: November 19th and 20th (Thursday and Friday), both at 7:30 PM. Reserve your tickets and check it out.

I’ve also founded the American Shakespeare Repertory, and we’re getting ready to kick-off our inaugural project: The Complete Readings of William Shakespeare will present every play, poem, and sonnet (along with a sampling of the apocrphya) from 2009-2011. It represents the unique opportunity to experience in performance all of Shakespeare’s masterpieces, including those rarely or never seen, in a way that hasn’t been possible since the King’s Men originally performed them 400 years ago.

On November 23rd, the series premieres with MACBETH at the Gremlin Theater. Join us for a night of blood, murder, and mayhem as Shakespeare’s darkest tragedy is brought to vivid life.

STARRING

Macbeth – Justin Alexander

Lady Macbeth – Elizabeth Grullon

Macduff – Neal Beckman

Lady Macduff – Amanda Whisner

Malcolm – Jordon Johnson

Witch 1 – Gail Frazer

Witch 2 – Susannah Handley

Witch 3 – Hannah Steblay

Angus/Siward – Ann Gerstner

Donalbain – Kelly Bancroft

Fleance/Young Siward – Emma Mayer

Lennox – Sarah Martin

Ross – Gabe Heller

Seyton – Martha Heyl

Stage Manager: Sarah Holmberg

SPONSORED BY

Gremlin Theater’s Corleone: A Shakespearean Godfather

And coming soon…

Two Gentlemen of Verona – December 2nd – Pillsbury House Theater

Coriolanus – December 9th – Open Eye Figure Theater

Twelfth Night – December 16th – South High Skybox Theater

AND BEYOND…

In January I’ll be appearing in Starting Gate’s production of Moss Hart’s Light Up the Sky!

In May I’ll be assistant directing Walking Shadow Theater’s production of Trasndimensional Couriers Union.

… AND HERE AT THE ALEXANDRIAN

I’ll be doing my best to get back to regular updates and fresh content. Promise.

The Shakespeare Wars: Thus Diest Common Sense

I’ve recently been reading The Shakespeare Wars by Ron Rosenbaum. The book is far from perfect (Rosenbaum has a tendency to circle around a topic in endless repetitions and effusing instead of explaining), but it does offer a rather nice survey of several scholastic controversies currently swirling around Shakespeare’s works.

I’ve recently been reading The Shakespeare Wars by Ron Rosenbaum. The book is far from perfect (Rosenbaum has a tendency to circle around a topic in endless repetitions and effusing instead of explaining), but it does offer a rather nice survey of several scholastic controversies currently swirling around Shakespeare’s works.

And thus, of course, it provides me with ample opportunities to brush up against the uniquely eruditic idiocies that only literary scholars seem capable of.

If you’re looking for the really interesting, fascinating material, then you should hunt down a copy of The Shakespeare Wars and dig in. For an explication on the stupid stuff, just buckle your seat belt and hang on for the ride.

I’m going to start by discussing a scholarly emendation of a line from Hamlet. The actual bit of dialogue being discussed is relatively minor in the grand scope of things, but I think it serves as a more-than-adequate example of the hubris and foolishness to be found in much of Shakespearean textual work. (In the bigger picture, this seems almost inevitable: Ask several thousand PhD candidates to masticate the well-worn corpse of Shakespeare’s work every single year and you’ll end up with all kinds of crazy shit being postulated by people desperate for a thesis statement.)

Before we begin, let me lay out some groundwork: All modern editions of Hamlet are based on three source texts — the Bad Quarto (Q1); the Good Quarto (Q2); and the First Folio (F1). The first two texts were published during Shakespeare’s lifetime (although not necessarily with Shakepeare’s direct involvement) and the last was the first complete collection of Shakespeare’s plays (published after his death in 1623). All of these editions differ from each other. (The Bad Quarto is significantly different and is theorized to be a text reconstructed from memory by an actor who performed in a touring production.) The exact reasons for these differences is under debate (something I’ll touch on in a later essay), but at least some of the differences are the result of the typesetters making mistakes. Thus, modern editors are faced with imperfect, conflicting texts and must figure out how to edit them in an effort ot produce a clean and accurate version of the play.

With that in mind, let’s take a look at an excerpt from Chapter Two of The Shakespeare Wars:

In 1997, when Harold Jenkins, former Regius Professor at the University of Edinburgh and editor of a leading scholarly edition of Shakespeare’s play, went to see Kenneth Brannagh’s film version of Hamlet, he was both excited and nervous. Sitting in his home two years later, the ninety-year-old scholar became animated as he described to me the anticipation he felt as the play reached the seventh scene, in the fourth act, when Laertes, huddling with Claudius, reacts to the news that Hamlet is back in Denmark.

It’s a moment in which Jenkins had made a crucial single-word change in his influential, encyclopedic Arden edition of Hamlet, and he wondered whether Branagh would adopt his emendation. “I listened to see what was coming,” Jenkins told me. “What would [Laertes] say?”

On screen the actor playing Laertes turned to the King and told him, apropos Hamlet (who had killed [Laertes’] father): “It warms the very sickness in my heart / That I shall live and tell him to his teeth / ‘Thus diest thou…'”

“Thus diest thou! Yes!” the dapper, mild-mannered Jenkins exclaimed with all the fervor of a soccer fan celebrating a goal. “He got it right. And of course it is so much more effective.”

