Newer readers may not be familiar with my old Reactions to OD&D series. If you haven’t read them, you may want to check them out first. It’s been more than half a decade since I last visited the series, but a recent discussion prompted me to track down and dust off some old notes.

Dave Arneson’s First Fantasy Campaign was published by Judges Guild in 1977. It “attempted to show the development and growth of his campaign as it was originally conceived.” (For those unfamiliar with the early history of D&D, the campaign in question is Blackmoor: The original dungeon, city, and wilderness setting in which Arneson created modern roleplaying games, and which would eventually become Dungeons & Dragons.) In practice, sadly, it is a deeply flawed book. It’s a haphazard concordance of lightly edited campaign notes, and Arneson, unfortunately, is not  particularly effective in explaining what many of these notes mean or how they were supposed to be used in actual play. The confusing nature of the book is heightened because its contents span both the original Blackmoor material (starting in 1970), revisions made to his home campaign after D&D was published in 1974, and further revisions made to the material in order to run it at conventions from 1975-77… and Arneson is rarely clear about exactly which material is which.

particularly effective in explaining what many of these notes mean or how they were supposed to be used in actual play. The confusing nature of the book is heightened because its contents span both the original Blackmoor material (starting in 1970), revisions made to his home campaign after D&D was published in 1974, and further revisions made to the material in order to run it at conventions from 1975-77… and Arneson is rarely clear about exactly which material is which.

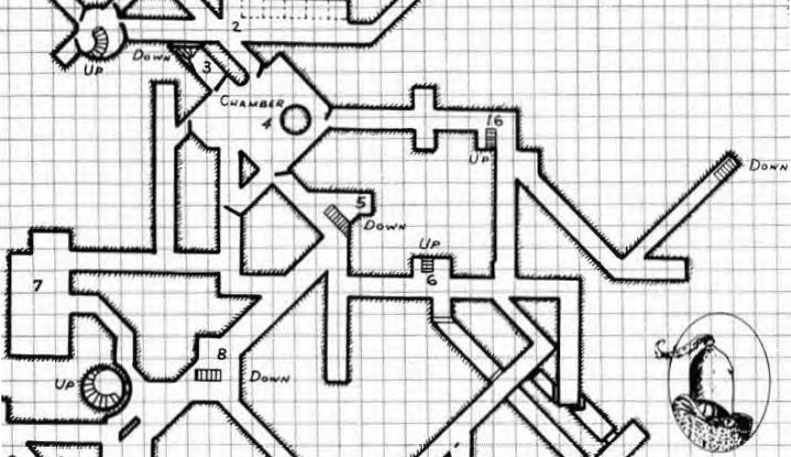

To take one small example, let’s consider the BLACKMOOR DUNGEONS section of the book. The material described here is literally Ground Zero for every single roleplaying game ever published (and, by extension, a huge percentage of pop culture, literature, and gaming over the past 50 years). Being able to get a glimpse into how Arneson actually ran those games would be an incredibly cool insight into a cultural watershed.

It’s frustrating, therefore, to discover that the First Fantasy Campaign makes it basically impossible to puzzle out what Arneson’s actual procedures were. I’ve spent an incredible amount of time pouring over this section of the book, and it remains a tantalizing enigma. I have, however, managed to work out a few details which I think others might find interesting.

Before we begin taking a close look at the text, however, it’s important to note a key point of context:

The Castle itself is still blank since it has been destroyed twice and rebuilt twice and then taken over by non-player Elves when the local adventurers were exiled. Thus, there are no sheets or goodies for it and only a sketch of its appearance. The Cavern sheet of Encounters is also lost (at least the first ones and the new one is in use). For these deletions I apologize.

The first six levels of encounters were prepared in the last two years for convention games, and set up along “Official” D&D lines. The last (7th – 9th and Tunnel Cavern System) are the originals used in our game. Additional crazy characters that got into the game over the years have been the Orcian Way and Sir Fang the Vampire.

(…)

Details on room, Cavern shapes for the Tunnel/Cave system have been lost or misplaced.

The first thing is that, as noted before, sections of Arneson’s notes as presented in the First Fantasy Campaign had been revised for convention play. This has, for better or worse, eradicated some amount of crucial information. The second is that the notes have also been partially (but not wholly) revised through actual play. And the third is that Arneson has deliberately not included some of his notes because he’s still using them in actual play. So you can already see that there are multiple layers of obfuscation here, made worse by the fact that some material has simply been lost due to the passage of time.

