IN THE SHADOW OF THE SPIRE

Session 11A: Into the Caverns of the Ooze Lord

At the same moment, two of the greenish, ooze-like creatures dropped from the ceiling of the chamber and landed in front of the passage. They were not as large as the creature they had just defeated, but between the two of them the entire width and much of the height of the tunnel was filled.

In some design circles, there is a tremendous amount of focus and energy expended on making encounters mechanically interesting and/or mechanically novel. While I generally agree that a game  (and thus encounters) should be both mechanically interesting and varied, I also think that there’s currently way too much emphasis being placed on this.

(and thus encounters) should be both mechanically interesting and varied, I also think that there’s currently way too much emphasis being placed on this.

In my experience, you don’t need special snowflake mechanics in order to have memorable encounters. Of course, this doesn’t mean that mechanical interest isn’t important. Those who go to the other extreme and act as if mechanical design, mechanical effects, and mechanical interaction aren’t significant in the design and experience of combat encounters (and other gameplay elements) are blinding themselves and needlessly crippling their toolkit as a GM.

NOVELTY STAT BLOCKS

There are several ways to generate mechanical interest. For the moment, let’s limit our discussion to mechanical novelty in stat blocks – i.e., studding the stat blocks of your adversaries with unique abilities.

This is a particular area where it seems to have become fashionable to expend way too much effort on creating these unique, special snowflake stat blocks in the name of creating “memorable” encounters. There are 4th Edition modules, for example, where seemingly every single encounter features an orc with a different suite of special abilities.

Not only do I think this is unnecessary, I think it can actually backfire: One of the things which creates mechanical interest is mastering a mechanical interface and then learning how to interact with it. Chess doesn’t become more interesting if you only play it once and then throw it away to play a different game; it becomes less interesting because you never learn its tactical and strategic depths. Similarly, when every single orc is a special snowflake with a package of 2-3 unique abilities that aren’t shared by any other orc, you never get the satisfaction of learning about what an orc can do and then applying that knowledge.

A constant, never-ending stream of novelty doesn’t make for a richer experience. It flattens the experience.

This is why video games generally feature a suite of adversaries who each possess a unique set of traits, and over the course of the game you learn how to defeat those adversaries and become better and better at doing so. That mastery is a source of interest and a source of pleasure.

(Of course, conversely, most video games will also feature bosses or other encounters that feature special mechanics or unique abilities. I’m not saying you should never have something a little special; I’m just saying that when everything is “special”, nothing is.)

My general approach to stat blocks is basically the exact opposite of this novelty-driven excess: Not only do I get a lot of mileage out of standard goblin stat blocks, I’ll also frequently grab a goblin stat block and use it to model stuff that isn’t even a goblin.

The other big benefit, of course, is that this is so much easier. So there’s also an aspect of smart prep here: Is all the effort you’re expending to make every single stat block unique really paying off commensurately in actual play? For a multitude of reasons, I don’t think so.

SYMBIOTIC TACTICS

The other two goblins passed into the slime creatures and… stopped there. Their swords lashed out from within the protective coating of the slime, further harrying Agnarr.

Perhaps the primary reason I don’t think so, is that there are so many ways of creating novelty (including mechanical novelty) in encounters without slaving over your stat blocks. One way of achieving this is through the use of symbiotic tactics.

Basically, symbiotic tactics are what happens when you build an encounter with two different creatures and, in their combination, get something unique that neither has in isolation. The current sessions includes an extreme example of that in the form of the ooze-possessed goblins who can fight from inside the green slimes (and are, thus, shielded from harm).

Symbiotic tactics, however, don’t need to always be so extreme in order to be effective in shaking things up. A particularly common form of symbiotic tactics, for example, are mounted opponents: Wolf-riding goblins are a distinctly different encounter than either goblins by themselves or wolves by themselves.

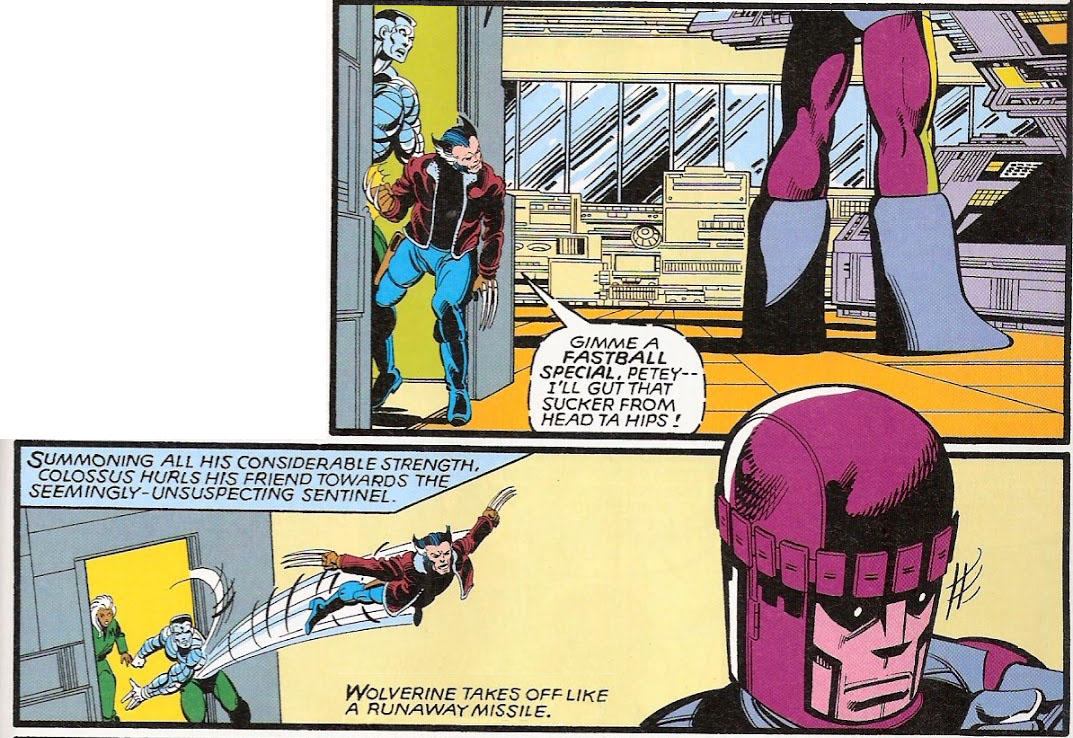

Symbiotic tactics also often appear in other media. For example—

—the fastball special from X-Men comics.

Unfortunately, to truly enjoy symbiotic tactics it’s not enough to simply design an encounter with multiple creature types. If you design an encounter with ogres and dragons and then the ogres simply fight separately from each other, it’s not necessarily a bad encounter, but it’s not employing symbiotic tactics. In order to have symbiotic tactics the goblins have to walk into the slime creatures.

(So to speak.)

Like many GMing skills, this is something that you can practice. Grab your favorite bestiaries, flip them open to two random pages, and then think about how those two creatures could cooperate to do something neither could do on their own.

Some actual examples I just generated:

- Dyrads + Ogres. A dryad is typically limited by their tree dependency, but this dryad is worshipped by a cult of ogres who carry their tree in a holy receptacle. The dryad is thus more mobile than usual, and will entrap opponents on the edge of their at will entangle ability so that the ogres can stand safely 10 feet away and use their reach to pound on them.

- Ankheg + Homunculus. An ankheg’s homunculus will fly above the surface, acting as a spotter for ankheg’s moving undetectably below the surface of the earth. (Yes, this does beg the question of how an ankheg ends up with a homunculus. Probably an interesting story there.)

- Harpy + Bebilith. The harpy uses their captivating song to keep victims passive while the bebilith snares them in their web.

What you end up may or may not be an encounter which even makes any sense. The point here isn’t necessarily to generate usable ideas. You’re flexing a muscle, and developing your sense of how creatures with disparate abilities can work together in interesting and creative ways.

In the process, you may start finding familiar themes: For example, after the three above I generated a Red Slaad + Ettercap. That can be another “stun ‘em, then web ‘em” combination like the Harpy + Bebilith.

Those types of discoveries are useful because you’ll begin building up a toolkit of such common tactical combinations that you can improvise with during play. But for the purposes of the exercise, try to pushing past the repeats and finding something unique. For example, the ettercaps might use their webs to stick the red salads to the ceiling. When the PCs enter the cavern, the ettercaps slice their webs and the red salads drop down all around them in an unexpected ambush.

Similarly, remember that you’re not necessarily trying to get their mechanical abilities to interact with each other in a purely mechanical way. It’s OK if that gives you an interesting idea, but it’s also limiting. Think outside the mechanical box and look at how these creatures might actually interact with each other. If that takes you back towards the mechanics, great! If it doesn’t, also great!

The final note I’ll make here is that this is not something I typically spend a lot of time (or any time) prepping before play. When you’re first exploring symbiotic tactics, it may be something that you do want or need to include your prep notes. But as you gain experience (as you exercise the muscle), you’ll likely find that you can dynamically figure out how different creatures can interact with and mutually benefit each other on the battlefield during actual play. You’ll be able to just focus on designing general situations (“there are ooze-possessed goblins and slime creatures in this area”) and then discover the rest of it during play. (Which will also have the benefit of allowing your encounters to dynamically respond to the actions of your PCs without losing depth or interest.)