Go to Part 1

I want to talk for a moment about my own personal history with D&D. I’ve previously described on this site how I first got into roleplaying games. I still remember walking into Pinnacle Games in Rochester, MN and seeing the five D&D boxed sets — the Basic, Expert, Companion, Master, and Immortal boxes — spread out rainbow-like along the top of a shelf. I spent months saving my allowance money in order to buy one boxed set after another, with each new purchase expanding the scope and depth of the game for me.

I want to talk for a moment about my own personal history with D&D. I’ve previously described on this site how I first got into roleplaying games. I still remember walking into Pinnacle Games in Rochester, MN and seeing the five D&D boxed sets — the Basic, Expert, Companion, Master, and Immortal boxes — spread out rainbow-like along the top of a shelf. I spent months saving my allowance money in order to buy one boxed set after another, with each new purchase expanding the scope and depth of the game for me.

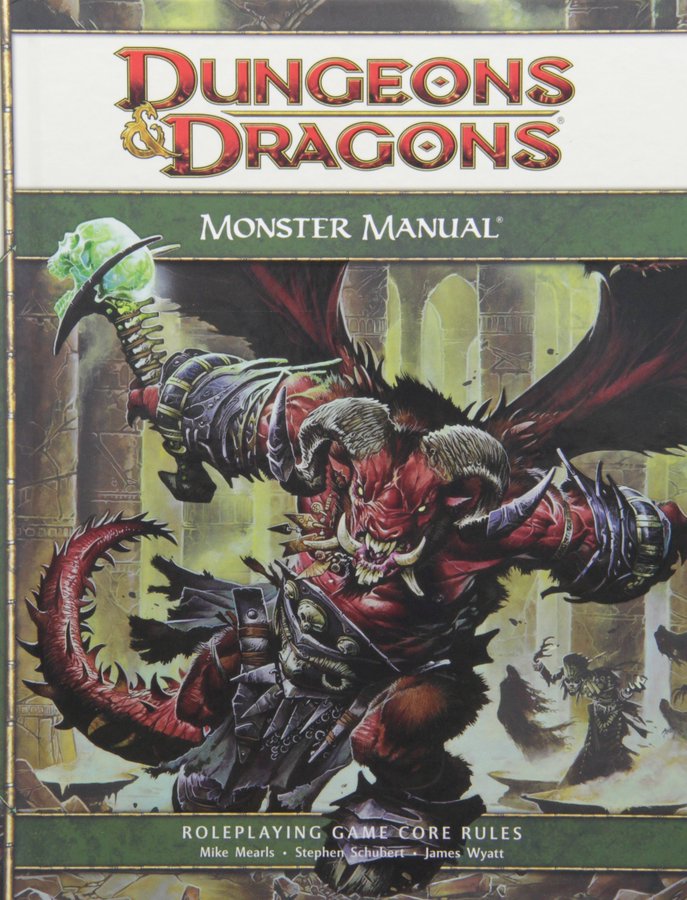

This was during the summer and fall of 1989, and it wasn’t long before I had picked up the AD&D 2nd Edition Player’s Handbook and Dungeon Master’s Guide. Then I picked up a used copy of the 1st Edition Monster Manual, which I used in conjunction with the 2nd Edition rulebooks for nearly half a decade until the hardcover Monstrous Manual was released in 1993.

During this half-decade span, I was playing with classmates and discussing the game in a variety of online forums, most notably the ADND FidoNet echo. I remember fondly people like Bruce Norman, John Givler, Bruce Norman, Alesia Chamness, Linda Rash, Alaeseus Starbreeze, David Bolack, Laurie Brown, Dr Pepper, and many others. It was here that I first encountered the concept of PBeM campaigns, and watching multiple games play out in slow motion across the echo helped shape my perceptions of what roleplaying games were capable of. When Bruce Norman got an adventure published in Dungeon Magazine, it inspired me to start submitting my own work. John Givler’s prodigious output of homebrewed items, spells, and monsters taught my kit-bashing by example.

(If anyone reading this has text archives from those days, I’d love to hear about it. Mine are fragmentary and incomplete.)

In short, I was young and I was excited by my hobby.

But there was also something else happening during this time period: A growing dissatisfaction with AD&D. Why were the core mechanics such an inconsistent and random jumble? Why couldn’t wizards wear armor (even if they weren’t casting spells)? Why was the alignment system so punitive? Why did demi-humans have level caps? Why was there both a multi-classing system and a dual-classing system that produced such blatantly unbalanced results? And so forth. (This really just scratches the surface.)

But there was also something else happening during this time period: A growing dissatisfaction with AD&D. Why were the core mechanics such an inconsistent and random jumble? Why couldn’t wizards wear armor (even if they weren’t casting spells)? Why was the alignment system so punitive? Why did demi-humans have level caps? Why was there both a multi-classing system and a dual-classing system that produced such blatantly unbalanced results? And so forth. (This really just scratches the surface.)

And like a lover who has become discontented with his mistress, the existence of so many faults quickly made other foibles and quirks intolerable. Classes instead of a skill system? Vancian spellcasting instead of spell points? Hit points instead of a wound system? Pshaw.

I was hardly alone. Everyone I knew who played AD&D — both online and offline — had campaigns chock full of house rules trying to fix the foibles of the game. In the end, I was playing a version of AD&D using a binder of house rules thicker than the core rulebooks. And eventually I grew sick of doing it. By the late ’90s, I had stopped playing the game entirely.

Then, in 1999, the development of 3rd Edition was announced. I was skeptical and cynical beyond belief. And when Ryan Dancey announced his plans for the Open Gaming License, I found the entire concept absurd: The busted, archaic, creaky mechanics of AD&D were going to take the roleplaying industry by storm? Why would anyone use those rules as a platform for development? I got involved in countless online debates, scoffing at the entire concept.

And then Ryan Dancey did something really audacious: In response to my relentless criticism and skepticism, he made me a playtester and sent me a playtest copy of the Player’s Handbook.

And then Ryan Dancey did something really audacious: In response to my relentless criticism and skepticism, he made me a playtester and sent me a playtest copy of the Player’s Handbook.

So I read through the playtest document and I sent Dancey a lengthy list of comments. And then I playtested the game and sent him another list of comments. In short, I did my job.

And Dancey had done his: By the time I finished reading through the playtest document, I was sold on 3rd Edition. What I was holding in my hands was essentially the game I had been trying to create with my binder full of house rules: A unified core mechanic. A skill system coupled to a flexible class system. Arbitrary prohibitions replaced with logical consequences. It even took away with the alignment strait-jacket.

It wasn’t the perfect game. But it felt like the Platonic Ideal of AD&D that all of us had been struggling to find through our incessant house ruling.

And here was the real trick of it: It still played like D&D. It still felt like that game I had fallen in love with back in the summer of ’89 when I first peeled the shrinkwrap off the Basic Set.

Let me take a moment and explain what I mean by that: Yes, THAC0 was gone. Yes, the XP tables had been mucked with. Yes, the saving throw categories had been streamlined. Yes, skills and feats had been added to the game. In fact, the list of changes — if you wanted to be sufficiently nitpicky with it — could be almost endless.

But here’s the rub of it: Playing a fighter still felt like playing a fighter. Playing a wizard still felt like playing a wizard. And so forth.

Playing D&D3 felt as much like playing AD&D as AD&D had felt like playing BECMI.

Which — at the end of this long, winding road of nostalgia — brings me to my point:

4th Edition doesn’t play like D&D.

4th Edition doesn’t play like D&D.

Some of the names are still the same, but playing a fighter doesn’t feel like playing a fighter and playing a wizard doesn’t feel like playing a wizard.

Is it still a paper ‘n pencil roleplaying game? Yes. Is it still about exploring dungeons and slaying dragons? Yes.

Does it play like D&D? No.

The gameplay has been fundamentally altered. In similar fashion, both Chess and Stratego are boardgames featuring a highly abstract presentation of war played out on a grid. But Stratego isn’t the same game as Chess… even if you package it in a box with the word CHESS written across it in big, bold letters.

Sure, 4th Edition has the Dungeons & Dragons trademark splashed across its covers. But it isn’t the same game — any more than Rolemaster or Earthdawn or Exalted (all fantasy roleplaying games) are the same game. Or would become the same game just because you slapped the same name on the cover. New Coke may have had the Coke trademarks on its can, but that didn’t make it the same soda.

It should be noted that this isn’t to be taken as indictment of 4th Edition. There’s absolutely nothing about being “not D&D” that necessarily makes it a bad game. There are plenty of great RPGs which aren’t D&D, and Stratego is a fun game even if it isn’t Chess.

But the fact that 4th Edition isn’t the same game I’ve been playing for nearly two decades does play a significant role in why I won’t be making the switch to 4th Edition.

Back in 2002, Ron Edwards coined the term “fantasy heartbreaker”. He used it to refer to all of those games which are the result of their creators believing that they’ve taken the mousetrap (i.e. D&D) and made it a little bit better. In some cases they may be right and in some cases they may be wrong but, as Edwards pointed out, they were all doomed to failure. Why? Well, here Edwards goes off into an ideological rant that I think rather misses the point. But, in my opinion, the primary reason can be boiled down to this:

If I wanted to be play a game like this, I might as well be playing D&D.

There are many reasons for that sentiment to hold true, but I think there are two major ones:

(1) It’s much easier to find a group playing D&D than it is to find a group playing any other RPG.

(2) Most roleplaying gamers are already familiar with D&D — they’ve already learned the game.

So why would you go to the effort of learning a new game and then convincing other people to learn a new game in order to achieve an experience that you can already largely accomplish with a game you know and for which it’s easy to find experienced players?

Now, to be clear: 4th Edition will not be a fantasy heartbreaker. It’s got the Dungeons & Dragons trademark, tons of marketing muscle, and plenty of people who were either dissatisfied with 3rd Edition or just like anything shiny and new. From a commercial standpoint, it’s going to be a huge success by the standards of the industry. (The only open question is (a) whether it will be as large of a success as it could have been if it had taken a different route and (b) whether it will be a success by WotC’s standards.)

But for me, personally, I look on 4th Edition in much the same way that I’ve looked at the many fantasy heartbreakers I’ve read and played over the years. Only moreso. The game I love is not to be found here, and the game that has replaced it beneath the same shiny trademark is (a) intentionally designed to be inferior at doing all of the things that I enjoy doing with D&D and (b) sloppily designed in some fairly fundamental ways. And even if that wasn’t true, 4th Edition has failed to offer any substantive improvements or innovations that would justify abandoning my existing mastery of 3rd Edition in order to learn a fundamentally different game (which is, nevertheless, attempting to scratch the same itch).

D&D is dead. Long live 4th Edition.

But not for me.