With that being said, let’s take a look at what Arneson is able to give us:

The other obstacle we almost immediately encounter here is poor proofreading.

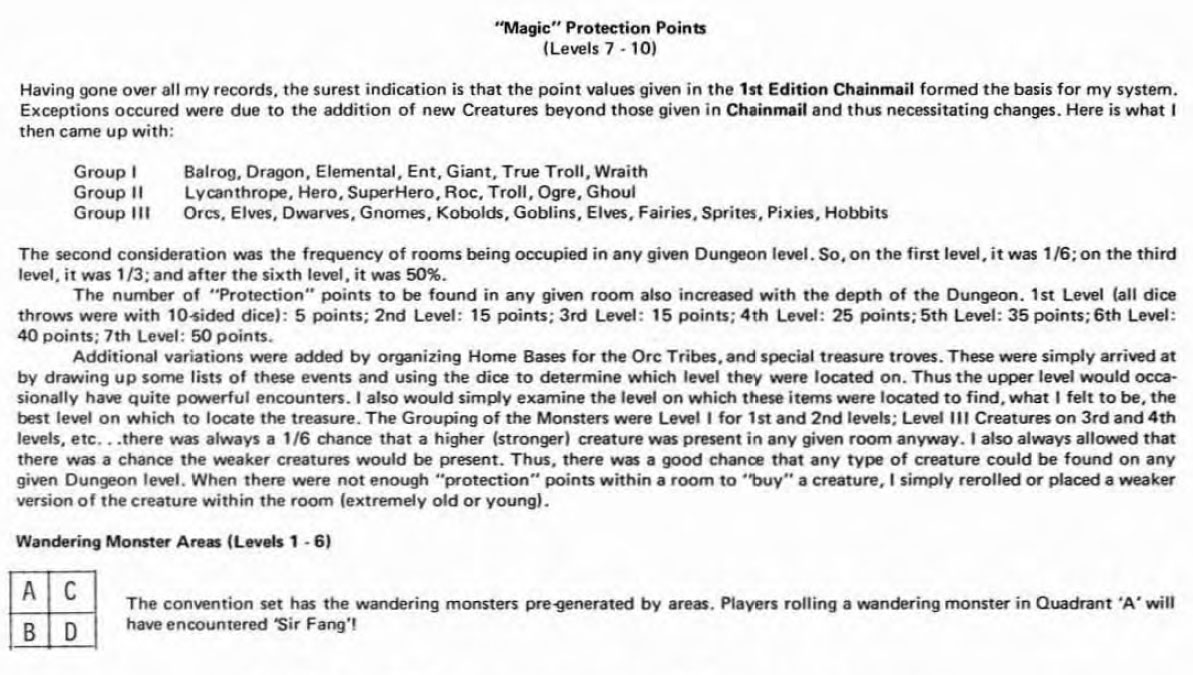

For example, Arneson lists Group I, Group II, and Group III for monsters. Later he says: “The Grouping of the Monsters were Level I for 1st and 2nd levels; Level III Creatures for 3rd and 4th levels, etc . . .” It seems fairly certain that “Level III” here should be read as “Level II”. One might initially conclude, both due to similarity of usage and the use of the capitalized term “Grouping”, that “Group I” and “Level I” are meant to be the same thing, but they are clearly not. (Balrogs on the 1st level of the dungeon would be an unusual design choice.)

Level I most likely refers to something equivalent to OD&D’s Monster Level Tables, so Arneson is saying to use the “Level I” (sic) tables for the 1st and 2nd level maps of Blackmoor. But if “Level I” and “Group I” aren’t the same thing, what are the Group listings used for? Ultimately, after going over the text several times, I’m forced to conclude that there simply isn’t any explanation given for why he created the Groups or what purpose they served. (Perhaps the order of the Groups was inverted and they ARE the same thing as the Levels, with Balrogs being Group III creatures instead of Group I?)

THE ARNESONIAN DUNGEON

Here’s what I think can be worked out with a fair degree of certainty. If you want to run Blackmoor in a style similar to how Arneson originally ran it:

1. You’ll need Level I, Level II, Level III, Level IV, and Level V monster tables.

- 1st / 2nd level: Level I

- 3rd / 4th level: Level II

- 5th / 6th level: Level III

- 7th / 8th level: Level IV

- 9th / 10th level: Level V

These tables are not provided in the First Fantasy Campaign, but it’s likely that these were D10-based tables. (He writes “all dice throws were with 10-sided dice.” Although this appears as almost a non sequitur in the text, the only logical use of the D10s here would be on the monster tables.) To stock the tables, I would probably try to pull a full list of monsters appearing on the Blackmoor key and the anomalous “Group” listings and then distribute them appropriately. (You might also consider stocking all of the creatures found in Chainmail.)

2. You’ll need to pull the point values for creatures from Chainmail. (And “due to the addition of new Creatures beyond those given in Chainmail” create point values where necessary. Additional values might also be gleaned from other sections of the First Fantasy Campaign.)

3. There is a “magic protection point” encounter budget that is determined by the dungeon level:

- 1st level: 5 points

- 2nd level: 15 points

- 3rd level: 15 points

- 4th level: 25 points

- 5th level: 35 points

- 6th level: 40 points

- 7th level: 50 points

(It feels extremely likely that the value listed for either the 2nd or 3rd level is a typo. I’m guessing the values should either be 10 & 15 or 15 & 20.)

4. For each room, roll an encounter chance:

- 1st level: 1 in 6

- 2nd level: 2 in 6

- 3rd+ level: 3 in 6

5. If an encounter is rolled, roll 1d6 for a 1 in 6 chance that the room includes “a higher (stronger) creature”.

(By default, I would assume “stronger” just means “use the next Level monster table,” but you might have some chance of using encounters from even stronger Level tables. There’s also “a chance that weaker creatures would be present”, but it’s not spelled out. It’s possible Arneson just winged that. You might also consider rolling 1d6 and using a weaker encounter on 1 and a stronger encounter on 6.)

6. Roll on the appropriate Level table, then purchase creatures of that type using the “magic protection point” budget. If you don’t have enough points, then either “reroll or place a weaker version of the creature within the room (extremely old or young).

(Arneson gives no indication for mixed encounter types. You might wish to do so: Perhaps generate No. Appearing using OD&D methods and then, if you have points left over, check for additional encounters in the same room. OTOH, Arneson’s keys and wandering encounters give no indication that he ever used encounters with mixed creature types.)

CONCLUDING THOUGHTS

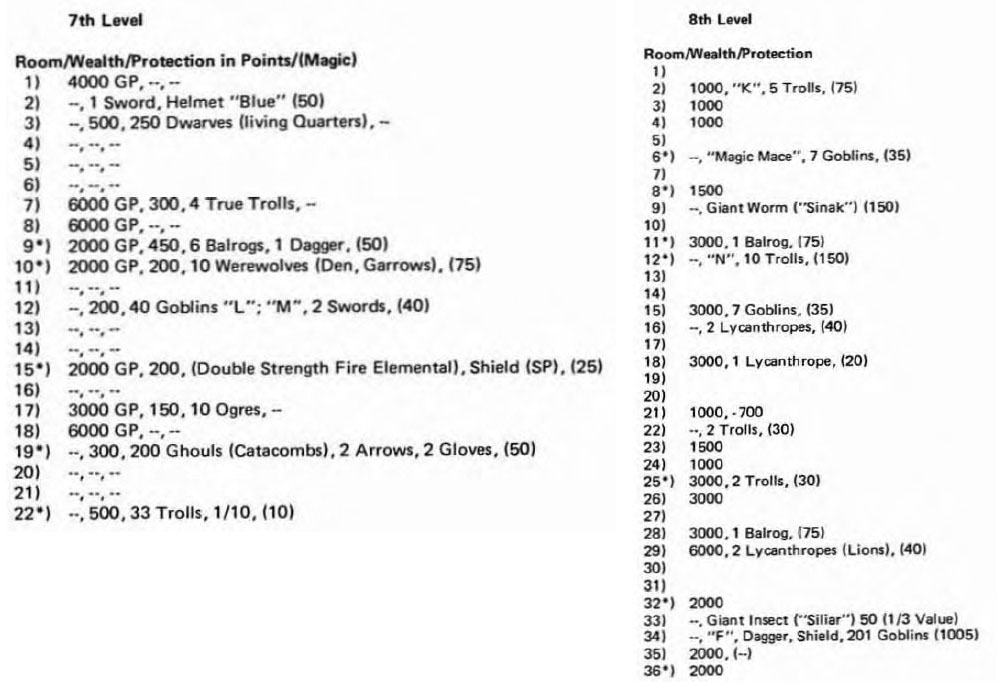

It remains unclear whether this was a “restocking” procedure that Arneson used between sessions or if he randomly determined results during play as rooms were being explored. It has the feel of a during-play system, but look at the key for the 7th to 10th levels (the ones set up according to the original schema and not revised for post-D&D convention play):

Note that the “Protection in Points” entry doesn’t consistently list points; it also lists specific creatures which have been generated with those points. If these are the notes Arneson was running the adventure from, then he was using the Protection Point system to restock. (For more on re-stocking dungeons, see (Re-)Running the Megadungeon.)

