Go to Part 1

SPOILER WARNING!

SPOILER WARNING!

The following thoughts contain minor spoilers for Keep on the Shadowfell. If you don’t want to be spoiled, don’t read it. And if you’re in my gaming group then you definitely shouldn’t be reading it.

INTERLUDE: THE DEAD WALK

This is Interlude Three from Keep on the Shadowfell (pgs. 60-61). However, in order to extend the cult’s activities in Winterhaven, we’re going to change it slightly: Ninaran invokes the ritual, but doesn’t stick around. After performing the ritual, she simply crumples up the note from Kalarel and tosses it into one of the crypts. (The note does not name Ninaran, although it is signed by Kalarel.)

THE LESSER LICH: In order to rebalance the encounter, add a human mage (Monster Manual, pg. 163) and describe it as undead. (Experienced players should experience a nice frisson of terror when they see an undead in tattered robes throwing spells around.)

INTERLUDE: CULTISTS IN OUR MIDST

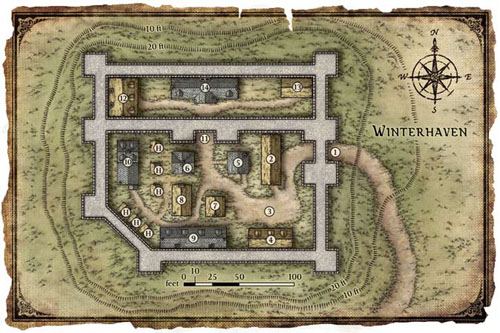

There are, in fact, more than a dozen cultists active in Winterhaven. At some point after “The Dead Walk”, Ninaran gathers these cultists together and leads an assault on Lord Padraig’s manor house.

If the PCs discover that Ninaran is a cultist before this encounter happens, they may be able to confront her before this encounter happens. If they kill her, she isn’t present but the remaining cultists will organize and attack the manor house in any case. (This will make the encounter easier for the PCs, and that’s just fine.) If they capture her and turn her over to Lord Padraig, he’ll lock her up in the Winterhaven Barracks. In that case, the cultists will first free Ninaran from the barracks and then attack the manor house.

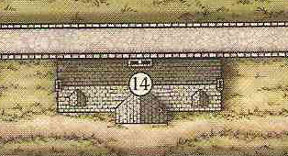

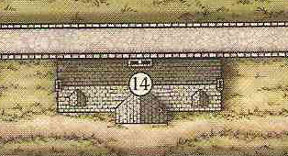

THE MANOR HOUSE – ENTRANCES

DOORS: The outer doors are barred from the inside (Break DC 20). The interior doors are not initially locked, although they can be if the cultists decide they need to barricade themselves (Break DC 16, Thievery DC 20).

DOORS: The outer doors are barred from the inside (Break DC 20). The interior doors are not initially locked, although they can be if the cultists decide they need to barricade themselves (Break DC 16, Thievery DC 20).

ARROW SLITS: The arrow slits on the south wall of area 1 are not large enough to serve as entrances. However, they do allow anyone inside to shoot through without impediment.

WINDOWS – FIRST FLOOR: The windows on the first floor are, in fact, 20 feet above the ground. They are not designed to be opened and are lined with lead, but are easily broken (Break DC 5).

WINDOWS – UPPER FLOORS: The windows on the upper floors are locked. ( Break DC 5, Thievery DC 15).

CHIMNEYS: There are three chimneys.

- EAST CHIMNEY (KITCHEN): This chimney is too small to climb down.

- WEST CHIMNEY (BEDROOM): This chimney is cramped and difficult to climb down (Athletics DC 20). Stealth checks suffer a -2 circumstance penalty while climbing in this chimney.

- NORTH CHIMNEY (RECEPTION HALL): This is a very large chimney and relatively easy to climb down. (Athletics DC 15).

