Four years ago, in an effort to understand why I found so many of the design decisions in the 4th Edition of Dungeons & Dragons antithetical to what I wanted from a roleplaying game, I wrote an essay about “Dissociated Mechanics”. At the time, I was still struggling to both define and come to grips with what that concept meant. I was also, simultaneously, quantifying and explaining my reaction to 4th Edition (which had just been released).

Ultimately, I hit on something that rang true. I had found the definition of something that was deeply problematic for a lot of people. The term “dissociated mechanic” caught on and became widely used. (And not just in discussions about 4th Edition.)

As a result, hundreds of people are linked to the original “Dissociated Mechanics” essay every month. They come looking for an explanation of what the term means.

Unfortunately, the original essay is not particularly good.

I say this both as a matter of self-reflection and as a matter of empirical evidence: The essay is unclear because I was still struggling to understand the term myself. And because it was written as a reaction to 4th Edition, it immediately alienates people with a personal stake in the edition wars. The result is that a lot of people come away from the essay with a confused, inadequate, or completely erroneous understanding of the term.

Which is why links to the original essay are being redirected here: I’m attempting to provide a better and clearer primer for those interested in understanding what dissociated mechanics are, why they’re deeply problematic for many people, and how they can be put to good use.

If you’re interested in reading the original essay, you can still find it here.

A SIMPLE DEFINITION

An associated mechanic is one which has a direct connection to the game world. A dissociated mechanic is one which is disconnected from the game world.

The easiest way to perceive the difference is to look at the player’s decision-making process when using the mechanic: If the player’s decision can be directly equated to a decision made by the character, then the mechanic is associated. If it cannot be directly equated, then it is dissociated.

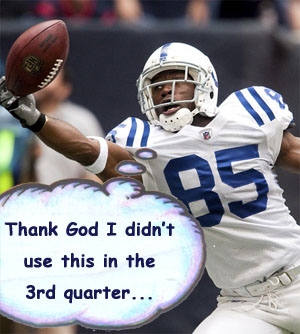

For example, consider a football game in which a character has the One-Handed Catch ability: Once per game they can make an amazing one-handed catch, granting them a +4 bonus to that catch attempt.

For example, consider a football game in which a character has the One-Handed Catch ability: Once per game they can make an amazing one-handed catch, granting them a +4 bonus to that catch attempt.

The mechanic is dissociated because the decision made by the player cannot be equated to a decision made by the character. No player, after making an amazing one-handed catch, thinks to themselves, “Wow! I won’t be able to do that again until the next game!” Nor do they think to themselves, “I better not try to catch this ball one-handed, because if I do I won’t be able to make any more one-handed catches today.”

On the other hand, when a player decides to cast a fireball spell that decision is directly equated to the character’s decision to cast a fireball. (The character, like the player, knows that they have only prepared a single fireball spell. So the decision to expend that limited resource – and the consequences for doing so – are understood by both character and player.)

METAGAMED AND ABSTRACTED

Dissociated mechanics can also be thought of as mechanics for which the characters have no functional explanations.

But this generalization can be misleading when taken too literally. All mechanics are both metagamed and abstracted: They exist outside of the character’s world and they are only rough approximations of that world.

For example, the destructive power of a fireball is defined by the number of d6’s you roll for damage; and the number of d6’s you roll is determined by the caster level of the wizard casting the spell.

If you asked a character about d6’s of damage or caster levels, they’d obviously have no idea what you were talking about. But the character could tell you what a fireball is and that casters of greater skill can create more intense flames during the casting of the spell.

The player understands the metagamed and abstracted mechanic (d6’s and caster levels), but that understanding is directly associated with the character’s understanding of the game world (burning flames and skilled casters).

EXPLAINING IT ALL AWAY

On a similar note, there is a misconception that a mechanic isn’t dissociated as long as you can explain what happened in the game world as a result.

The argument goes like this: “Although I’m using the One-Handed Catch ability, all the character knows is that they made a really great one-handed catch. The character isn’t confused by what happened, so it’s not dissociated.”

What the argument misses is that the dissociation already happened in the first sentence. The explanation you provide after the fact doesn’t remove it.

What the argument misses is that the dissociation already happened in the first sentence. The explanation you provide after the fact doesn’t remove it.

To put it another way: The One-Handed Catch ability is a mechanical manipulation with no corresponding reality in the game world whatsoever. You might have a very good improv session that is vaguely based on the dissociated mechanics you’re using, but there has been a fundamental disconnect between the game and the world. You could just as easily be playing a game of Chess while improvising a vaguely related story about a royal coup starring your character named Rook or narrating what your character sees on their walk from Park Place to Boardwalk.

REASSOCIATING THE MECHANIC

The flip side of the “explaining it all away” misconception is the “it’s easy to fix” fallacy. Instead of providing an improvised description that explains what the mechanic did after the fact, we instead rewrite the ability to provide an explanation and, thus, re-associate the dissociated mechanic.

In practice, this is frequently quite trivial. To take our One-Handed Catch ability, for example, we could easily say: The player activates his gravitic force gloves (which have a limited number of charges per day) to pull the ball to his hand. Or he shouts a prayer to the God of Football who’s willing to help him a limited number of times per day. Or he activates one of the arcane tattoos he had a voodoo doctor inscribe on his palms.

These all sound pretty awesome, but each of them carries unique consequences. If it’s gravitic force gloves, can they be stolen or the gravitic field canceled? Can he shout a prayer to the God of Football if someone drops a silence spell on him? If he’s using an arcane tattoo, does that mean that the opposing team’s linebacker can use a dispel magic spell to disrupt the catch?

(This is getting to be a weird football game.)

Whatever explanation you come up with will have a meaningful impact on how the ability is used in the game. And that means that each and every one of them is a house rule.

Why is this a problem?

First, there’s a matter of principle. Once we’ve accepted that you need to immediately house rule the One-Handed Catch ability, we’ve accepted that the game designers gave us a busted rule that needs to be fixed before it can be used. The Rule 0 Fallacy (“this rule isn’t broken because I can fix it”) is a poor defense of any game.

But there’s also a practical problem: While it may be easy to fix a single ability like One-Handed Catch, a game filled with such abilities will require hundreds (or thousands) of house rules that you now need to create, keep track of, and use consistently. What is trivial for any single ability becomes a huge problem in bulk.

REALISM vs. ASSOCIATION

Another common misunderstanding is to equate associated mechanics with realistic mechanics.

This seems to primarily arise because people struggling to explain why they don’t like dissociated mechanics – often without a firm conceptual grasp of what it is that they’re dissatisfied with – will try to explain, for example, that it’s just not realistic for a football player to only be able to make a single one-handed catch per game.

That may or may not be true (I haven’t actually done a statistical analysis of how often receivers make one-handed catches in the NFL), but it’s largely a red herring: Our hypothetical One-Handed Catch ability is infinitely more realistic than a fireball, and yet the latter is associated while the former is not.

Conversely, of course, just because something is magical doesn’t mean that the mechanic will automatically be associated. And it’s fully possible for a dissociated mechanic to also be unrealistic. My point is that the property of associated/dissociated is completely unrelated to the property of realistic/unrealistic.

WHAT IS A ROLEPLAYING GAME?

All of this is important, because roleplaying games are ultimately defined by mechanics which are associated with the game world.

Let me break that down: Roleplaying games are self-evidently about playing a role. Playing a role is making choices as if you were the character. Therefore, in order for a game to be a roleplaying game (and not just a game where you happen to play a role), the mechanics of the game have to be about making and resolving choices as if you were the character. If the mechanics of the game require you to make choices which aren’t associated to the choices made by the character, then the mechanics of the game aren’t about roleplaying and it’s not a roleplaying game.

To look at it from the opposite side, I’m going to make a provocative statement: When you are using dissociated mechanics you are not roleplaying. Which is not to say that you can’t roleplay while playing a game featuring dissociated mechanics, but simply to say that in the moment when you are using those mechanics you are not roleplaying.

I say this is a provocative statement because I’m sure it’s going to provoke strong responses. But, frankly, it just looks like common sense to me: If you are manipulating mechanics which are dissociated from your character – which have no meaning to your character – then you are not engaged in the process of playing a role. In that moment, you are doing something else. (It’s practically tautological.) You may be multi-tasking or rapidly switching back-and-forth between roleplaying and not-roleplaying. You may even be using the output from the dissociated mechanics to inform your roleplaying. But when you’re actually engaged in the task of using those dissociated mechanics you are not playing a role; you are not roleplaying.

I say this is a provocative statement because I’m sure it’s going to provoke strong responses. But, frankly, it just looks like common sense to me: If you are manipulating mechanics which are dissociated from your character – which have no meaning to your character – then you are not engaged in the process of playing a role. In that moment, you are doing something else. (It’s practically tautological.) You may be multi-tasking or rapidly switching back-and-forth between roleplaying and not-roleplaying. You may even be using the output from the dissociated mechanics to inform your roleplaying. But when you’re actually engaged in the task of using those dissociated mechanics you are not playing a role; you are not roleplaying.

And this brings us to the very heart of what defines a roleplaying game: What’s the difference between the boardgame Arkham Horror and the roleplaying game Call of Cthulhu? In Arkham Horror, after all, each player takes on the role of a specific character; those characters are defined mechanically; the characters have detailed backgrounds; and plenty of people have played sessions of Arkham Horror where people have talked extensively in character.

I pick Arkham Horror for this example because it exists right on the cusp between being an RPG and a not-RPG. So when people start roleplaying during the game (which they indisputably do when they start talking in character), it raises the provocative question: Does it become a roleplaying game in that moment?

I pick Arkham Horror for this example because it exists right on the cusp between being an RPG and a not-RPG. So when people start roleplaying during the game (which they indisputably do when they start talking in character), it raises the provocative question: Does it become a roleplaying game in that moment?

On the other hand, I’ve had the same sort of moment happen while playing Monopoly. For example, there was a game where somebody said, “I’m buying Boardwalk because I’m a shoe. And I like walking.” Goofy? Sure. Bizarre? Sure. Roleplaying? Yup.

Let me try to make this distinction clear: When we say “roleplaying game”, do we just mean “a game where roleplaying can happen”? If so, then I think the term “roleplaying game” becomes so ridiculously broad that it loses all meaning. (Since it includes everything from Monopoly to Super Mario Brothers.)

Rather, I think the term “roleplaying game” only becomes meaningful when there is a direct connection between the game and the roleplaying. When roleplaying is the game.

It’s very tempting to see all of this in a purely negative light: As if to say, “Dissociated mechanics get in the way of roleplaying and associated mechanics don’t.” But it’s actually more meaningful than that: The act of using an associated mechanic is the act of playing a role.

Because the mechanic for a fireball spell is associated with the game world, when you make the decision to cast a fireball spell you are making that decision as if you were your character. In making the mechanical decision you are required to roleplay (because that mechanical decision is directly associated to the character’s decision). You may not do it well. You’re not going to win a Tony Award for it. But in using the mechanics of a roleplaying game, you are inherently playing a role.

USING DISSOCIATED MECHANICS

Ultimately, this explains why so many people have had intensely negative reactions to dissociated mechanics: They’re antithetical to the defining characteristic of a roleplaying game and, thus, fundamentally incompatible with the primary reason many people play roleplaying games.

Does this mean that dissociated mechanics simply have no place in a roleplaying game?

Not exactly.

First, dissociated mechanics have always been part of roleplaying games. For example, character generation is almost always dissociated and that’s also true for virtually all character advancement systems, too. It’s also true for a lot of the mechanics that GMs use. (In other words, dissociated mechanics are frequently used – and accepted – in the parts of the game that aren’t about roleplaying your character.)

Second, people often have reasons for playing and enjoying roleplaying games which have nothing to do with playing a role: They might be playing for tactical challenges or to tell a great story or to vicariously enjoy their character doing awesome things. Mechanics that let those players scratch their itches can be great for them, even if it means they have to temporarily stop roleplaying in order to use them. Games don’t need to be rigid in their focus.

An extreme example of this are people who play roleplaying games as storytelling games: Their primary interest isn’t roleplaying at all; it’s the telling of a story. (In my experience, these players are often the ones who are most confused by other people having an extreme dislike for dissociated mechanics. After all, dissociated mechanics don’t interfere with their creative agenda at all. For a lengthier discussion of this issue, check out “Roleplaying Games vs. Storytelling Games”.)

In short, this essay should not be seen as an inherent vilification of dissociated mechanics. But I do think it important for game designers to understand what they’re giving up when they use dissociated mechanics; and to make sure that what they’re gaining in return is worth the price they’re paying.

For example, consider a football game in which a character has the One-Handed Catch ability: Once per game they can make an amazing one-handed catch, granting them a +4 bonus to that catch attempt.

For example, consider a football game in which a character has the One-Handed Catch ability: Once per game they can make an amazing one-handed catch, granting them a +4 bonus to that catch attempt.