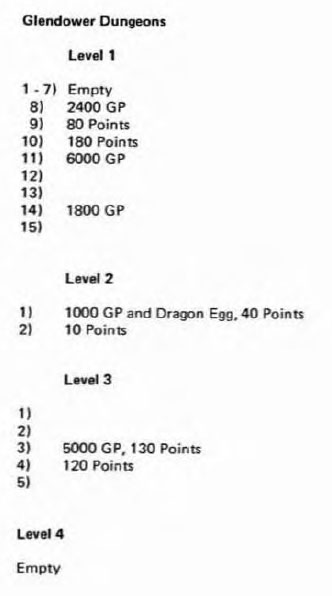

On the other hand, look at the similar key given for the Glendower Dungeons:

Those entries would appear to be the “Protection Point” or “Magic Point” values for those rooms, without the nature of that protection being predetermined. In the description of Loch Gloomen, Arneson also writes:

Those entries would appear to be the “Protection Point” or “Magic Point” values for those rooms, without the nature of that protection being predetermined. In the description of Loch Gloomen, Arneson also writes:

Defense of Area

30 – 180 Magic Points Creatures (two six-sided dice): 2) Giant; 3) True Trolls; 4) Roc; 5) Air Elemental; 6) Ogre; 7) Basilisk; 8) Goblins; 9) Ghouls; 10) Lycanthrope; 11) Balrog; 12) Dragon

The fairly clear intention here is to roll 3d6 x 10 to determine the number of Magic Points, and then roll 2d6 to determine the creature type.

So it seems quite likely that the Protection Point system was a flexible one. Arneson could:

- Stock the dungeon with specific creatures (using the Protection Point system as a procedural content generator).

- Quickly note “there should be X amount of protection in this room” (and then either specify it later or generate it during play).

- Randomly stock the dungeon room by room during play.

However, there are still several points which I find confusing. You might notice the “(Magic)” values given in the key for the 7th level of the Blackmoor dungeons, for example. It’s unclear what this entry is supposed to be: In any single entry it might be interpreted as an empty room’s encounter budget, the total cost of the listed “protectors”, or an unspent number of “magic protection points” that is meant to be spent in addition to the listed protectors. But no explanation seems to satisfactorily explain all instances (and any given explanation I’ve ventured is frequently contradicted by one of the usages). My suspicion is that he actually had a point system for determining how many magic items were located in each room (similar to the point budget for monsters in each room), but if so there’s no surviving evidence of how it would have worked.

Based on the key, it’s also likely that Arneson had some method for generating “Wealth” values independently from the Protection Points, but it’s not detailed here. (I’m guessing it was not dissimilar from that described in OD&D: 1 in 3 chance for treasure in occupied room; 1 in 6 chance in unoccupied room. And then rolls on some associated treasure table based on the dungeon level.)

It’s also unclear whether Arneson used wandering monster checks in addition to these room stocking procedures. It seems likely, but whatever method he may have used isn’t detailed. (Note that the poorly described “Wandering Monster Area” quadrant system described in the First Fantasy Campaign is part of the revision done to the material for convention play.)

Arneson also mentions that he would intermittently create “Home Bases for the Orc Tribes” and “special treasure troves”. These appear to have been completely arbitrary in their creation, but he would randomly roll to determine which level of the dungeon they would be added to. (“Thus the upper levels would occasionally have quite powerful encounters.”) The special distinction of the “Home Bases for the Orc Tribes” (as opposed to lairs for other creatures) seems significant, but I’ve been unable to tease it out. (And it may be entirely illusory.) There were four orc tribes in the campaign: Red Eye Orcs, Orcs of the White Hand, Isengarders, and Orcs of the Mountains, but the only information given relates to outdoor adventures, and it’s unclear what their agenda/function within the Blackmoor dungeon would have been.

I’ll also admit that I stopped trying to make sense of Arneson’s key for Blackmoor when I realized that he had 32 dwarves keyed to a room that’s 20′ x 10′. In the lower levels, there’s a point where he keys “250 Dwarves (living quarters)” into a room 10′ x 40′ long. There’s clearly some method to the madness here, but it’s beyond my ability to figure it out.