Effective or not, Jenkins believes he is not “improving” Shakespeare but restoring to us Shakespeare’s own long-lost word choice. In the two most substantial early texts of Hamlet that have come down to us from his time — the 1604 Quarto and the 1623 Folio versions — Laertes doesn’t say, “Thus diest thou.” He says “Thus didst thou” in one and “Thus didest thou” in the other.

But Jenkins believes that what he has done is recover the word Shakespeare wrote with his own hand and quill — before it was corrupted through carelessness in the printing house or the playhouse.

Jenkins is wrong.

I say this for two reasons:

(1) You have only two sources of information. They are both telling you the exact same thing. The only possible reason to suspect that they’re both lying to you is if the resulting sentence were nonsensical. But it isn’t nonsense. It makes perfect sense. Ergo, there is no rational reason for making any sort of change.

(2) Within the context of the play, “Thus didst thou” is poignant and specific: Laertes is planning to kill Hamlet the same way that Hamlet killed his father, and in that moment of revenge he wants Hamlet to understand exactly why he’s being killed. “Thus diest thou”, on the other hand, is generic. So you’re not only changing the line for no particular reason, you are simplifying it and robbing it of its specific and dramatic content.

Now, here’s the important thing: You see #2 up there? I think it’s an interesting point. But it’s also completely irrelevant. Whether I think “didst” is more interesting than “diest” is meaningless when it comes to making reasonable corrections to the text of Hamlet. It’s just as irrelevant as Jenkins’ opinion that “diest” is “much more effective” than “didst”.

And let’s be clear: It’s certainly possible that Shakespeare wrote “Thus diest thou”. But by the same token it’s just as likely that he wrote “Why didst thou”. Once you go looking for words that could be different (without any indication that they should be different), you’ve turned all Shakespeare into a scholastic mad lib.

OF MOONS AND MURALS

I think there’s also something perverse about looking for problems where none exist when there are plenty of places in Shakespeare’s works where we have actual problems… some of them without any clear solution.

In Act 5, Scene 1 of A Midsummer Night’s Dream there is a play-within-a-play. During that play, the character of Wall exits the stage and one of the audience members says, “Now is the mural down between the two neighbors.”

Or, at least, that’s what it says in many modern editions of the play.

But we have only two primary sources for A Midsummer Night’s Dream: The First Folio (1623) and a quarto edition (1600).

The 1600 Quarto reads: “Now is the Moon used between the two neighbors.”

The 1623 First Folio reads: “Now is the morall downe between the two neighbors.”

These lines don’t make any sense. Clearly something is wrong. In 1725, Alexander Pope — the first English poet to make a living from sales of his published work — produced an authoritative edition of Shakespeare’s plays. In that edition, he created the emendation “mural down”.

But using the word “mural” to mean “wall” was something that Pope made up out of wholecloth. (In many dictionaries you will, in fact, find the origin of this definition cited to A Midsummer Night’s Dream.) But what are the odds that Shakespeare made up a word, the typesetters screwed it up, and then Alexander Pope reinvented it?

Many modern editions (including, for example, the Oxford edition) instead render this line as: “Now is the wall down between the two neighbors.” In doing so, they are imitating a line Bottom has later in the scene, when he says, “No, I assure you, the wall is down that parted their fathers.” Is that right? I dunno. It certainly sounds more plausible to me than “mural”. On the other hand, it has a significant influence on Bottom’s line — so if it isn’t right, the impact is felt beyond this single line.

SULLIED vs. SOLID

Here’s another fun one. Pretty much everyone is familiar with Hamlet’s famous soliloquy which begins, “O that this too, too solid flesh would melt…”

At the moment, however, there’s a significant debate about this line because Q2 reads: “O that this too too sallied flesh would melt…”

But here’s the weird part: The argument isn’t that “sallied” is the correct word (although the image it conjures forth of sallying forth to defend a besieged location is interesting, particularly since Hamlet immediately goes on to equate the situation to God turning a “cannon ‘gainst self-slaughter”… although you’ll also find the word “cannon” changed to “canon” in many modern editions). Instead, the argument is that the word should be “sullied”.

(You may find a few references online claiming that “sullied” comes from Q1. As far as I can tell, this is not true. Q1 also uses the word “sallied”, and you can see it online.)

What’s the truth here? Well, given a choice between either:

(a) Picking one version of the text and then using it exactly as it appears; or

(b) Picking one version of the text and then emending it to something else

I think (a) is the better bet if you’re looking to play the odds. On the other hand, given a choice between:

(a) Picking a word which appears in one good edition; or

(b) Emending a word found in one good edition and also used in a bad edition

I think the question becomes a bit hazier.

I’m sticking with “solid” for now… but I could be wrong.

Archives

Recent Posts

- Review: Mothership Adventure Sphere – Part 5: Airlock Series

- Ptolus: Running the Campaign – Undead for Effect

- In the Shadow of the Spire – Session 48C: Entering the Tomb

- Review: Mothership Adventure Sphere – Part 4

- Ex-RPGNet Review: The Mortality of Green

Recent Comments

- on Review: Mothership Adventure Sphere – Part 5: Airlock Series

- on Review: Mothership Adventure Sphere – Part 4

- on Reviews: Mothership Adventure Sphere

- on Remixing Avernus – Part 3F-A: Dungeon of the Dead Three (Design Notes)

- on Review: Mothership Adventure Sphere – Part 4

- on Thought of the Day: Why D&D?

- on Review: Mothership Adventure Sphere – Part 4

- on Review: Mothership Adventure Sphere – Part 4

- on Whither the Dungeon: Goblin Trouble

- on Storm King’s Remix – Part 3B: The Giant Lairs