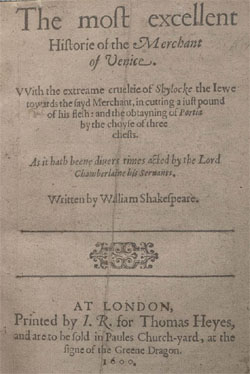

One of the two main plots in The Merchant of Venice, of course, revolves around the pound of flesh which Anthonio forfeits to Shylock when he fails to repay his bond. Although an Italian collection of stories entitled Il Pecorone is usually cited as the primary source of this plot (insofar as it most closely resembles the story in Shakespeare’s play), the truth is that there were dozens of variations of this story to be found and it’s likely that Shakespeare was familiar (or at least acquainted) with several of them. (There are even versions in which it is the Christian who is attempting to claim a pound of flesh from the Jew.)

One of the two main plots in The Merchant of Venice, of course, revolves around the pound of flesh which Anthonio forfeits to Shylock when he fails to repay his bond. Although an Italian collection of stories entitled Il Pecorone is usually cited as the primary source of this plot (insofar as it most closely resembles the story in Shakespeare’s play), the truth is that there were dozens of variations of this story to be found and it’s likely that Shakespeare was familiar (or at least acquainted) with several of them. (There are even versions in which it is the Christian who is attempting to claim a pound of flesh from the Jew.)

One of these stories is Alexander Silvayn’s The Orator, which shares certain turns of phrase with The Merchant of Venice and contains one particular passage which highlights a potentially revealing continuity glitch in the play:

Neither am I to take that which he oweth me, but he is to deliver it me. And especially because no man knoweth better than he where the same may be spared to the least hurt of his person, for I might take it in such a place as he might thereby happen to lose his life. What a matter were it then if I should cut off his privy member, supposing that the same would altogether weigh a just pound?

Combined with the fact that Elizabethan playwrights often used “flesh” as a pun for “penis” (Shakespeare does it multiple times in Romeo & Juliet, for example), it certainly raises the question of exactly what Shylock means when he says “an equal pound of your fair flesh to be cut off and taken in what part of your body pleaseth me” (Act 1, Scene 3). The sexual pun that also evokes the castration imagery of circumcision certainly isn’t a slam dunk from a textual standpoint, but it is a legitimate option.

Of course, by the trial scene the nature of the bond has transformed. Instead of being taken from “what part of your body pleaseth me”, Portia describes the bond as allowing “a pound of flesh to be by him cut off nearest the merchant’s heart”.

This sort of continuity glitch is far from unusual in Shakespeare’s plays. (In fact, strict continuity is a modern bugaboo that Shakespeare often ignored in favor of the immediate needs of dramatic effectiveness.) But this particular glitch may be deliberate.

One of the key distinctions drawn between Jews and Christians by Elizabethan theologians focused, perhaps unsurprisingly, on the matter of circumcision. While the Jews believed in a physical circumcision marking their covenant with God, the Christians made a metaphorical circumcision of their hearts (as described by Paul). Thus, by shifting the pound of flesh from Anthonio’s “privy member” to his Christian heart, Shakespeare is shifting from one sort of circumcision to the other. More than that, Shylock’s surgery takes a metaphorical Christian ritual and turns it into a literal Jewish ritual, while simultaneously allowing him to take from Anthonio the very thing which makes him Christian. (Consider, too, that Anthonio in this same scene is given a long speech explicitly calling out the hardness of Shylock’s “Jewish heart”, emphasizing this Elizabethan distinction between Jew and Christian.)

The ritualized nature of Shylock’s intended murder of Anthonio is now obvious. What’s particularly compelling about it, however, is that it is ritualized through the legal system; i.e., through the system of laws which defines the nation. In combination with the religious elements inherent in the circumcision imagery, Shakespeare successfully unifies all of the societal disruptions personified by “the Jew” in Elizabethan consciousness into the Jewish boogeyman of ritualized murder.

The poetic justice of Shylock’s punishment also becomes clear as the full importance of the “pound of flesh” is revealed. Shylock’s forced conversion is often viewed by modern readers and commentators as a needless cruelty, and its harshness is not tempered when one learns that it is a creation unique to Shakespeare’s version of the story. But Shylock was not threatening merely Anthonio’s life; he was threatening to take from him his Christianity. In the giving of justice, therefore, it lies with Anthonio to now “better the instruction” (in Shylock’s words) and “hoist him by his own petard” (in Hamlet’s). As Shylock tried to unmake Anthonio as a Christian, so his punishment is to be unmade as a Jew.

Originally posted on December 4th, 2010.