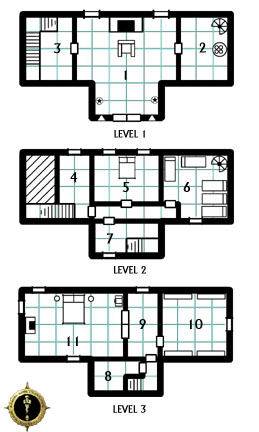

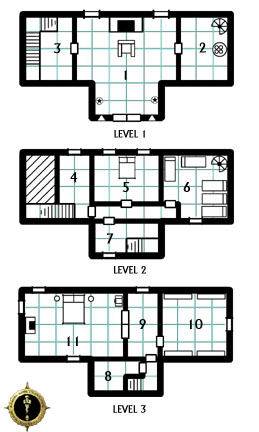

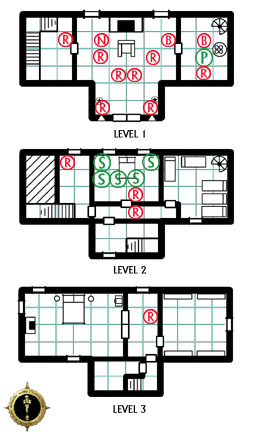

THE MANOR HOUSE – FIRST FLOOR

1. RECEPTION HALL: This is the hall in which Lord Padraig greets petitioners and sits in judgment.

The walls of this formal reception hall are paneled with dark mahogany polished to a gleaming shine. A high-backed wooden chair, its arms carved to look like bear claws and its back in sprigs of mistletoe, sits in a place of honor before a massive fire place.

The statues are of Lord Padraig’s father and grandfather.

2. KITCHEN:

An massive iron stove – an unmistakable remnant of the old Empire – fills the eastern wall of the kitchen. A spiral staircase of wrought iron stands in the corner, leading up to the second floor.

3. STAIRS:

Broad stairs of worn stone curve up to a landing on the second floor.

THE MANOR HOUSE – SECOND FLOOR

4. LANDING: There is a railing along the edge of this landing. It’s a 20 foot drop to the stone floor below.

5. GUEST BEDROOM: Lord Padraig offers this bedroom to visiting dignitaries. It is currently unoccupied. The bed is large and comfortable. There is an empty chest under the bed (where long-term guests can store their clothes and personal items).

6. SERVANT QUARTERS: Lord Padraig’s five servants sleep here.

Five narrow beds fill almost the entirety of this room. Although cramped, everything here appears to be kept in very neat order. There are footlockers beneath each of the beds.

The footlockers contain the possessions of the servants – mostly clothing and a few keepsake items. The footlockers are secured with very simple locks (Thievery DC 10). If the PCs choose to ransack them, there are a few items of value – a ring worth 15 gp; a golden lock with a portrait of a young woman worth 10 gp; a silver necklace worth 5 gp.

7. STAIRS: There is a portrait of Lord Padraig’s father hanging on the wall here.

THE MANOR HOUSE – THIRD FLOOR

8. STORAGE CLOSET: This closet contains a variety of common household goods – linens, lamp oil, mothballed clothing, a ladder, blank paper and ink, lanterns and lamps, and the like.

Tall shelves are crammed together in this narrow space, packed full with a wide effluvium of common household goods. There is a trapdoor in the ceiling, although it is partially blocked by one of the shelves.

The trapdoor leads up to the unused attic.

9. HALL: This grand hall leads to the library and lord’s bedchamber.

A thick, luxurious carpet runs the length of this hall. A chandelier of silver and glass hangs from the ceiling. Heavy doors of oak, carved with an Imperial signet of the old Empire, stand to one side with a smaller door to the other.

10. LIBRARY: This modest library offers a +2 bonus to History and Nature checks. Characters searching on particular topics of interest for the adventure may discover:

The True Historie of the Empire’s Keep, which describes the Keep on the Shadowfell (it gives the same information as a DC 25 Streetwise check and the first two paragraphs of Valthrun’s Follow-Up on the same topic).

