Character Background: Tithenmamiwen

Today I’m posting the character background for the elven maid Tithenmamiwen, the second main character from In the Shadow of the Spire. I’m also continuing my discussion of the collaborative process of character creation.

STEP 1: THE PLAYER’S CONCEPT

Once the players know what the campaign concept is, I generally turn them loose to create whatever they want to create.

In some cases the strictures of the campaign concept will tightly curtail their options. For example, if the campaign is about a group of teenagers who have manifested psychic abilities and been drafted into a government secret-ops team… well, then I’m expecting to get back characters who are teenagers with psychic abilties.

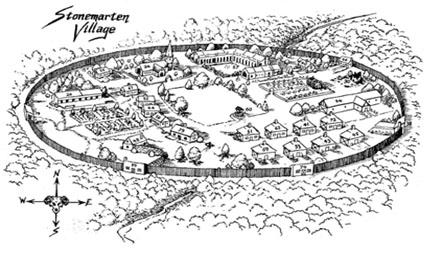

In the case of In the Shadow of the Spire, the players were pretty much given carte blanche with their character concepts. There were basically only two instructions: First, I wanted the characters to be newcomers to Ptolus. Second, I didn’t want the players to try to explain why they had come to Ptolus (that would be handled at the beginning of the campaign).

Once I get a character concept back from my players, the next step is integrating that concept into the campaign. There are actually two parts to this process, which I’ll refer to as public and private.

STEP 2: PUBLIC INTEGRATION

The public integration is a collaborative process where I try to work the character more deeply into the cultural and historical aspects of the campaign world. There are two reasons for doing this: First, I find that the collaboration tends to encourage more deeply imagined characters. Second, my players rarely know as much about the campaign setting as I do (even if it’s a published campaign setting). So this collaboration is both a way to take advantage of the deeply detailed settings I like to use and a way of introducing the player to the setting.

The actual process of collaboration will vary quite a bit.

In the case of Agnarr, for example, the player gave me a 1st-level barbarian and a very simple character concept: “A northern barbarian / fighter.” A nice, clear-cut archetype. I asked several qualifying questions, and eventually wrote up a complete character background (which also included the hook for the beginning of the campaign). Because the player was mostly interested in that clear-cut archetype, the final result just hints at some cultural content that could be used to play up that archetype.

In the case of Tithenmamiwen (Tee), on the other hand, the player had a very specific concept of the character as a young elf girl with dead-or-missing parents; a desire to find her own identity; a rebellious streak; and a deep desire to unravel secrets. The player was very interested in the cultural details I was giving her, and so the final character background was rich with those details.

In terms of process, there’s no right or wrong here. And it’s not about me, as the GM, trying to impose my concept of the character. Rather, I have two goals:

First, I want to realize the player’s character within the context of the game world. Basically, I try to assume a permissive stance. If the player comes to me with a concept, my primary goal is to find some way of making that concept work.

Second, I want to find ways to use the depth of the game world to enrich the character concept. This may sound complex or overtly literary, but it’s really just a matter of figuring out how to link the character into the world. In fact, you’re probably doing it already. When the player says, “I want to play the priest of a god of war.” You say, “The god of war is Itor.”

Of course, you can also make it more than that. You can add details about how the church of Itor operates; what the history of the church is; what the religious uniforms of the church are; what the holy symbol of the god is; and so forth.

I also like to take this integration process as an invitation to become creative myself. When a player comes to me wanting to play a knight, for example, I might take that opportunity to write up a couple of pages describing the philosophy of the Order of the Holy Sword.

One the flip-side, you shouldn’t think of this as a one-sided process. If the player wants to develop a knightly order for their character to belong to, I think it’s foolish not to take advantage of that creative work. (The collaboration now becomes a matter of how that knightly order can be integrated into the wider campaign world.)

Similarly, I always try to leave the final say with the player. (Because, again, it’s about developing their original character concept — not changing it.) For example, if they come to me with a knight and I send them back a couple pages describing the philosophy of the Order of the Holy Sword, I’ll try to make a point of asking, “Does that sound right?”

If it isn’t, we’ll try to figure out where I misinterpreted the character concept and try to find a solution that works. And maybe that means that they’re a member of some other knightly order.

STEP 3: PRIVATE INTEGRATION

For all intents and purposes, the character is now ready to go. But as a GM, I’m not finished. At this point, I’ll start figuring out how to hook the character into the larger structure of the campaign.

Is there a major villain in the second act? Make it the long-lost brother of one of the PCs.

Is there a kidnap victim in the third adventure? Make it the mentor of one of the PCs.

Was I planning to have a corrupt order of wizards? Give one of the PCs a chance to join it.

And so forth. It’s about figuring out how to make the campaign about the characters instead of just involving the characters.

STEP 4: MAKING THE PARTY

Technically this isn’t a separate step. It’s something that should be taken under consideration throughout the entire character creation process.

What binds these disparate characters together?

I like to consider myself as being fairly skilled at handling situations where the PCs split up, but even I don’t think it’s a good idea to run a campaign where the PCs don’t have some sort of cohesion.

D&D, again, has a traditional advantage in that it provides a baseline answer to that problem: We’re here for the loot. But it’s usually a good idea to figure out a better explanation for how the group came together and why they’ll stay together. Either providing a common, meaningful goal or having them all part of the same organization are usually the best way to accomplish that.

This is probably an opportune time to point out that the collaborative process of character creation doesn’t have to be limited to a conversation between the GM and the player — it can involve the entire table. It can often be a good idea to have a special session for character creation. It can allow for open discussion of what the game should be; who the characters should be; and how they’re interconnected. That didn’t happen as much with In the Shadow of the Spire because it was being run online, but it’s a valuable technique.