Should the GM hide their rolls behind a GM screen or should they roll openly where the players can see the results?

A lot of people actually think that hiding their dice rolls is the primary or even ONLY reason for a GM to use a screen, and this can even mire discussions about using GM screens in a debate about whether or not the GM should be hiding their rolls. And the debate about whether or not a GM should be hiding their rolls can often be entirely swallowed up in an argument about whether or not a GM should be fudging their rolls. (Which is, according to these debates, the only possible reason a GM would have for hiding their rolls.)

At this point, as you can see, the argument is already several layers deep in largely unexamined premises.

Let’s see if we can unpack things a bit.

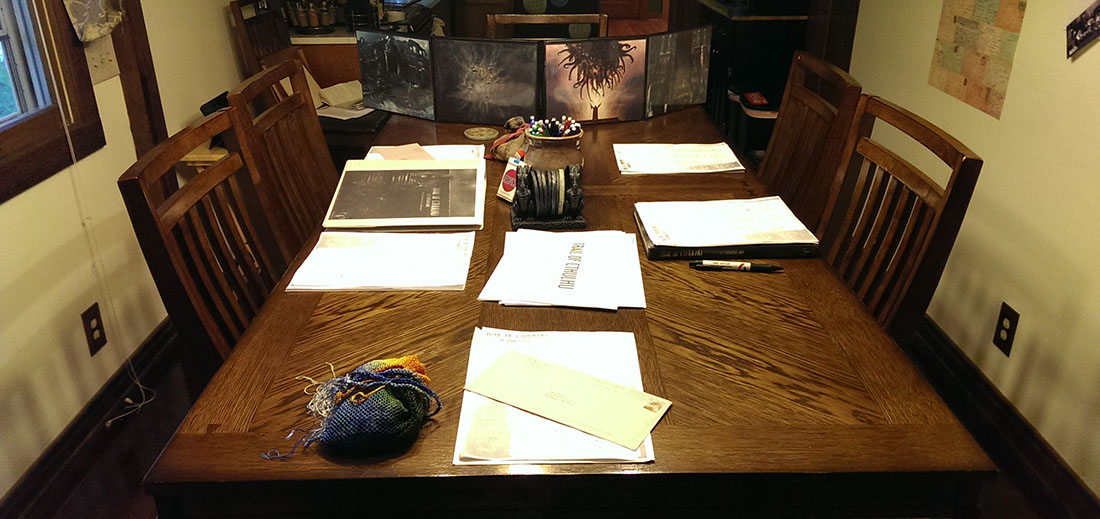

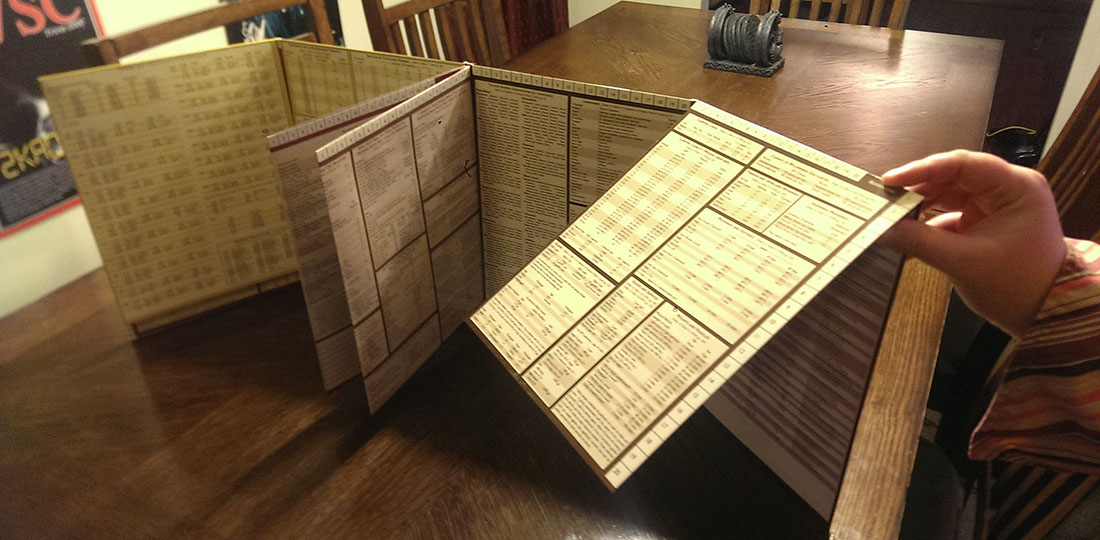

First, I discuss a bunch of great reasons for using a GM screen in On the Use of GM Screens, and hiding your dice rolls doesn’t even make the list. In fact, it’s fully possibly to use a GM screen and NOT hide your dice rolls. So let’s lay aside the idea that these are intrinsically linked.

Second, for the purposes of this post, let’s take it as a given that the GM should never fudge their rolls.

Having discarded fudging as a motivation, why would a GM want to hide their rolls? In my experience, there are three factors:

Convenience. As I mentioned, there are a lot of great reasons for using a GM screen. Therefore, although I don’t always us a screen, I do often use a screen. And while it’s possible to use a screen without hiding your dice rolls, it’s frequently inconvenient.

So when I’m using a screen, I mostly roll behind the screen because it’s easier. In most systems, it would be a huge pain in the ass to stand up and roll the dice on the far side of the screen every time I needed t roll.

Secrecy. There’s a wide variety of situations in which a dice roll is generating information which the players’ characters don’t have access to. (Or, at least, not immediately.) Therefore, it often makes sense also hide that information form the players.

Examples of this includes Stealth checks, random encounter checks, saving throws against illusions, and any number of other possibilities.

Dramatic Effect. When properly framed so that everyone at the table knows what number needs to be rolled on the dice — without doing any additional math; just “I need a 17 or better” — there can be an immense amount of suspense placed on the die roll and a hugely effective and emotional moment that happens when the dice are rolled and the result is immediately seen!

When a dramatic moment like this is happening, you certainly don’t want to under cut it by rolling the dice in secret! And you may even want to make a special effort to make sure the dramatic moment can happen (e.g., precalculating the die result needed even in a system where you typically don’t do that)!

D&D generally doesn’t frame rolls like this, but critical hits are an exception — everyone knows immediately what a natural 20 means! — and can give a little taste of what it can be like. On the other hand, Monte Cook’s Cypher System, if you run it properly, is set up so that almost every die roll works like this unless there’s a reason for secrecy (which, of course, provides its own dramatic impetus).

IN CONCLUSION

On that note, we can see how these three factors can be weighed for each roll to determine how we want to handle it.

So, for example, if I’m not using a GM screen, then I generally don’t care and just roll the dice, unless there’s a specific reason why secrecy is significant for a particular roll.

On the other hand, when I am using a screen, then I’ll generally roll behind the screen for convenience, unless the stakes are high enough that dramatic effect makes it worth the bother of standing up and rolling on the far side of the screen.

Other GMs, groups, or even game systems can easily have different opinions on the relative importance of these factors.

For example, maybe you’re playing a game with very few rolls and, therefore, every roll is a big, dramatic moment:

On the other hand, a GM might feel strongly about not giving their players the metagame knowledge that “there’s a reason this roll should be hidden, and therefore I’m hiding it,” and therefore they’d prefer to hide as many of their rolls as possible. (And this might be something that the GM only cares about because this particular group is prone to metagaming that knowledge. Or they may have had one of the players ask them to mask the metagame information because that will help them enjoy the game more.)

The point is that there’s not really a One True Way™ here. But hopefully a clear understanding of these factors will help you think clearly about when and why you’re hiding your dice rolls, and find the right solution for you, your group, and your game!

BONUS PLAYER TIP: GET DRAMATIC!

If you’re a player, you can set up your own dramatic dice rolls!

Remember that the basic concept is that (a) the stakes of the dice roll are clear, (b) everyone at the table knows what number you need to roll on the dice (with no additional modifiers); and (c) the roll is made in the open so that everyone can immediately see the result!

The stakes of the check put pressure on the roll; and the result of the roll being immediately known provides an instantaneous release of that pressure, regardless of whether the result is jubilant or catastrophic!

It is not, of course, unusual for the stakes of a roll to be known before the roll is made. Assuming you have access to all the other numbers involved, all you need to do to create your own dramatic dice roll is precalculate the result, announce it to the table, and then roll!

In some systems, as we’ve discussed, this will basically be done for you automatically. But in others, including D&D, you’ll need to jump through a couple extra hoops. (You might also need to ask the GM to give you an additional piece of information, like the DC of the check in D&D.)

The other thing to note, of course, is that if you try to make every single roll ultra-dramatic, the net effect will often be to make nothing dramatic. Excitement and emphasis can all too easily turn into tedium.

But if you choose your moments well, you can enhance the game for everyone at the table!