Observations of Botany, a journal written by Lord Silvius (Lord Padraig’s great-grandfather). Silvius’ name is signed “Lord Silvius, Vassal of the Verdant Lord” and the text makes it clear that Silvius was a member of that druidic order. Near the end of the journal, Silvius mentions finding a cave which “led into what appear to be the ruins of the ancient keep”. He appeared to be fascinated by the unique cave ecology emerging there, but does not precisely give the location of the cave.

Four bookcases of blackoak stand along the walls of this library, their shelves covered in a wide variety of tomes and parchments.

11. LORD’S BEDCHAMBER: This is Lord Padraig’s bedchamber.

Upon the polished stone floor of this bedchamber sits an enormous bearskin rug at least twenty feet in length. A four-poster bed piled high with mattresses stands along one wall, an elegant fireplace is nestled along another. On one of the tables next to the bed there is a silver bust of a maiden’s head. A large chest of oak banded with steel sits in one corner.

CHEST: The chest is locked (Thievery DC 20). It mostly contains Lord Padraig’s clothing, but there is also a leather purse containing 100 gp in a random assortment of coin.

BEARSKIN RUG: Lord Padraig could tell the story of how his grandfather, Lord Patronus, led a hunting party to slay a dire bear that had been plaguing Winterhaven’s farms. The rug is worth 100 gp (although probably not in Winterhaven, where almost everyone would recognize it as belonging to Lord Padraig).

SILVER BUST: This bust is in the image of Padraig’s mother when she was a young woman. It is solid silver and would fetch a price of 225 gp (although probably not in Winterhaven, where almost everyone would recognize it as belonging to Lord Padraig).

THE MANOR HOUSE – ATTIC

A trap door in area 8 leads up to the fourth floor. The fourth floor was gutted decades ago by a fire and was later changed into an attic, which is now empty. There are, however, two windows in the south side.

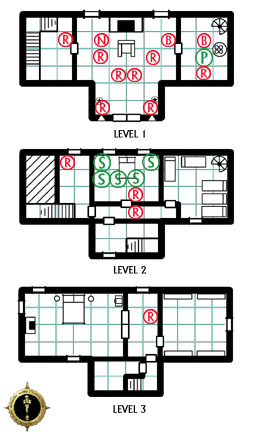

ENCOUNTER: THE MANOR SIEGE

CULTISTS:

CULTISTS:

Ninaran (KOTS pg. 61) (N)

Human Rabble (x12) (KOTS pg. 30) (R)

Human Berserker (x2) (MM pg. 163) (B)

HOSTAGES

Padraig (P)

Servants (x5) (S)

SITUATION: Ninaran and the cultists break into Padraig’s manor house and take him hostage. In the process, they kill four of the Winterhaven Regulars. Ninaran’s primary goal is to prevent the village from organizing any kind of resistance to Kalarel’s plans.

Padraig and his servants are kept securely bound with rope at the locations indicated on the encounter map.

ESCALATION: Ninaran starts by making an outrageous demand for ransom (25,000 gp). Then she’ll kill one of the servants and throw the body out the window. Next she’ll demand that 10 ritual sacrifices are performed in the courtyard before the manor house.

Ninaran doesn’t actually expect any of these demands to be met.

APPROACHING THE MANOR HOUSE: The only cultists actively keeping a lookout are the human rabble at the arrow slits on the first floor and at the northern window on the second floor. Approaching the manor house without being spotted requires a Stealth check (DC 10).

However, there are blind spots to the east and west. If PCs climb over the outer wall of Winterhaven and approach the manor house from due west or east, there is no chance they will be spotted.

TACTICS: The cultists on the upper levels are specifically there as lookouts. If they detect the presence of PCs, they will run downstairs and alert Ninaran. At that point, the cultists will take all the hostages down to area 1 and fortify themselves there.

Continued…

DOORS: The outer doors are barred from the inside (Break DC 20). The interior doors are not initially locked, although they can be if the cultists decide they need to barricade themselves (Break DC 16, Thievery DC 20).

DOORS: The outer doors are barred from the inside (Break DC 20). The interior doors are not initially locked, although they can be if the cultists decide they need to barricade themselves (Break DC 16, Thievery DC 20). CULTISTS:

CULTISTS: